Necessity pulled Ian Harwick into a grim profession.

He was working part time for Denver's health department when he ran into Steve Castro, who runs operations for the city's Office of the Medical Examiner. It's where people end up if they die unexpectedly, usually outside of a doctor's care; the coroner's job is to determine cause of death and keep tallies on things like overdoses, suicides, murders and car crashes.

Castro said he needed Harwick's help.

The city coroner's workload is up 35 percent from last year, Harwick said, which means there's a ton of paperwork to do. Families need the city to sign off on death certificates so they can get insurance claims rolling and move toward closure.

The work is not easy, but Harwick needed a full-time gig.

"It was like: Can I get over my lack of desire to be around death and make that work?" he said, sitting in his office after his team's morning review of new cases. He'd just listened to each story, one by one: an alleged suicide, a likely overdose, an unhoused man found in a Capitol Hill alleyway. It was a slower day than most have been this summer.

"I made it through my first week, and my first kid. Those were the two that were were super-daunting for me," he recalled. "The first week was just kind of gross. Getting used to seeing that every morning."

Harwick said he now sees how his job, and the office as a whole, plays a crucial role in the city. Sometimes, he and his colleagues just talk with grieving people left behind who find reassurance that their loved ones are somewhere safe.

The data they collect is meant to help Denver deal with bigger problems. The numbers can show the city where it's failing. If used correctly, that information may light the path toward a more caring community, Harwick said. At the very least, it's changed the way he views the place he calls home.

"It starts to paint this picture of, a lot of times, what's not working in our city and our state in our society," he said. "But then, now I'm up close and personal with it not working. And that's sad."

"I ended up here because of COVID," he said.

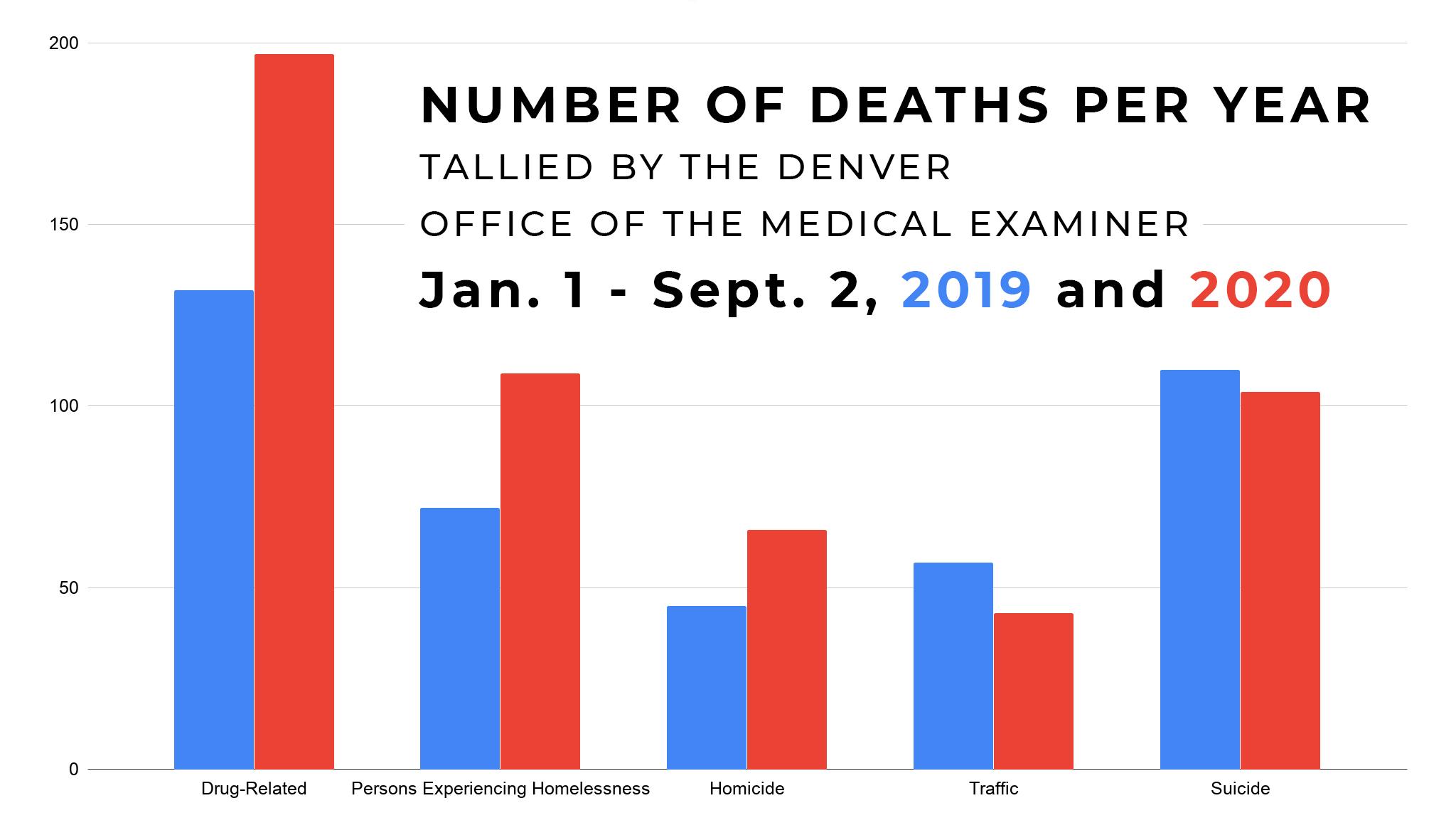

Drug-related deaths and homicides are both up about 50 percent compared to this time last year. Fatalities related to fentanyl have doubled. As of September 2, the office saw 109 unhoused people, which was the total count for 2019.

They expect to perform about 800 autopsies this year, which does not include several hundred more external and chart reviews that do not require an invasive investigation. So far, the office has investigated 1,062 cases in 2020, compared to just 770 in the same time period last year.

While it will take time for researchers to confirm that these trends are related to the pandemic, people on the ground in Denver have warned that changes in behavior due to lock downs and hopelessness stemming from the resulting economic crisis would result in tragedy. Community activists in Montbello and Park Hill have scrambled to create safe spaces for kids who might fall victim to violence or find their way into drugs during this uncertain time. Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen said violent crime may also be related to a purging of Denver's jails, a measure to guard against the coronavirus' spread.

Dr. Jim Caruso is Denver's top forensic pathologist. He's also a hockey fanatic, a former Navy doctor and Harwick's boss. He views the world through an analytical lens. He's not big on conjecture, but he does think the pandemic has contributed to his busy summer.

"Some of it is probably COVID related, but some of it isn't," he said. For one thing, the city's population is growing. More people just means more death. Still, there's likely more to the story.

"There's certainly something to the homicide rate being up, the drug deaths being up. People are not doing what they're usually doing. There are a lot of functional people addicted to drugs that hold down jobs, that do a lot of things in society," he said. "If they normally do drugs in their spare time, now they have a lot more spare time. And unfortunately they may be doing more drugs. And so that probably does kind of relate to the pandemic."

He said about half of the people who end up on his tables have a history of some kind of substance abuse. It's not the best way to draw conclusions about the city as a whole, since autopsies aren't required for many more people who die in the care of doctors. But he and his team are forced to see how common it is for residents to succumb to poor choices and dangerous situations. Caruso said he's seen people as young as 25 dead from alcoholic liver disease. Pedestrians killed by drivers make his colleagues think twice about crossing busy streets.

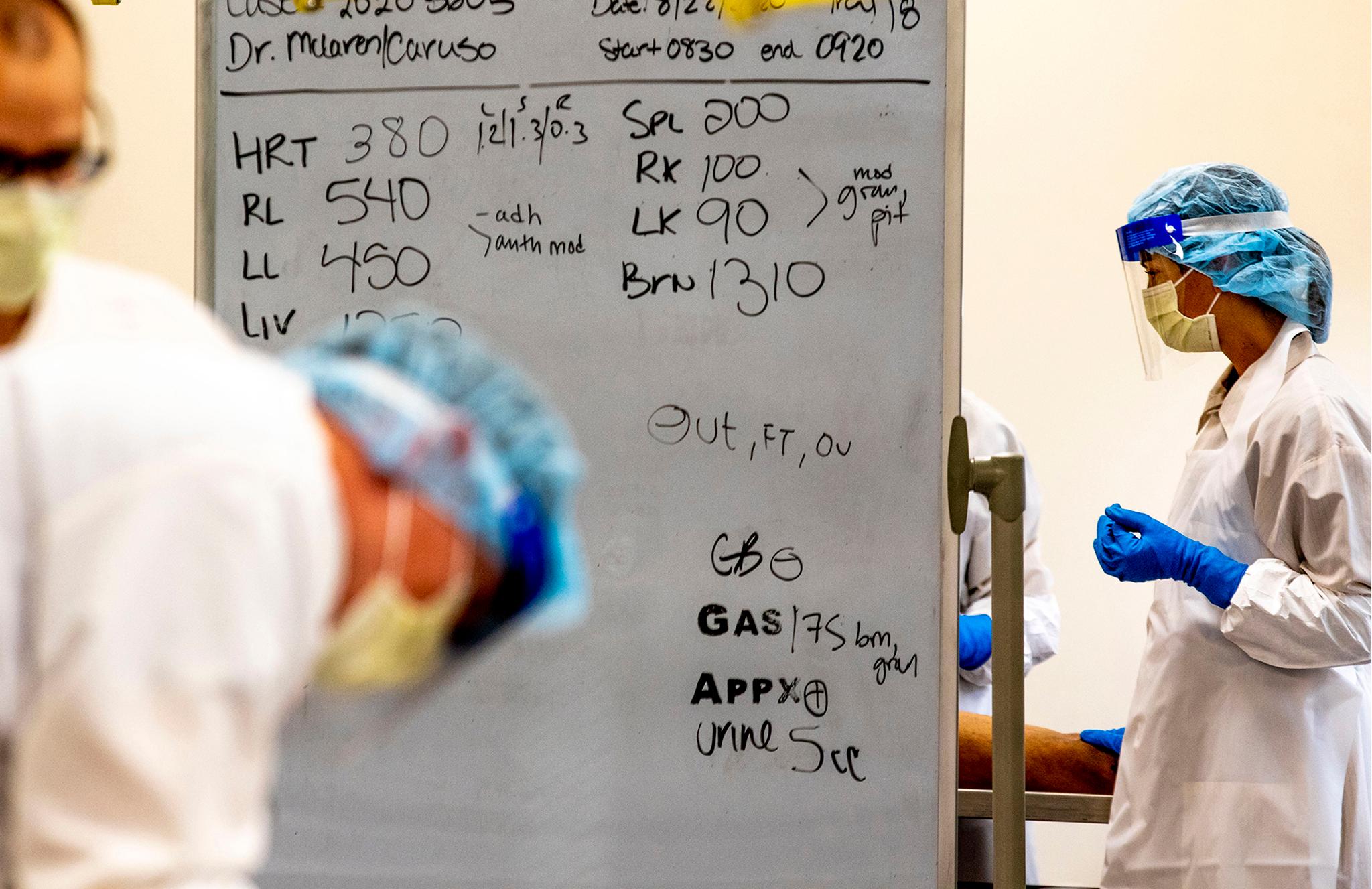

Dr. Sterling McLaren is Caruso's pathology fellow this summer. Now that she's done with med school and a residency, she is learning to run autopsies like her mentor. She also said the pandemic is reflected in her work.

"People are without resources right now, staying at home. Kids that would normally be getting treatment at school or doing physical therapy at school, or occupational therapy at school, those kinds of programs, they're not getting them," she said. "I see people suffering, and I wish we could do something better to help them."

The pandemic has also impacted resources Caruso and his team need.

Though it was a slower day than normal, Caruso's operating tables were still full after the morning meeting. He was working with a tech on someone who'd hung himself, allegedly. His next task was to inspect the body, one organ and muscle at a time, to ensure that's what happened. Foul play wasn't likely, but his job is to make sure.

"The cases all in here today are pretty straightforward," he said as a tech began prepping the man for investigation.

Autopsies take time, especially when they involve bullets or car crashes. Though McLaren and a couple visiting doctors are on hand to help Caruso, he could use some more hands. His office has dealt with staffing cuts as the city's budget suffers during the pandemic recession. Four Denver Department of Public Health and Environment employees took early retirement this week to ease operating costs. Three worked in Caruso's lab, retiring as the workload grew.

"We're being told to cut our budgets, to take furloughs, to do things like that. This is not a good time to be thinking about cutting," he said. "I need more investigators. I need more doctors. I need more admin staff to make sure that the reports go out on time and the death certificates go out on time."

It doesn't help that people who work in his profession are in high demand. There are about 500 forensic pathologists currently working in the U.S., which Caruso said are half as many as needed. He and his staff get attractive offers to relocate to offices in other states nearly every month. He's stuck around because he likes the city; Denver has plenty of sports teams to watch live (during normal times), and he's looking forward to a day when he can use his Avalanche season tickets again.

His staffing concerns go beyond keeping pace with rising overdoses and murders. He needs people like Harwick to keep the paperwork filed so grieving families can move on.

"Families need to make funeral arrangements, need to settle insurance and bank accounts and things like that. Often they need a final death certificate in order to do those sort of things," he said.

As the city suffers, Caruso and his colleagues hope their work might make a difference.

Galena Brown has worked in the coroner's office for 11 years, longer than Caruso has held its top position. She's stuck around, she said, because she feels an almost spiritual purpose in the work.

She and her colleagues deal in taboos. Addiction, homelessness, suicide and death itself are generally avoided in polite conversation. But, here, she's learned to face these things squarely. It's allowed her to focus on what may come next.

"I still have to believe that some of these deaths can be prevented," she said. "You can't help it after being here so long."

Being so close to death can change the way a person views the world. Harwick, who only just arrived, said the job changed him almost immediately.

"It definitely has changed my perception of everything," he said. "There's a lot of cracks and gaps in services and in care. I'm just really seeing it, specifically in the lack of mental health care that people are getting. And also just the sheer number of homeless people that we're seeing come through our office."

Caruso sees this work in the big picture. Statistics and trends can help lawmakers make better choices.

"What's important to me is that this office share those with the people who could make policy decisions," he said. "If you're going to have, for instance, a needle exchange program or a methadone clinic. Well, where should you locate it? Hopefully the statistics that we provide will help the people who are going to make that decision."

McLaren, his fellow, sees herself impacting each person who becomes her responsibility.

"I do see us as their last advocate, and maybe their only advocate," she said, "especially things that might go to court. We will testify on the behalf of our patients."

The job has changed the way she looks at life, too.

"It's given me a perspective to be grateful for the life that I have. To hug my loved ones close and not go to bed angry," she said. "Have a little sense of humor about things and try to live the best life I can but not sweat it too much."

And Brown, ruminating as she stared at a photo of Elijah McClain pinned to her office wall, hopes other people might discover how to value life in that way, too. Lawmakers can't stop someone from driving drunk, and they can't force someone to look out for their friends. Each of us is responsible to one another.

"We've lost a lot of that interpersonal connection. Have you checked in on a friend who was quarantining and also likes to self-isolate? And how is that going for you?" she asked. "What I discovered, too, is the secondary trauma and grief that you carry for humanity. You see people grieve for the planet. Those things are real."

For emergency mental health support, call 1-844-493-TALK (8255) or visit Colorado Crisis Services' website.