The artist first asked for a moment of silence.

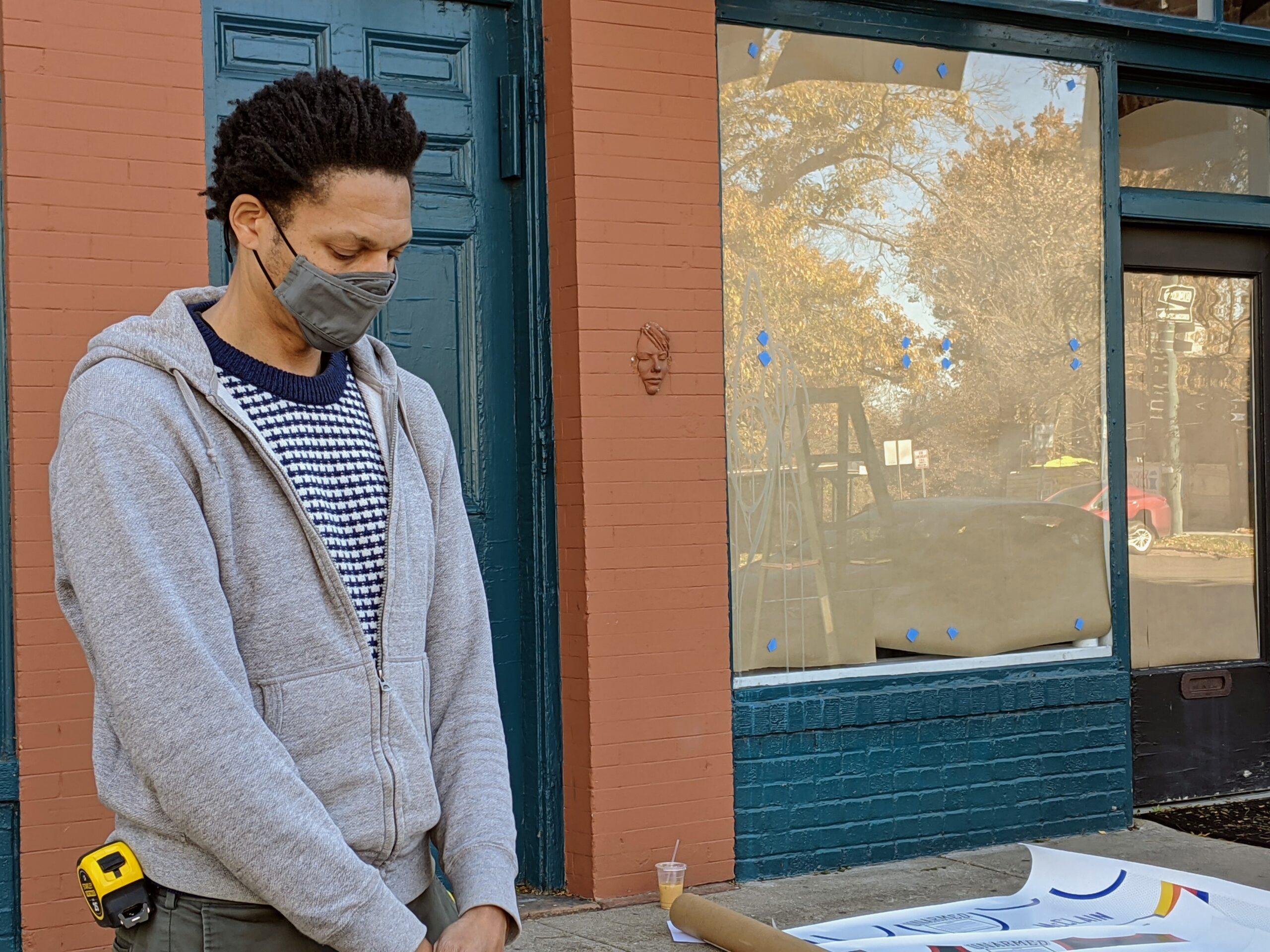

Then, on Día de los Muertos, Raafi Rivero placed four of his memorials to African-American victims of law enforcement violence on the windows of Leon Gallery in City Park West. Over the last seven years, the Brooklyn artist's quest to both honor the dead and urge the living to take action has evolved from social media posts, to images pasted graffiti-style on boarded up storefronts, to a display at an art gallery.

The project Rivero calls "Unarmed" was inspired in 2013 on the weekend a Florida jury announced it had found George Zimmerman not guilty in the death the year before of Trayvon Martin. Zimmerman, who told police he was concerned about burglaries in his neighborhood, had followed the unarmed Black 17-year-old, who had no criminal record. A fight ensued that rainy night. The jurors agreed that Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch volunteer, could have been justified in shooting because he feared great bodily harm or death.

In an artist statement, Rivero, who is Black, said photos of Martin reminded him of himself at the same age.

"It was around that time in life when the outside world started treating me differently. Like a threat," he writes.

Rivero saw "Fruitvale Station" the same July 2013 weekend that the Zimmerman verdict was announced. The film has been celebrated for its nuanced portrayal of Oscar Grant, an unarmed 22-year-old Black man shot in the back and killed by a police officer at a BART station in Oakland, Calif., in 2009. Rivero said he cried watching "Fruitvale Station" and knows many other Black men who had similar reactions.

"The following week, the whole week , I was thinking, 'What can I do as an artist to talk about police brutality?"' Rivero said. He is a filmmaker, but he decided not to emulate Ryan Coogler, the Black director of "Fruitvale Station" (and later "Black Panther").

A movie can take years to make. Rivero wanted to have an immediate impact. He turned to another of his skills, graphic design. He created images of basketball jerseys bearing the names of people such as Martin and Grant, their ages, and, instead of a team name, the word "unarmed." After sharing the first jerseys on social media, Rivero this summer began printing them as vinyl stickers that would be large enough to wear if they were clothing. He installed them on boarded storefronts in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Their slick, mass-produced quality and the uniformity evoke the numbing frequency of racist violence in the United States.

"At some point, I thought, 'I may have to do this for the rest of my life,'" Rivero said. "That part of the project is like a Sisyphean task. You want every jersey to be the last one. But you kind of know, intrinsically, that something's going to happen again."

Rivero has completed 14 "Unarmed" jerseys so far, each with sometimes subtle touches to answer questions he considers, such as, who is this person, what's their story, what do I want to highlight?"

The Leon windows have just enough room for four vinyl jerseys, which will be displayed until Saturday.

One is in the purple and gold of Texas's Prairie View A&M University, the alma mater of Sandra Bland. Bland, 28, was to start working at Prairie View in 2015, when a Texas state trooper stopped her for failing to properly signal a lane change. The trooper drew his stun gun and told Bland that "I will light you up" as he ordered her from her car. Bland was arrested on allegations of assaulting a public servant. Three days later she was found hanged in a Waller County Jail cell. Her death was ruled a suicide.

Rivero takes artistic license with Eric Garner's jersey, choosing blue and white stripes to evoke baseball's New York Yankees instead of a basketball team. Garner, 43, died in 2014 after New York officers confronted him about illegally selling cigarettes. One of the officers locked Garner in a chokehold. In a cellphone video, Garner can be heard saying "I can't breathe," words Rivero printed on the jersey.

A third jersey in the Leon window has the words "Big Floyd" over the heart. George Floyd, 46, died under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer this year.

At first glance, the fourth jersey in the windows looks like a Nuggets uniform. Instead of the Nuggets' six stripes across the chest, Rivero's Elijah McClain jersey has four, because a violin has four strings. McClain, 23, was a violinist who died in a Denver suburb. After McClain was violently detained by Aurora police, paramedics arrived and administered a large dose of ketamine to sedate him. McClain died in the hospital last August.

With each jersey, Rivero said, "I'm keeping this person's story alive, protesting injustice. I'm enabling the message of protest."

Sports are "a way to lead into a discussion around social justice without hitting you over the head with it," he said. "Racism is the activating force in these cases. I'm fighting against racism."

Rivero played soccer, baseball and basketball when he was younger. He also was a good student, and said he thought of himself as "this all-American kid." He suspects the parents of his white teammates didn't see him as a leader.

"I felt like because of how I looked I was excluded from being American," he said. "Everybody loves sports. And yet race is a huge factor in American sports, and (it's) under-discussed."

White fans who revere Black basketball stars but have no Black friends might be moved by "Unarmed" to consider the impact of segregation in America, Rivero said.

In mid-October, Rivero set out from Brooklyn by car with his jersey stickers rolled into tubes. The trip has taken him to Louisville, Ky., where Breonna Taylor was killed by police in March; Kenosha, Wis., where Jacob Blake was left paralyzed after being shot by police in August; Milwaukee, Wis.; and Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed.

Rivero found local partners, such as the art directors at Leon, at each stop. He displayed his jerseys at an African-American history museum in Louisville, at a restaurant in Milwaukee and on the streets in Kenosha and in the area known as George Floyd Square around the corner where Floyd was killed. Rivero said George Floyd Square "feels like a spiritual place."

Rivero plans street installations of his jerseys in the Denver area. At Leon, viewers can see the jerseys from the street, as they will be able to at the Galleries of Contemporary Art at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs where "Unarmed" also will be shown.

"The street is for the people," Rivero said. "It's cathartic for public art to address this kind of trauma we're experiencing around police violence."

After Colorado Rivero heads to Los Angeles, where he will work with collaborators to decide on the next phase of "Unarmed." He's been shooting footage throughout his cross-country trip. "Unarmed" might make a movie, after all.