Stay-at-home orders have drastically changed people's travel habits. And it turns out that when fewer people drive, fewer people crash, and fewer people die.

Traffic crashes are down 30 percent, according to Denver Police Department data. At 17 people killed while traveling around the city, Denver is on pace for 42 traffic deaths this year, which would be the lowest total since 2012.

"I think this is interesting information that tells us one of the big contributors to traffic fatalities is the number of cars on our street," said Jill Locantore, executive director of the Denver Streets Partnership, which advocates for safer roads. "And so to the extent that we can really encourage people to shift from driving to using other ways of getting around like walking, biking and transit, that is going to go a long way towards helping us achieve our Vision Zero goals."

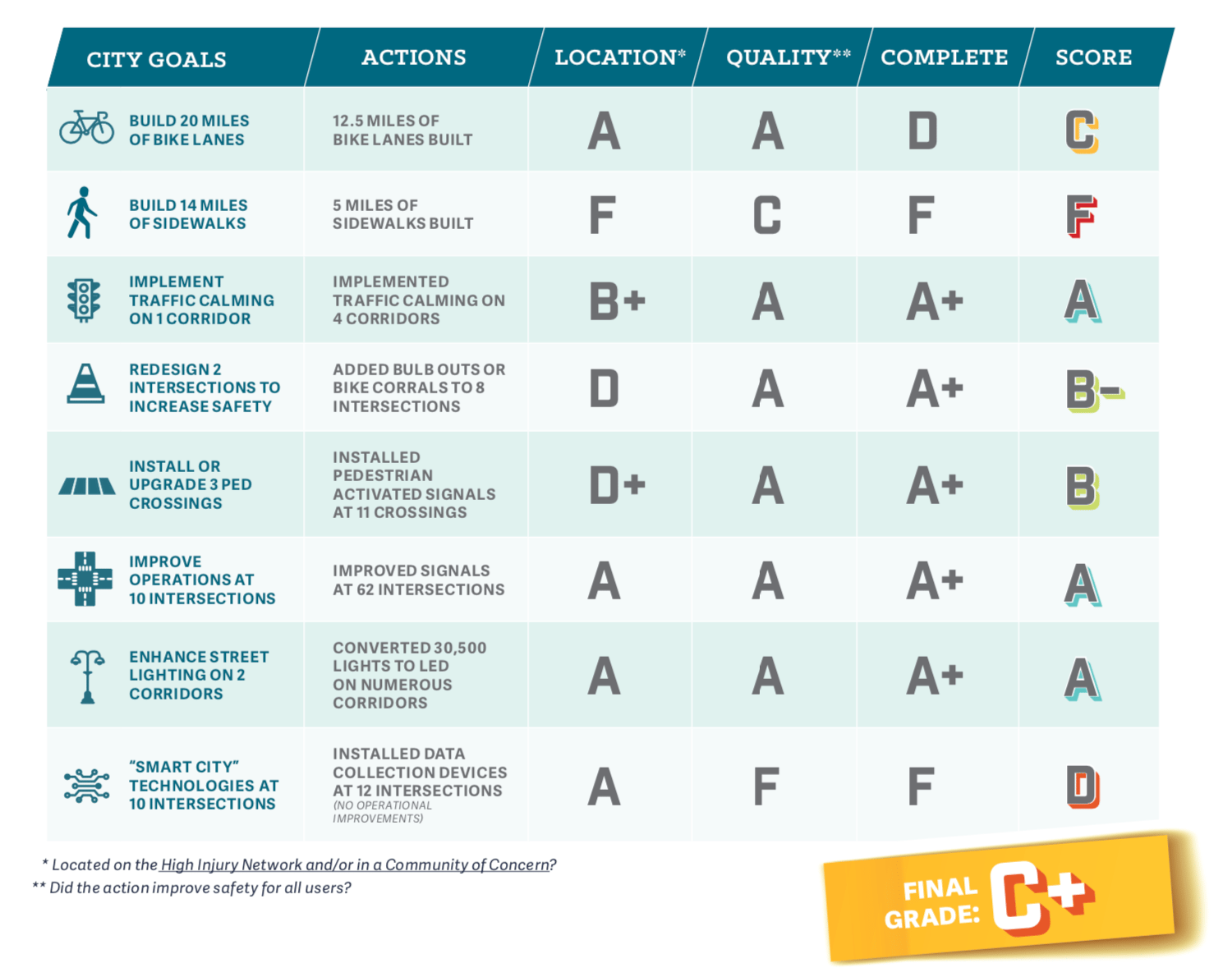

On Thursday the group released its "Vision Zero Report Card" aimed at holding the transportation department accountable for Mayor Michael Hancock's commitment to end traffic deaths under the banner of Vision Zero. In it, the Partnership compares the administration's promises for streets that prioritize walking, rolling, biking and transit with what was actually implemented in 2019.

Overall, the city received a C+.

On sidewalks, the street safety advocates gave the city government an F for building just five miles worth of walkways last year compared to a goal of 12 miles. Denver received a C for bike lanes after the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure installed 12.5 of the 20 miles intended.

Denver received high marks for making intersections safer and improving streetlights citywide as well as calming traffic with new street designs on 35th Avenue in northwest Denver where crews installed traffic circles and diverters to slow driving speeds and detour drivers.

DOTI refused to grant an interview with transportation director Eulois Cleckley or any staff member associated with the Vision Zero program. But spokeswoman Heather Burke provided documents outlining the department's 2019 and 2020 projects, including intersection improvements for people walking and in wheelchairs that run the length of East Colfax Avenue.

In an interview with Denverite earlier this year, Cleckley said his department is focused on redesigning streets and intersections to prevent crashes. He also said physical changes to roads are not enough.

"Street design is critical, but human behavior is just as critical, and we just need people to slow down and people to be aware of their surroundings," Cleckley said.

But Charlie Myers, who often bikes 35th Avenue with his kids, said the traffic circles and diverters installed on the street are obviously deterring car traffic and speeding, which Denver's government calls the "fundamental factor in crash severity."

"I've been bicycling the 35th (Avenue) neighborhood for years now, so I know what it was like before all these wonderful changes," Myers said. "It was a very harrowing experience to come up to Irving Irving Street there, especially during rush hour. You had cars going right, left and straight. And the cyclists were in the mix of this kind of harrowing, very daunting experience."

The Denver Streets Partnership made six demands to accompany its report card:

- Lower the default speed limit on residential streets from 25 to 20 mph

- Ban turns on red downtown and on the city's most dangerous streets

- Increase fines for parking in bike lanes

- Eliminate beg-buttons -- those buttons pedestrians have to press to cross some streets -- to make a pedestrian signal automatic

- "Aggressively" pursue changes to state law to allow red-light cameras on state-owned streets like Federal Boulevard

- Fully fund street safety projects. At current funding levels, the city's buildout will take four centuries, advocates said.

"We know that these things can reduce traffic injuries and fatalities and change people's behavior," said Molly McKinley, vice chair of the Denver Streets Partnership.

Denver's government is facing a $226 million shortfall and city departments, including the transportation division, are being asked to cut their budgets by 7.5 percent, potentially making Vision Zero funding harder to come by. But many projects are being paid for with dollars from a 2017 voter-approved bond, Locantore said.

"Vision Zero is critical to our mission, so we will continue to prioritize safety initiatives," said DOTI spokeswoman Nancy Kuhn. "We're also actively seeking grants and to leverage partnerships to advance our work."

This article originally misattributed a quote by Charlie Myers to David Chen and has been corrected.