As an energized public and elected officials target the Denver Police Department for reform, DPD's union is negotiating new terms of employment, including how much officers get paid.

Most city government departments lack the power to collectively bargain for things like higher pay, better benefits and vacation. But DPD can, and its power to do so is enshrined in the city charter. Why? Police officers are not allowed to strike, so their ability to bargain essentially gives them a different kind of ammo.

The negotiations for a new contract -- the current one expires at the end of 2020 -- began behind closed doors on June 30 amid calls to de-fund and/or reform policing in the wake of George Floyd and other Black Americans being killed by law enforcement.

In Denver, collective bargaining agreements can be arenas for certain changes, but some are illegal to discuss. According to some policymakers, that's a good thing, because it leaves unions out of certain decisions and instead lets elected officials and their representatives guide the police department.

Details about the new police contract are not yet public. Here's what we know.

Some people get a seat at the table. The public does not.

Taxpayers, who pay for cops' bad behavior and for wage increases typically given to police officers after negotiations, are not allowed to sit in on the discussions. Gabriel Lavine, a leader in the Afro Liberation Front, said the meetings should be open. His group is one of many demanding changes to the police department, including the redirection of spending from patrol officers to things like mental health interventions and housing the unhoused.

"Reexamining the flexibility of law enforcement agencies and the input of their unions is the first step in holding them accountable," Lavine said. "The lack of transparency regarding these talks are indicative of a government that has no intention of understanding what we mean when we say things like 'de-fund the police.'"

Members of Denver's police union, the local chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police, and paid negotiators are representing officers according to the City Attorney's Office. Union leader Nick Rogers did not return calls for comment for this story.

Also typically at the table, according to the City Attorney's Office: a government lawyer who leads negotiations for the city, at least one rep from Mayor Michael Hancock's office, a high-ranking DPD official, someone from the Department of Safety, budget experts and people from the human resources department.

Denver City Council members will ultimately be tasked with approving the new contract, but they aren't in the negotiating room. The elected body's legislative director, Linda Jamison, an un-elected staffer, is listening to negotiations on their behalf -- but she apparently wasn't invited until three weeks into the process.

"I received no notice but reached out to the lead negotiator to see if the collective bargaining process had begun," Jamison wrote in an email to Lisa Calderón, City Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca's chief of staff, on Tuesday.

According to the city charter, "it is the obligation of the bargaining agent to serve written notice of request for bargaining on" the mayor and city council "or their representatives."

"All of the other workers in the city who aren't allowed to collectively bargain are having cuts forced upon them, where police are not," CdeBaca told Denverite. "And so I want to be listening to what's happening and how this is happening. And I have the right to be there. We have the right as a council to be represented there."

Council members are allowed at negotiations, according to the City Attorney's Office, but their involvement is not common.

According to the city charter, the mayor and the city council or their proxies must meet with the police union and bargain "in good faith." CdeBaca says that ship sailed.

Some things, like pay, must be discussed. But other big subjects are off-limits -- including a less powerful police department, officer discipline and DPD's budget.

Speech is not totally free inside the negotiating room. Denver's charter lays out three types of allowable conversations: stuff that must be discussed, stuff that can be discussed, and stuff that cannot be discussed.

Source: City and County of Denver collective bargaining contract.

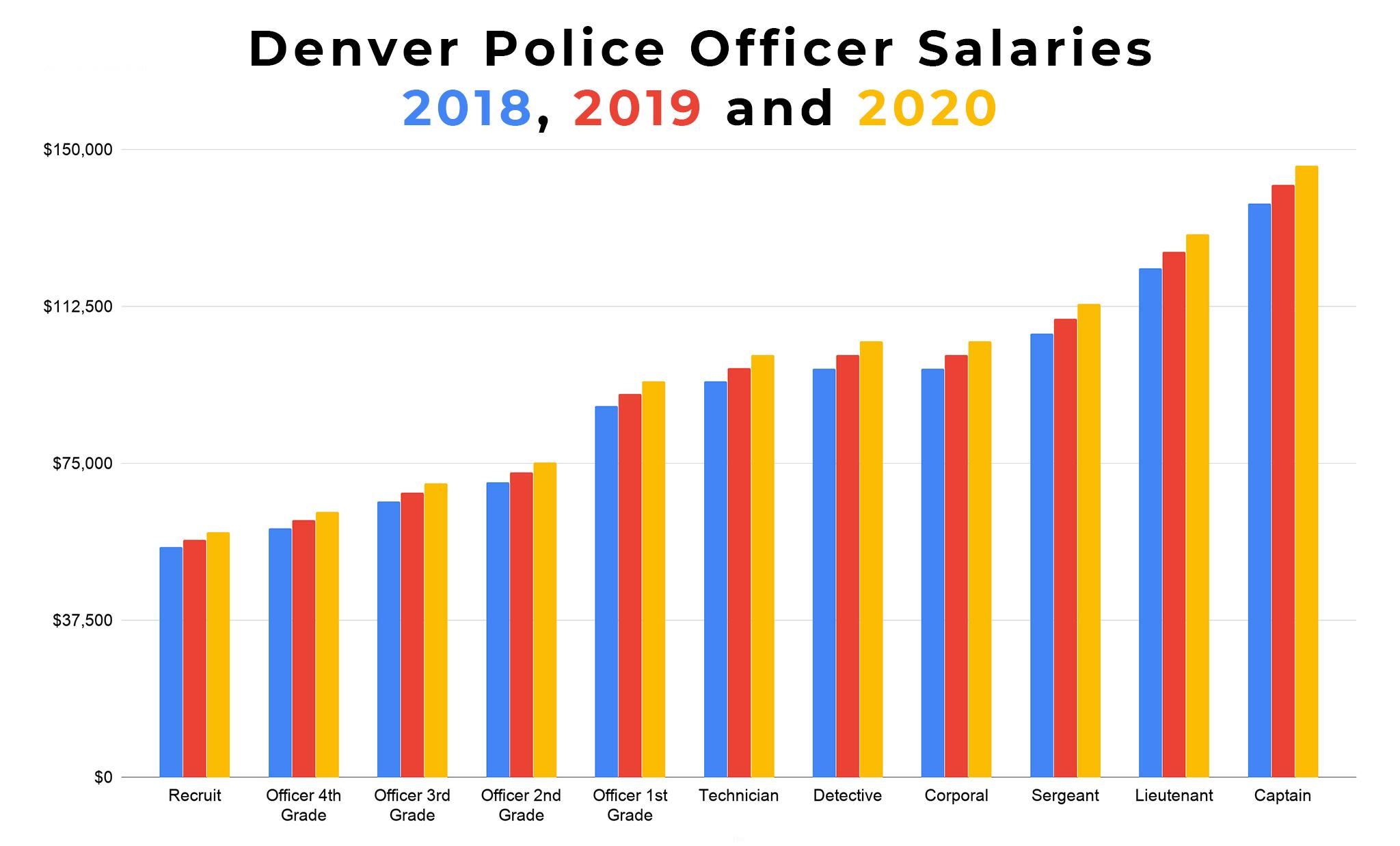

As calls for cuts to police funding continue, wages and benefits, including overtime pay and vacation, are required topics of conversation. The last contract between DPD and the city resulted in consecutive pay raises for officers, but it's unclear if that will happen in the next contract given the massive budget gap Denver must close. Worth noting: While most city government workers must take eight days off without pay this year, DPD's current contract with the city exempts police officers from furloughs.

Other required topics of discussion include the length of the agreement (the last one lasted three years), personal safety equipment and the number of hours in a work week.

Executive Director of Safety Murphy Robinson has committed to police reforms. But it's unclear if the collective bargaining agreement will be a venue for them, because 15 topics are off-limits during those conversations, according to the city charter. And many of them fall under things that criminal justice reform advocates would like to see changed.

For example, negotiators cannot legally discuss the "civilianization" of the police force, otherwise known as weakening its authority. Negotiators can't discuss DPD's budget, service standards, staffing levels, and how the department investigates, disciplines and trains its officers.

City Councilwoman Robin Kniech believes those limits are good because, unlike in some other cities, Denver's policymakers can make decisions about those things without having to negotiate with unions.

"In Denver, safety unions do lobby against some policy changes whether at the department level or (at) Council," said City Councilwoman Robin Kniech, who is also a lawyer, in an email. "But they've not stopped any at the Council level during my time. And they don't have the power to collectively bargain over many of the topics related to reform/accountability/transformation."

Councilwoman CdeBaca said that at least one big idea can be addressed in this collective bargaining agreement. When police officers mess up and the government has to compensate victims for their mistakes, she wants to see the burden shift from taxpayers to the police union. (A new state law allows officers to be sued but limits their personal liability at $25,000.) CdeBaca imagines some kind of insurance fund that officers pay into.

"It would be under permissive subjects to talk about," she said. "And I don't trust that the (Hancock) administration is bringing up or pushing the conversation around permissive subjects and shifting the liability of lawsuits onto the union."

Negotiations will last 45 days. If an agreement is reached, it will head to the city council for a vote. If not, it could go to arbitration.

This story has been updated to clarify the power the city and Department of Safety have over police department decisions.