As recently as late April, Denver Mayor Michael Hancock reiterated that he saw no need for a sanctioned camp for people experiencing homelessness.

But on Wednesday, he said the idea was being considered.

"We're looking at all the options right now," the mayor said during an update on his administration's response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

He said the city was studying "where in the nation and other places have these sanctioned camp sites worked, as well as how that might work if we were to have it here in Denver."

In Portland and San Francisco, the coronavirus crisis has reversed long-held opposition to sanctioned camping.

Hancock has said the priority should be getting people indoors. Since the pandemic reached Denver, his administration has worked with service providers to open shelters at the National Western Complex and at the nearby Coliseum that together can house some 1,000 people. The shelters are open 24 hours, which had been rare in Denver before the pandemic.

The city also has secured hotel rooms for people experiencing homelessness who need to recover from illness and for those considered most vulnerable to COVID-19.

Advocates of sanctioned camps say they are needed in part as a matter of fairness. Advocates point out that only people who go to shelters have been offered services such as COVID-19 testing and opportunities to get into one of the COVID-19 hotel rooms.

The Interfaith Alliance of Colorado and Colorado Village Collaborative presented a detailed plan developed with the architecture and urban design nonprofit Radian for what they call "temporary safe outdoor space" to top Hancock aides in late April. It did not specify a site. At the time, Kathleen Van Voorhis of the Interfaith Alliance said in a statement that "the safest, most reasonable approach during this public health emergency is to provide necessary resources to our neighbors on the streets by establishing a safe outdoor space where those continuing to live outside can maintain appropriate social distancing, engage with outreach coordinators, and have access to hand washing and health care services."

Denver voters last May overwhelmingly backed keeping a ban on urban camping imposed by City Council in 2012. Months after the vote, a Denver county judge ruled the camping ban unconstitutional. The city has appealed the judge's ruling, and a higher court decision is pending.

In April, eight members of Denver's 13-member City Council signed a letter to Hancock in support of the sanctioned camping proposal put forward by the Interfaith Alliance of Colorado and Colorado Village Collaborative. The city legislators said the proposal could help reduce "the risk of spread of the (coronavirus) among those who remain outdoors for a variety of reasons, including couples who are still unable to access our improved 24/7 shelters."

The eight council members who signed were Candi CdeBaca, Stacie Gilmore, Chris Hinds, Paul Kashmann, Robin Kniech, Debbie Ortega, Amanda Sandoval and Jamie Torres. Six members of the state legislature also signed the letter: Sen. Julie Gonzales, Rep. Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez, Rep. Susan Lontine, Sen. Robert Rodriguez, Rep. Emily Sirota and Rep. Steven Woodrow.

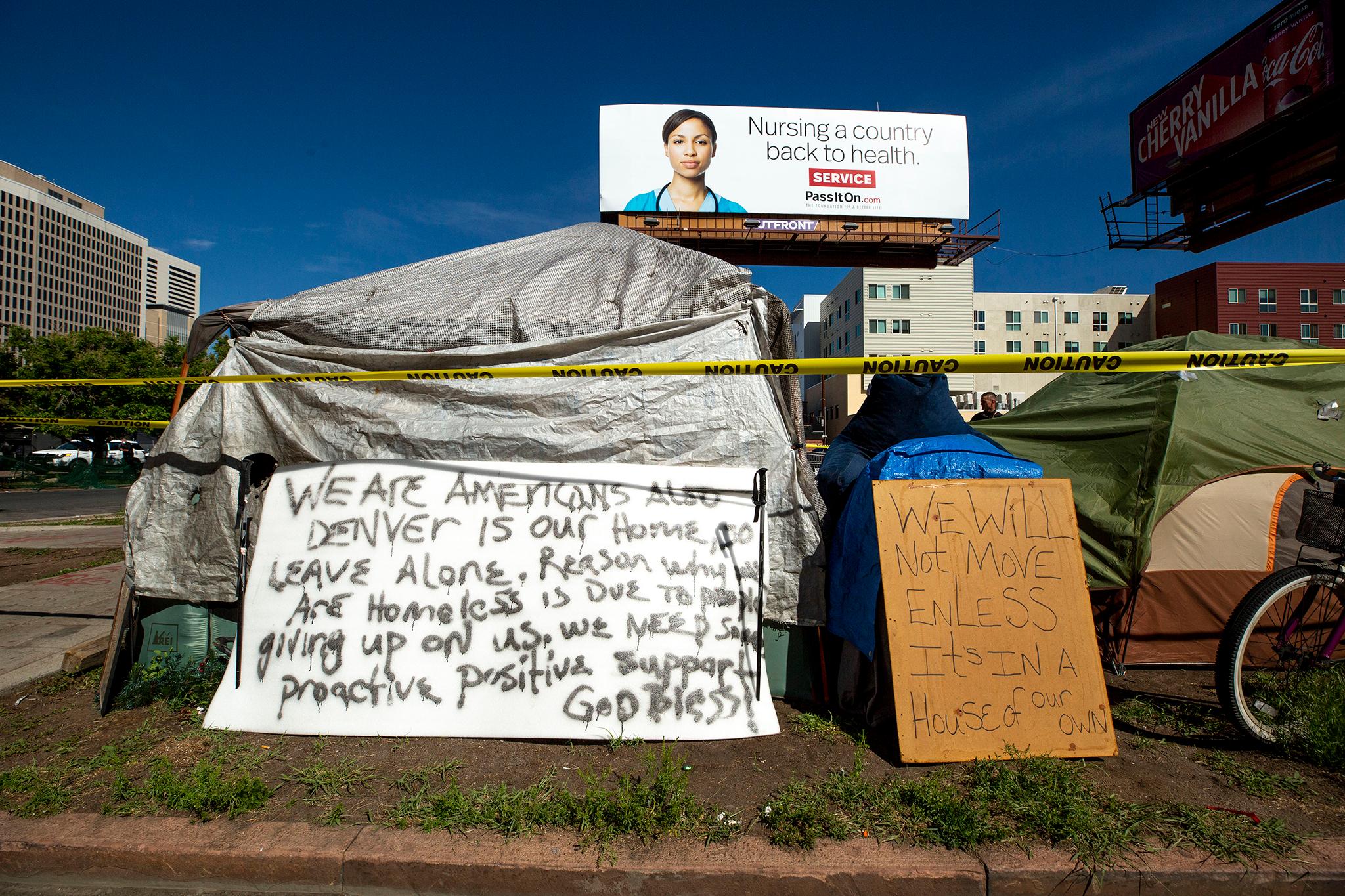

Hancock was asked during Wednesday's briefing about cleanups that disrupt people living on the streets at a time when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has cautioned that clearing encampments can increase the risk of spreading disease during the coronavirus outbreak by causing "people to disperse throughout the community and break connections with service providers."

Hancock said the city must weigh the risk posed by coronavirus against the public health threat posed by trash, needles and human waste that have been cleared from encampments.

"Some of these encampments have quite frankly spiraled into acute public health threats," Hancock said, adding that camps that do not pose health threats have been left alone.

Officials from the department of health who have led the cleanups have said that they they are necessary because of health threats and that people are asked to move only until the areas are made safe. But people experiencing homelessness have returned to find fencing and rocks that keep them from erecting tents. Some people have said that to avoid being repeatedly asked to move, they were seeking new encampments further from day shelters, portable toilets and other facilities that can be found in Five Points.