On a normal day, Natalie Toth would be zipping around the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. As the institution's chief fossil preparator, she'd oversee volunteers and interns, help remove precious history from dirt casements and be pulled into collections vaults and offices on every floor of the massive space. But there hasn't been a normal day in weeks.

Instead, Toth's kitchen has become a prep lab. The table is covered with bundles of plaster containing the remains of millennia-old organisms. Bits of ancient crocodiles and a turtle shell lay not far from a coffeemaker and a sink full of dishes. She carves away at the sediment as Riley, her big black lab, sleeps at her feet.

"This is the longest we've ever been away, and it's really, really weird," she said. She's not just missing her colleagues: "I'm used to having more powerful and advanced tools."

The coronavirus work-from-home orders have slowed some of DMNS' scientific research. All of their field work, for instance, has been postponed until the fall. It worries Toth a bit, since fossils that have recently been uncovered are now exposed to the elements and must wait to find safe haven at the museum.

But the virus has not kept Toth and her colleagues from making big discoveries and announcements. On Wednesday, the DMNS announced a "blockbuster discovery" from their work in Madagascar.

It's called Adalatherium, which translates from the Malagasy and Greek languages as "crazy beast." It dates back about 66 million years and walked with dinosaurs. The museum calls it a "bizarre opossum-sized mammal." When scientists recreated what it might look like, alive and covered in fur, an artist rendered it black with white stripes. It looks skunk-like.

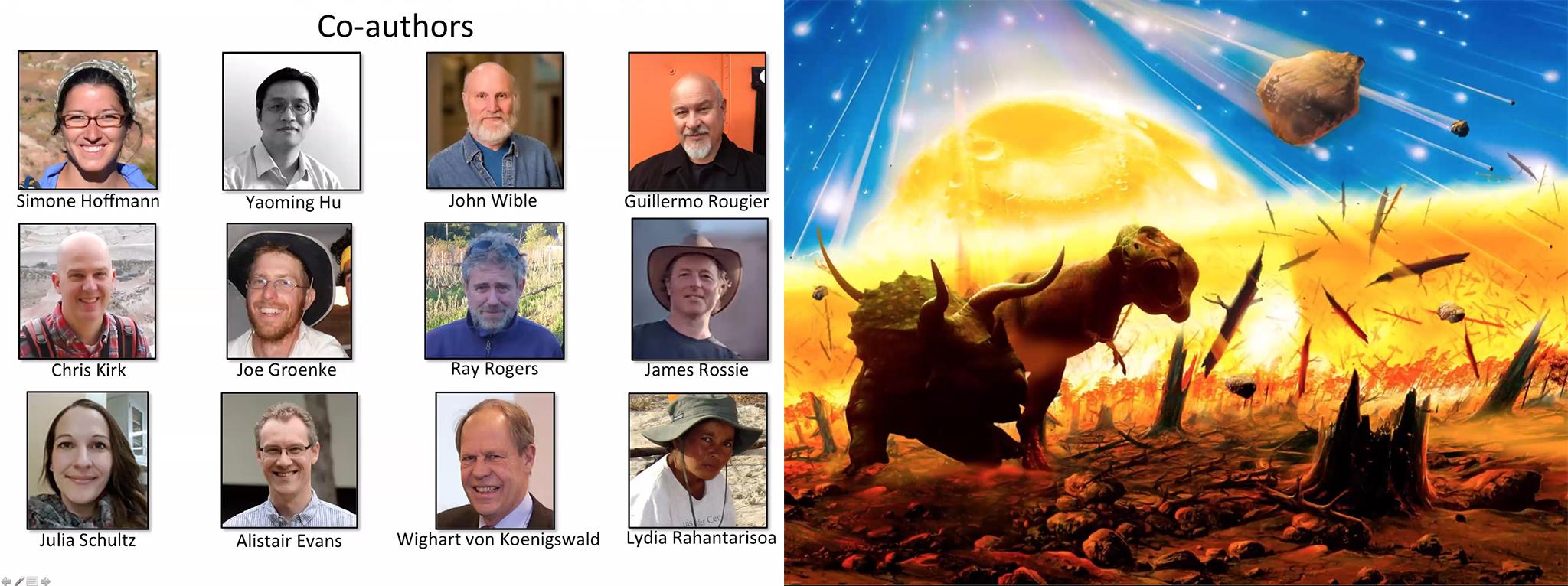

DMNS' senior curator of vertebrate paleontology, David Krause, who led the research team, said the "crazy" and "bizarre" descriptors are appropriate because Adalatherium features anatomy exhibited by no other mammal, living or extinct. It's as if its teeth are "from outer space," he said. In its skull above its snout, the team found a large hole for a physiologic purpose they can't figure out. It appears to have dug holes with its back feet, which is not a thing mammals usually do.

But the fossil's quality is also very rare. Toth said the team found Adalatherium hidden beneath fragments of reptiles that were written off at first. It wasn't until the team scanned a chunk of dirt a little deeper that it discovered the crazy beast preserved in its entirety.

"Every single bone in this animal's body is present," she said.

So, yes, paleontologic history is still being announced in the time of social isolation. But Toth said it's being discovered, too.

Although the digging has largely stopped for now, she said scientists like her who are stuck at home have more time than ever to dive deep into their data. The result, she expects, will be a surge of published papers.

"There's going to be some really cool discoveries," she said. "It's almost overwhelming."

She and her colleague Salvador Bastien are looking into some armored dinosaurs found in the American West that may either be unidentified variants of a known species or something new altogether.

This extra time at home, Toth said, has given her the space to think hard in one direction. It can be hard to focus so singularly when she'd otherwise be pulled all over the museum on a normal day. Besides, she said, so much of her job is about physically removing artifacts from Earth.

"I get to use the science part of my brain instead of the mud and the glue part of my brain," she said, adding that she's enjoying it.

Krause, who led the Madagascar expedition, said he's taking advantage of the quiet time, too. In the last couple of decades, he and his colleagues have begun CT scanning fossils to store multi-dimensional models on their computers. It means he can take his work anywhere, so social distancing hasn't stopped his progress.

"It hasn't slowed us down," he said. "It actually has allowed more time to focus."