What happens to a city when a global, existential crisis arrives? Do residents fall in line, follow directions and work together? Or can things slide into chaos? For many, it's no longer a rhetorical question.

Plenty of difficult moments arrived along with the COVID-19 pandemic. Unemployment skyrocketed. Mental health declined. Over 700 people in Denver died with the virus, one small slice of the half-million people who lost their lives across the country. When it began, officials at all levels of government attempted to respond in real time. The safest way forward wasn't always clear.

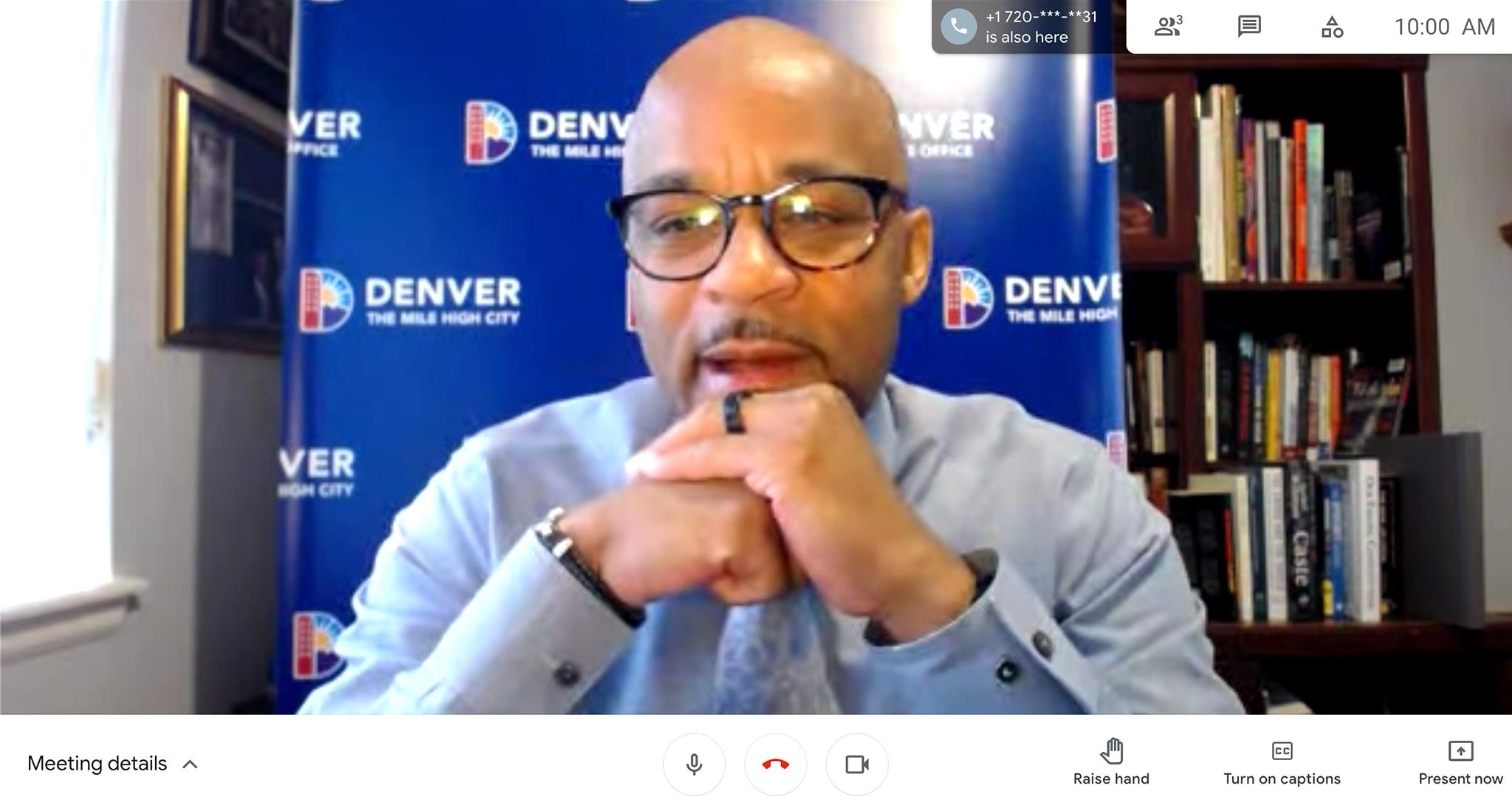

"We had not at all, in the history of our city, been through anything like that," Mayor Michael Hancock said. "And we knew that, at some point, there would be some missteps. We didn't know it would come so early and on something that would, ultimately, become pretty hilarious down the road."

The "misstep" Hancock mentioned was a moment during a press conference on March 23, 2020, around 2 p.m., when he announced the city must shut down. Hancock called attorney Marley Bordovsky to the podium, who clarified that pot shops and liquor stores were not deemed "essential" and would not be allowed to operate.

Across Denver, people dropped what they were doing and rushed to buy weed and booze. The city reversed course just a few hours later, allowing dispensaries and liquor stores to remain open, but the veil had already been lifted. That day became known as the Denver "prohibition" of 2020, a short-lived phenomenon that revealed something raw about our nature in a time of disaster.

"Mixed signals" led to an uproar.

Ron Vaughn, co-owner of Argonaut Wine and Liquor on Colfax Avenue, watched the announcement live on TV.

"Right when they said that, I would guess within ten minutes we got line around the store. And within 15 minutes, there was a news helicopter overhead," he said. "It turned out to be probably more of a health hazard than they thought it was going to be. It was a Monday, so we weren't prepared to handle a crowd like that."

Vaughn said he got right on the phone with his lobbyist, distributors and the Colorado Licensed Beverage Association. Beyond the issue of people crowding into stores, he faced the possibilities that his business would tank and that he'd have to lay off scores of workers. They tried to "put pressure" on the city and state to get the decision reversed.

Meanwhile, his sales were skyrocketing. Customers were leaving with supplies to last them weeks.

"Somebody that would drink Tito's bought a case of Tito's instead of one, and then found out, three hours later, that they really didn't need to do it. It was that governmental mixed signal," he said.

Ben Gellman, who waited in line at Washington Liquor off 20th Avenue, said he immediately felt like he was in a dangerous situation.

"I remember I got a box of wine, a handle of bourbon and was very uncomfortable about standing that close to people," he said.

Hancock's "misstep" was not the only example of mixed signals in the pandemic's early days. At the national level, health experts had not yet begun to stress the importance of wearing masks. Dr. Anthony Fauci would later tell NPR that lack of clarity set back the nation's response in a way that was difficult to correct.

As Gellman waited to get his "affairs in order" at the liquor store, virtually nobody around him covered their faces.

Conor McCormick-Cavanagh, a reporter for Westword who asked Hancock the question that set off the frenzy, said the prohibition was emblematic of so much of the pandemic response. Of course officials were flying by the seats of their pants, he said.

"We'd be giving them too much credit to say that they weren't, and we all were."

McCormick-Cavanagh agreed to speak to us before his editor asked him to write his own piece about the moment. When we asked him why he thinks the three-hour buying frenzy became a cultural phenomenon, why people started selling t-shirts commemorating it, he reckoned it had to do with both the absurdity and the relevance of the prohibition.

"The stakes were really low in this instance, which makes it comical," he said. "I was totally bowled over by that, and I guess that it was a sign of things to come."

Sure enough, consternation rang out across the city as new rules were formulated and changed over the ensuing year. Bar and club owners would lament unclear guidelines as they struggled to raise revenues. Others would complain about "moving goalposts" as Gov. Polis made ever more changes to Colorado's COVID "dial" and vaccine plans.

"It was just, you can't plan for every potential contingency," Hancock said, speaking specifically about the prohibition. "I mean, we're facing a disaster, a challenge that we've not seen before. You don't get this every day. So yeah, things speed up. People are moving. Decisions have to be made very rapidly. And quite frankly, the consequences of decisions we make are huge. So yeah, things are moving quickly and they're coming very fast and furious."

Beyond official announcements, people were swept up in irrational hysteria.

Akio Clark was in Cole, by the Royal Drug liquor store, when he started to see lines forming.

"I saw people rolling stuff out with dollies. The same thing with dispensaries," he said. "People were definitely in a panic."

Bill W., who declined to give his last name, waited in line at Argonaut that day, though he didn't mean to.

"I didn't know there was going to be a long line here, or I wouldn't have come," he told us. "But I stayed in line because, when I got here, I'm like: Well everybody must be in line for some reason."

In hindsight, Bill said he wasn't that worried about buying a case of Coors, his preferred quaff.

"You can always get beer at the grocery store," he said. "Plus, we're in a pandemic! What's more important? Getting beer or staying healthy?"

That's the thing about Denver's prohibition: It's not like liquor was going to become totally unavailable. If the order stuck, people like Bill could still buy their beer in town. Those with cars could have simply driven past city limits to buy tequila and rum.

"I don't think that occurred to people because it was a news event," Vaughn said. "I'm in my seventies. I've never seen anything like it. Not just for my business, but the country and the world, as far as a traumatic event happening that affected people and made everybody feel so helpless."

People were battening down the hatches in other ways. There were massive runs on toilet paper, and the Micro Center electronic store in south Denver also had a line out the door that day.

Clark, who runs a roadside assistance business, said he's been responding to more difficult calls these days. Last week, a woman needed a tow because someone slashed all four of her tires. He said he's seen more people living out of their cars, too.

"People are just doing some real crazy stuff. I've seen people knocking people's windows out for 50 cents in their ash tray," he said. "People feel like everybody's living in their last days."

Shortly after the prohibition, community advocates in some corners of town began warning that violence would tick up as lockdowns dragged on. City crime data later showed their predictions came to pass. In the last year, car thefts jumped almost 150 percent.

Meanwhile, mental health problems worsened in Denver and across the nation. Denver's coroner, Dr. Jim Caruso, said his staff had never been so busy with overdoses and suicide deaths.

Hancock said one of the most immediate reasons to reverse the liquor store closure was to keep hard alcoholics from dying of withdrawal. He heard very quickly from health experts imploring him not to cut off their supply, and it was one of the major lessons he learned from the episode.

Gellman, who waited in line without a mask, said he felt vibrations of catastrophe early on in the pandemic.

"I remember going to the Safeway nearby, and there was just an air in there that really reminded me of going to the grocery store before a hurricane was about to come through, growing up in North Carolina," he said. "It was just really unsettling and scary."

While the stakes in this prohibition were low, and the outcome was kind of humorous, it was underpinned by grim realities everyone had to face together.

"You know, you're talking about something so serious as a pandemic, a virus that we can't see or smell. We're fighting the unknown opponent out there. And yet, everyone took the shutdown of liquor stores and dispensaries so seriously." Hancock told us. "It really was a sad situation. If it wasn't so funny, it'd be sad."