One person's nightclub is another person's home for listeners.

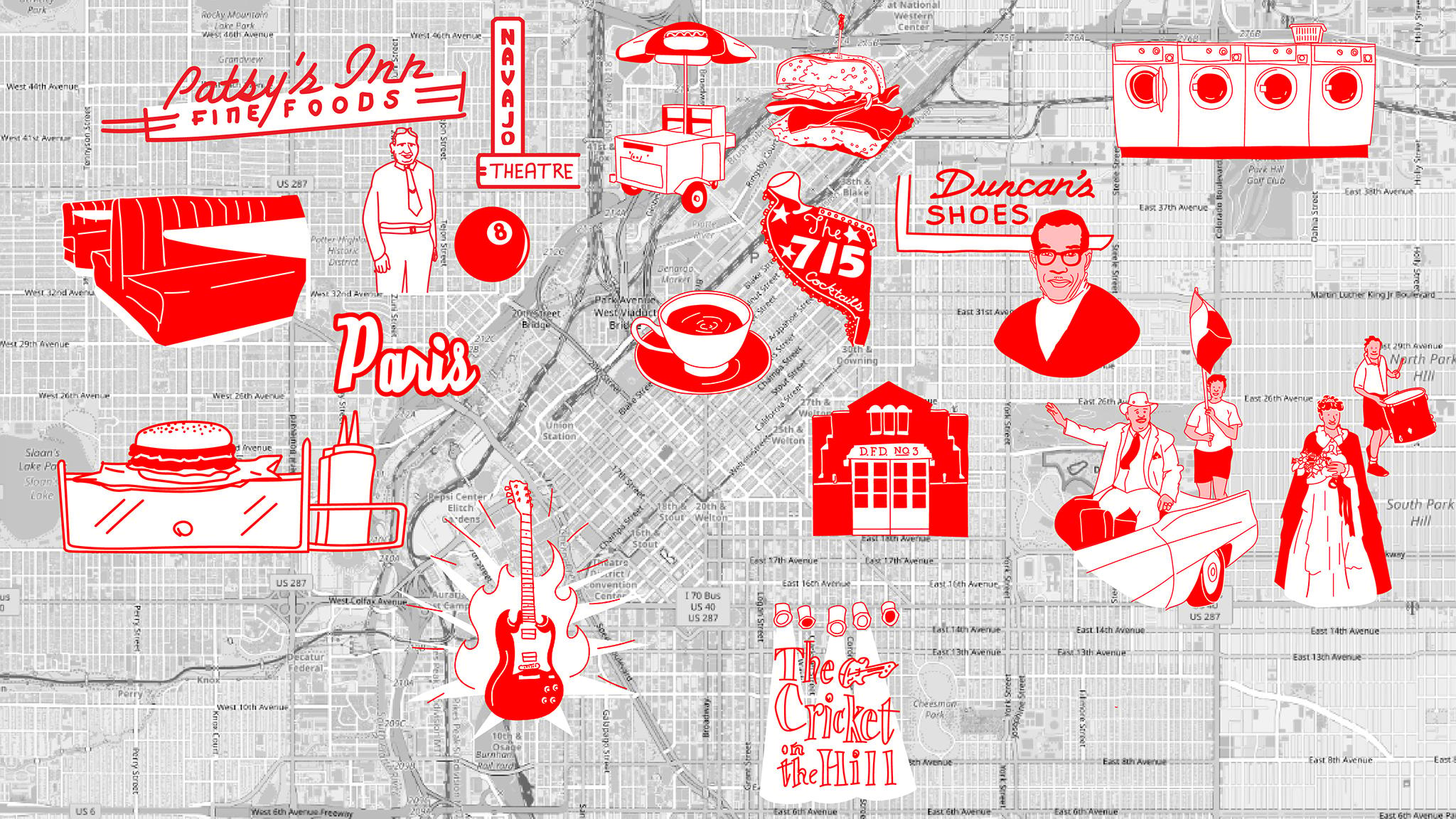

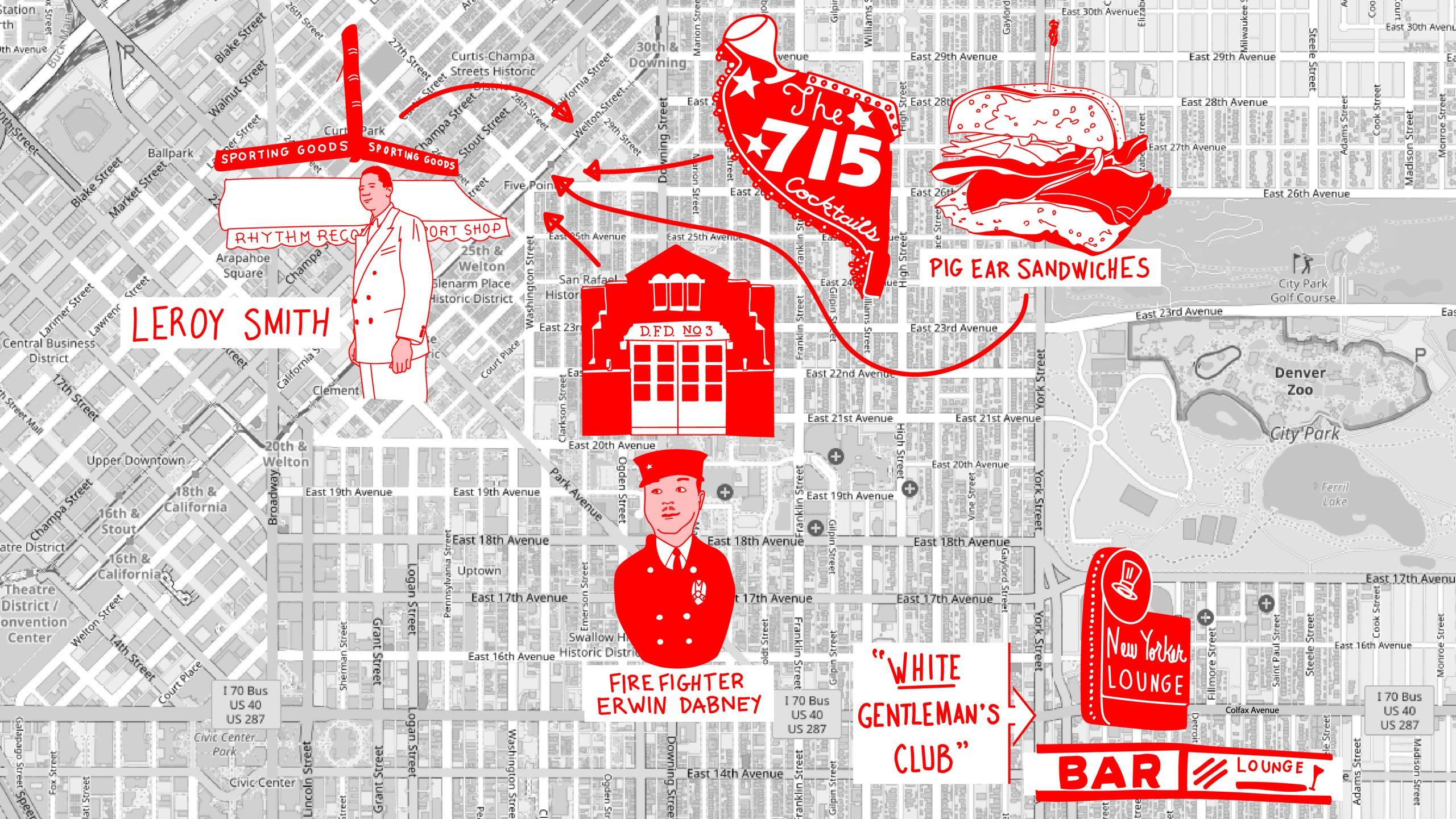

That's what Five Points locals used to call the pig-ear sandwiches at Tamale King in the 1950s, according to brothers Ralph and Charles Dabney, who remember frequenting the food stand once attached to the 715 Club -- the original one, not today's version.

"I've traveled all over the States and the world, and you can never find another pig ear sandwich," says Ralph, 80. "You go up to the window and you tell 'em, I want a listener and a dog, 85 cents, and they never changed the water on the hot dogs. Never."

Charles warns Ralph about revealing the chef's secrets before the brothers quickly jump right back into reminiscing about their younger days, many of which were spent in Five Points along Welton Street because their dad was a fireman at the No. 3 station.

"Every time we screw up, our mom sent us down to the firehouse, to our dad's. After he chewed us out, then we'd go down on the Five Points," Charles said. "That's how we knew everybody in the Points."

They also knew the places. One of my favorite bars and dance floors -- I call it the Seven-One-Five Club -- revived this decade in a gentrifying neighborhood, is their Seven-Fifteen Club, a place the brothers were too straight-edge to go.

"You didn't go in the 715 Club. For us, it was rough," said Ralph. "You had to be -- a certain crowd goes there."

"Gangsters, man," said Charles, who at 82 is Ralph's older brother.

The Dabneys remember Five Points as the Harlem of the West, the nickname earned after local and national jazz greats helped shape its legendary music scene, and after Black professionals broke through a ceiling built of discrimination. But the brothers also remember the neighborhood as diverse, with Mexican, Asian and Jewish Americans contributing to the feel of the place, which had so many local businesses that you could get everything you needed by foot.

What I know as the KUVO building, at 29th and Welton, is their Macklem Bread Company. In the mornings there would be a line around the corner. Their dad would pick up day-old loaves after work to help feed the family's six kids.

My Denver Kush Club is their Rhythm Records and Sporting Goods, where the boys could get a record and adults could get a rifle.

Outside of the neighborhood, my Three Lions Pub at Colfax and York -- which is someone else's DNVR Bar -- is the New Yorker to Charles. It's where, as a Black man, he was told to "find somewhere else" to have a drink.

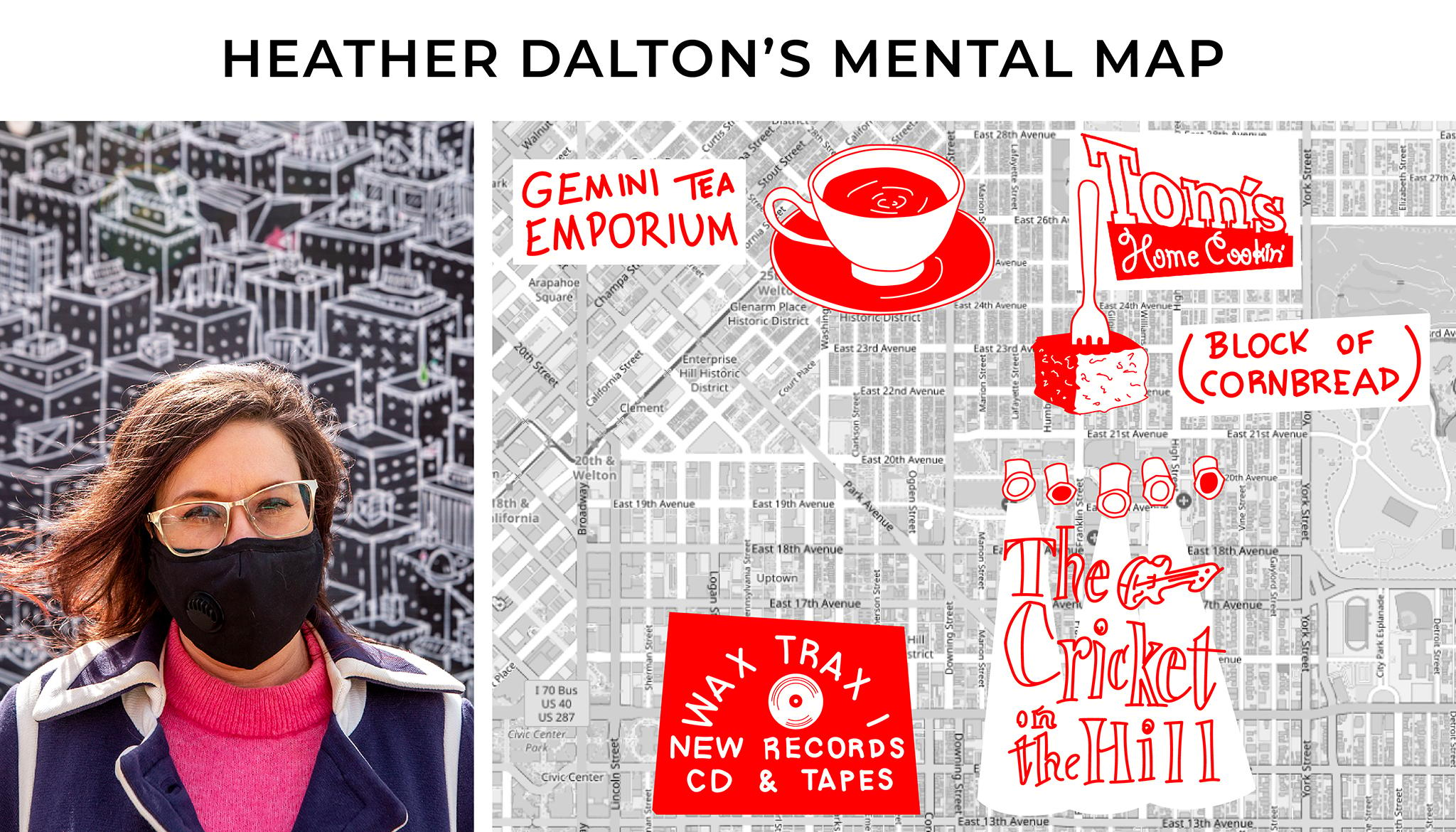

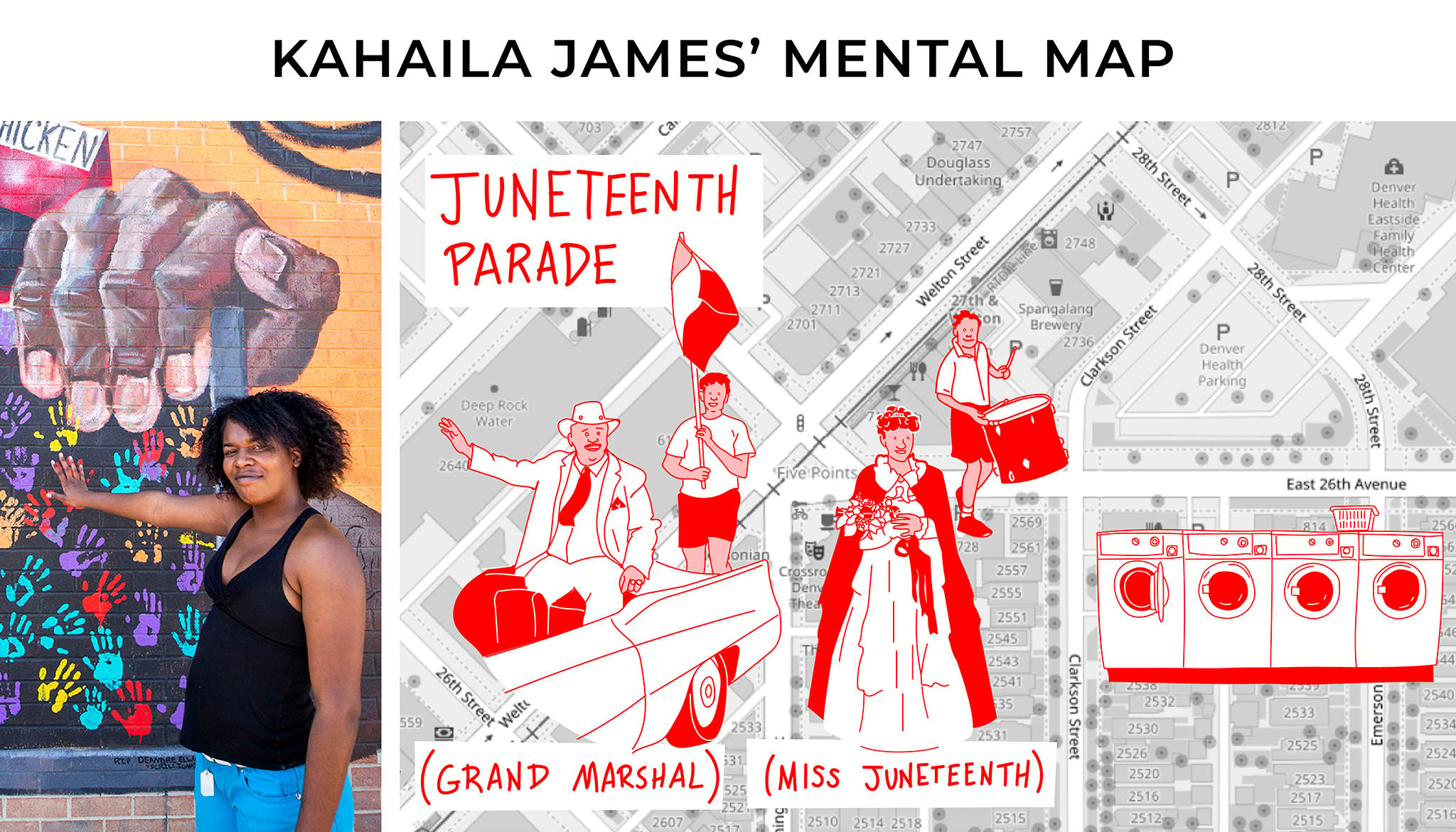

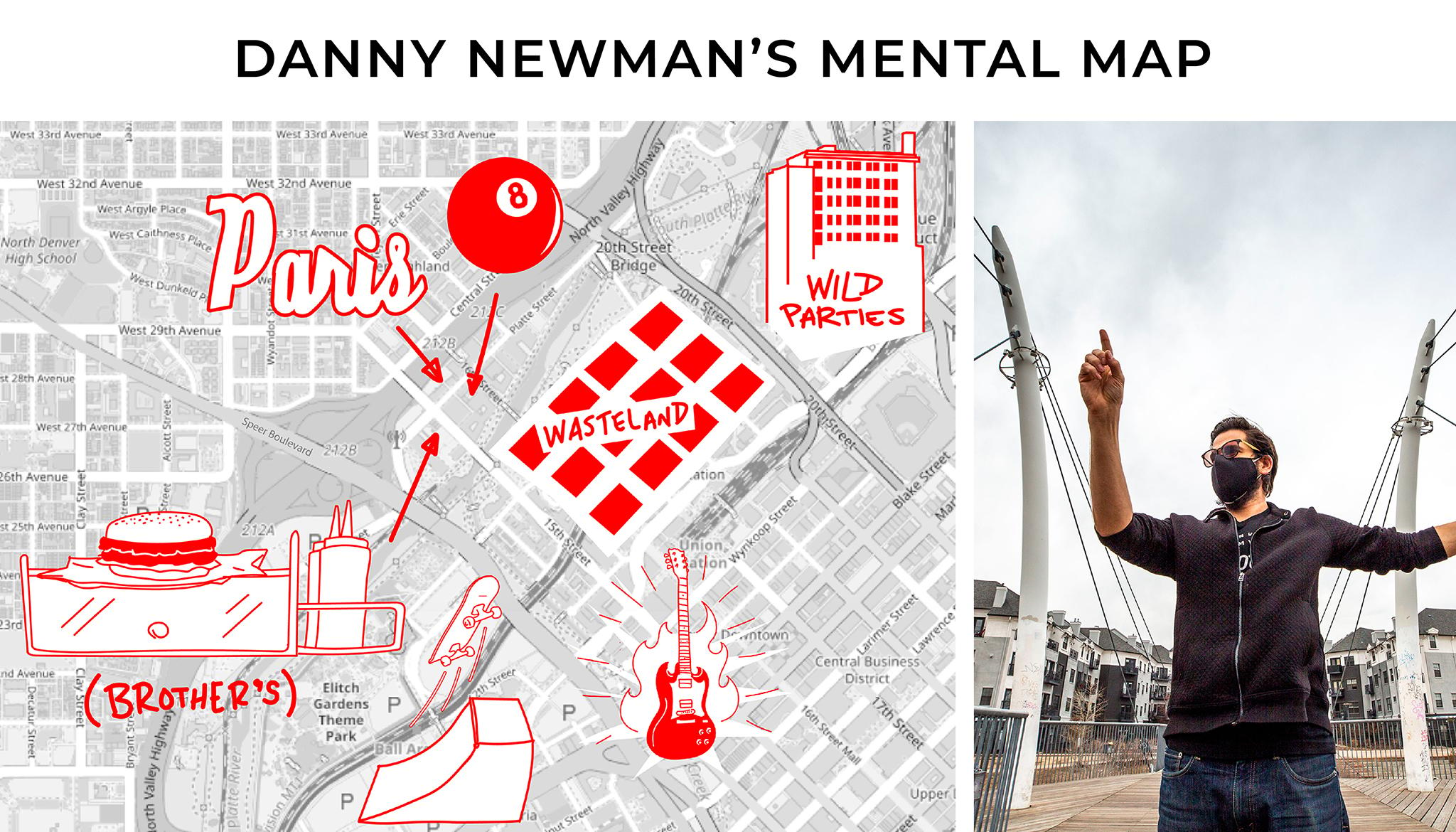

These are some of the places on the Dabneys' mental maps, a personal atlas of memories unique to each one of us. Mental maps shape what a city is to us -- and how we feel about its changes.

"A mental map is just your own personal geography of the city and all of its personal and emotional attachments," says P.E. Moskowitz, an author who wrote about the concept in "How to Kill a City," a book that examined displacement and gentrification in New York, New Orleans, San Francisco and Detroit.

From their apartment in New York, a city that they say has catered to far-flung financial and real estate interests at the expense of locals, Moskowitz says our relationship with our cities is defined by the places and people who make them up. In short, a community.

"So, me growing up in a certain neighborhood, I have a certain outlook on the city and a certain sense of what the city is about and what it can do for me and what I can do for it," Moskowitz says. "And people who didn't grow up here, they have a different one, and people who grew up two blocks away from me have a different one."

As she stands outside Salon Sopris at the corner of 26th and Ogden, where someone happened to throw a brick through a window minutes earlier, Yvette Freeman's mental map is vivid.

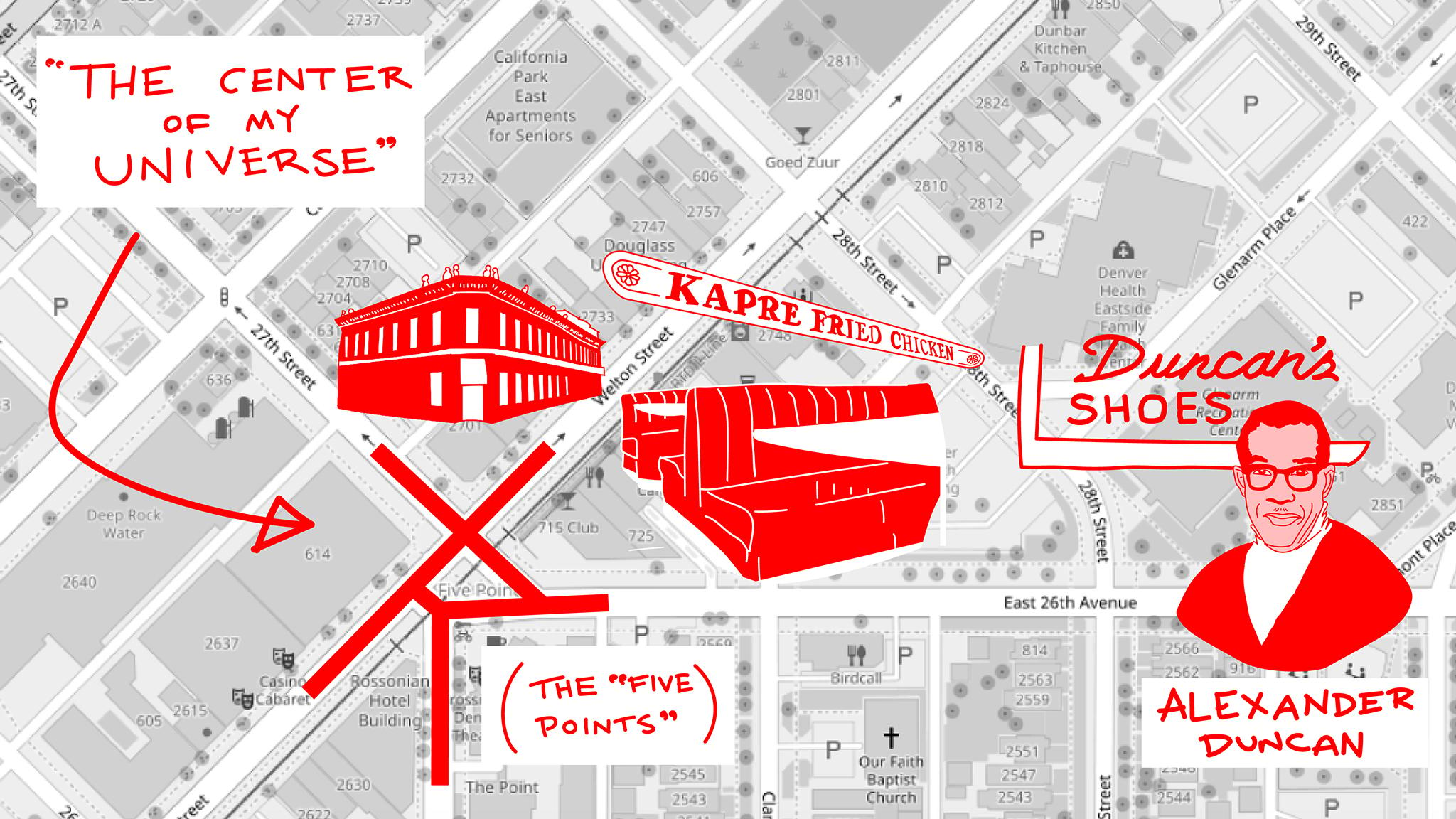

She doesn't see a salon with a hole in the window. She sees Duncan's, her uncle's shoe shop and men's clothing store.

"If you were a Black man in Denver and you dressed, this is where you came," she says.

She remembers the pride she felt every time she passed by the store as a little girl, seeing a sign with her uncle's name on it. She ticks off the things she thinks about when remembering the neighborhood she used to know so well: "family, community, welcoming, joyful, loving, caring."

Freeman grew up in Whittier and Five Points. Her aunt owned a beauty school. Her grandfather was a part-time drummer at the Rossonian. At 61, she's 20 years younger than the Dabneys, who experienced a neighborhood more recently shaped by segregationist policies like redlining. For Freemen, Five Points was a Black haven in a city that was still unofficially segregated.

In the '80s when she set off to work in the mostly white Central Business District to work with mostly white people at the Downtown Denver Partnership, Freeman, a Black woman, put on a face that was only partly hers.

"I had to accommodate the world that I was part of," Freeman says.

After spending her workdays trying to suppress who she was to impress others, Freeman says she didn't breathe easy until she made it back to the Points. She felt safe there, in a neighborhood where most whites probably didn't, in the spaces she knew well with the people she loved.

"I didn't have to do anything but be myself," she says. "I could come here, and I could just let the air out."

That's why on Freeman's mental map, she labels the intersection of Welton Street, 26th Avenue, 27th Street and Washington Street -- the nexus that gives the neighborhood its name -- "my center of the universe."

That was then. In 2014, Freeman moved back to Denver after 10 years in DC to find her Five Points completely gone.

While redevelopment and new builds gave more people the opportunity to live and work in the area, the shock to the local economy from public and private investment after decades of disinvestment had spiked property values and pushed longtime locals out. Some people couldn't afford the taxes. Others sold their homes and businesses, made some money, and moved on. Freeman says others, especially elderly locals, were swindled out of their property by real estate investors.

"Everybody kind of knew everybody, so there was a lot of interconnectedness. And what does it feel like? Nothing," Freeman says. "It feels very disjointed for me."

Freeman knows a lot about change, and not just for personal reasons. In the early '90s when pretty much all of Welton Street's businesses were Black-owned, she co-founded the Business Support Center to try to keep them that way. She and a friend she knew from their days at Manual High School, Brad Segal, had a storefront where a salon called Above Ground now sits.

But it wasn't enough. While Black-owned businesses and organizations still have a place on Welton, the Five Points that was true for Freeman was now false. Her aunt's beauty school above the (now) U.S. Bank had been long gone. But now places like Kapre Lounge, her go-to fried chicken spot, had also vanished, along with myriad other places. The places and the people that gave her a sense of self were largely gone.

"I can't articulate what that loss feels like," she said. "I do not have a community. It's gone. I mean, it really is."

Does that mean that because the people and places of a neighborhood have changed, a community can't exist?

It's a harsh question for Freeman, who has been devastated by change. There's no question that most of the coordinates on her mental map have been erased. Her community is gone, and that's in part because a new group of people have moved in.

"When people come in from the outside, there's no real attachment to place," Freeman says. "It's not a criticism, it's just an observation. And it means something different to them than it does to me."

It's not that new communities can't form from the ashes of old ones, but Moskowitz has a theory, derived from a book called "Gentrification of the Mind," by Sarah Schulman, about why it might be more difficult. As people who grew up in the suburbs flock to cities for the culture, they might bring with them a suburban mindset of space -- your yard, your house, your treadmill.

"And so if you take that mentality and then move it into the city, then you don't get the city becoming your community," Moskowitz says. "You get the suburbanization of the city."

They describe some new apartment buildings, built to cater to the young urban professional set, as "fortresses" with their own gyms, pools, daycares, dog exercise areas, security systems and so on, where anything you want can be delivered. And those things don't necessarily help human interaction.

Still, they're hopeful that new communities of new people can spring up, a take that comes from his professional life having studied displacement in four cities, but also their personal life growing up in New York, where their friends who moved there after college had a completely different orientation to the city.

"Their entire personalities are different because they didn't grow up with this sense of living amongst others," Moskowitz says. "Their focus is more on privacy and kind of getting their own or whatever. And I think that changes. Once you live in a city for a certain amount of time, you learn to kind of, like, see things communally."

Moskowitz hopes there's a new paradigm, aided by protests for racial justice and a pandemic that has torn back the curtain on social inequities and exposed things to mainstream society -- things that people of color and lower-income communities have protested for centuries. In Denver, people are angry and have become more civically engaged since the summer of 2020, filling city hall and demanding changes to their city. It's a different feel than in 2013 and 2014, when Moskowitz was reporting their book and The Hipster eating weird tacos and buying $12 craft beers was a dominant figure in people's minds.

"All these consumptive ways of interacting with the city were the kind of modus operandi -- I think people are, like, tired of that and bored and want something deeper," they say. "They want a deeper engagement."

Freeman doesn't believe gentrifiers are trying to push people out as much as they're doing what makes sense for them in our economic system. The problem for her is what's being built. Developers build homes at a price point that makes them money. In a city that doesn't require affordable housing, that often means price points that are more doable for wealthy and often white folks and less doable for lower-income people and, often, people of color.

She's quick to point out that naming an apartment building after a local Black leader does not make it equitable.

So. What is "original?" Depends on whom you ask.

Before Five Points was a Black community, it was mostly German, Irish and Jewish, though they didn't make the mark that African Americans did on the neighborhood. And while "Denver Native" is a phrase a lot of people throw around, Indigenous people were here first. It's easy to get philosophical about what "original" means because it's a subjective term.

In some ways, Reed Weimer is a stereotypical omen of gentrification. He's an artist -- the kind that moves into a neighborhood that seems a bit run-down because he can afford it and "makes it cool" to the masses. And real estate investors.

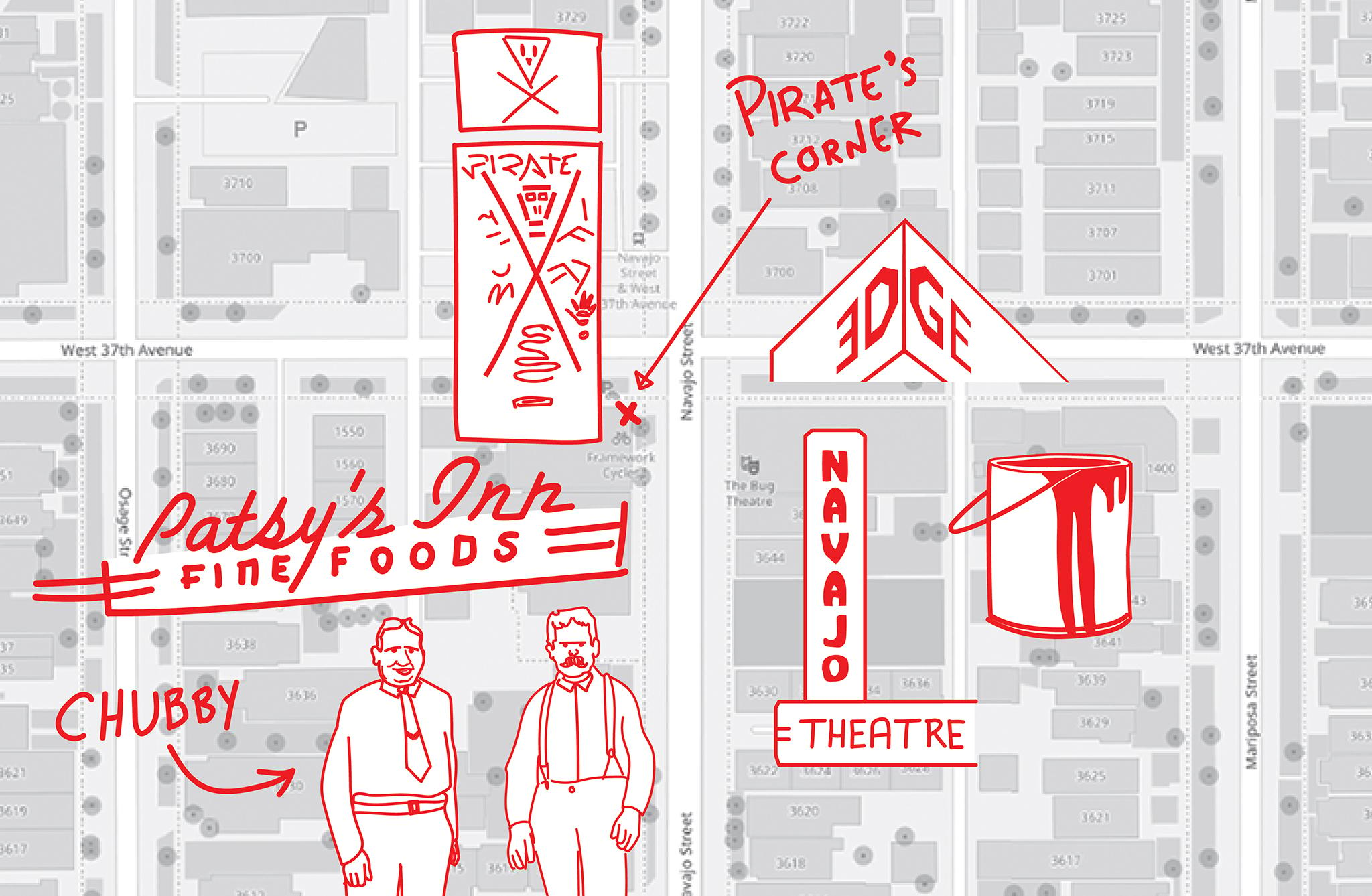

But his story is more complex. In 1982, Weimer and his crew of "punk rock kids" were in search of a place to live and build an artist collective after getting evicted pretty much everywhere they went. They moved into a second-floor apartment at the corner of 37th and Navajo in Highland, the historically Latinx and Italian neighborhood also known as the North Side, now branded LoHi, above what contemporary mental maps would label Pinwheel Coffee.

On the mental maps of his Italian-American neighbors at the time, the ground-floor of the old brick structure he then called home was the general store, where locals bought blue jeans and frying pans. The store was gone, though, and Weimer and his friends started the Pirate art cooperative there, bringing some new creative energy to an area that had been somewhat hollowed out by suburbanization.

"Back in those days, there were just vacant buildings everywhere, and you just moved in," Weimer says. "You didn't really think about why other people had moved out, and I just thought, OK, cities have vacant buildings, and if you don't mind fixing things up, you can get into them."

That's exactly what Weimer and his friends did, eventually buying that corner building. Then they bought the boarded-up building across the street, a one-time nickelodeon movie house that has had various aliases over the years -- The Navajo, The Avalon, and the World Theatre -- and fixed it up. It's now known in contemporary mental maps as The Bug. That's what the neighborhood people called it, Weimer said, because it had bugs.

The purchase started a domino effect, Weimer says, in which between 1985 and 1997, the owners of various buildings on the block knocked on his door and asked him to buy theirs "because people were still leaving the city at that time," he said.

Over the years, Weimer and his crew bought and maintained enough property to create an artist's enclave in the neighborhood with galleries, studios and other creative spaces. While they created a new community, they also lived alongside the existing one -- to an extent. He became friends with George "Chubby" Aiello, part-owner of Patsy's Inn, the famous Italian restaurant that closed in 2016 after 95 years. When Weimer was asked to turn racy pictures around because they bothered the old ladies who passed the Pirate gallery on their way to church at Mt. Carmel, he did.

"When we were here with the galleries, we were kind of interlopers and we wanted to fit into the community," he said.

Weimer's and his friends' goal was always to create stability for a community of artists -- a place they could live and work creatively and affordably. And they did that for about 30 years. But when galleries moved out, Weimer didn't have a plan B. He was still paying mortgages and needed to rent the space to make ends meet, so the storefronts changed. The Bug Theater remains, but a bike shop, a coffee shop, a salon and a pilates studio now sit where artists once created and displayed their work. That cycle of change began long before he arrived.

"They were neighborhood stores before, now they're neighborhood stores again," he says.

It was never Weimer's dream to have a real estate portfolio or be a landlord "because as soon as you become the landlord, everyone hates you," he says. At the same time, he and his artist buds didn't want to keep moving around, and buying the buildings made that happen, at least for a while. Highland as a whole has long been gentrified -- the average home price is over $660,000 -- and Weimer knows he played a small role, if unintentionally.

"We were the harbingers of change without knowing it," Weimer said. "The second you show up in a new place, you've changed that place. 'Cause you're there and you're not the same thing that was there. You know, you have to own that."

As long as he owns them, Weimer's historic buildings will remain even if the insides change. But the built environment, which defines our sense of place and informs our sense of self, is constantly changing.

That's what cities do. Denver has grown by about 260,000 people since 1990, and homebuilders and job creators have tried to meet that demand.

"It's not about people in smoke-filled rooms making secretive decisions about these things, although that does happen," he said. "But it's more about, if real estate is purely about profit, then it goes to the areas of highest return, right?"

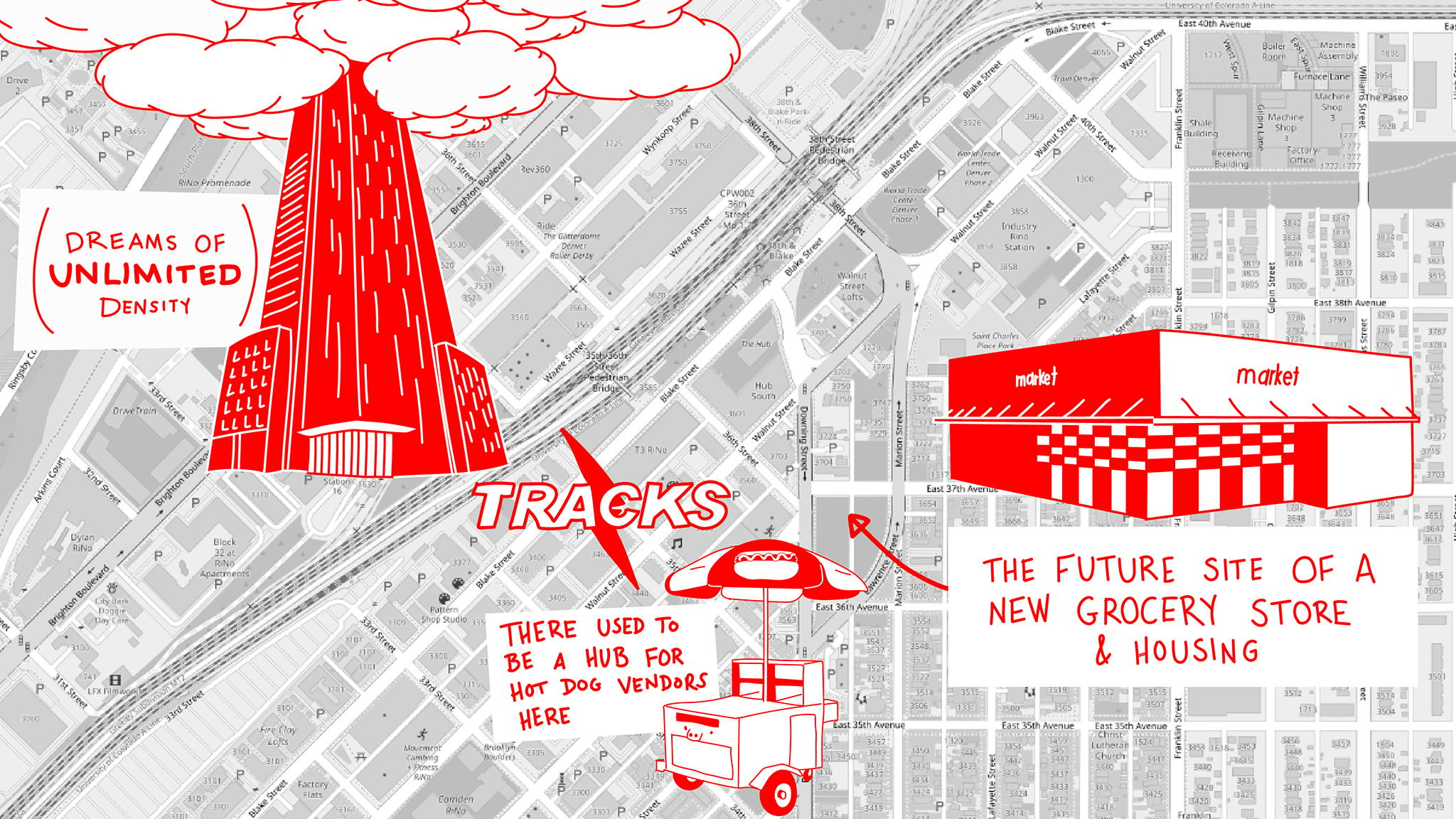

Developer Andrew Feinstein is a well-known home builder whose Exdo Development's projects have helped transform -- and are still transforming -- parts of Five Points and Cole in the heavily branded RiNo Arts District.

Our recent walk along Larimer Street is paused as he takes a call from Mayor Michael Hancock. When he returns, he points to a blocky, three-story building with businesses on the ground floor and homes on top. Before it was demolished, the space housed a commissary for caterers and hot dog vendors who had carts downtown. Exdo relocated them to another property.

"From a business standpoint, that was a good little business for us to relocate to a larger facility, and we actually have more caterers and more food trucks now because we have a larger facility," he said.

Does he have an obligation to relocate the people his developments push out? "Probably not," he says, but it was a smart business decision. Plus he grew up in and around Denver and, though he knows he has played a role in its gentrification, he sees himself as a "capitalist with a heartbeat."

"We created more affordable housing at this train station than any train station in Denver," Feinstein says about his developments anchored by the 38th and Blake RTD station.

Feinstein looks up at a 12-story building with 380 homes.

"I'm thinking 25 to 30 of those are affordable," he says.

"Affordable" is a subjective term with a government definition, but Feinstein says what's there is better than nothing.

"The affordable housing crowd is going to say there's not enough, but still, there's 30 affordable units and before, there were zero," he says.

He says his projects, which are mostly market-rate homes, don't get enough love (including from Denverite) for the income-restricted units sprinkled in.

He knows his developments create different mental maps for people.

They are apartment homes for some, temporary construction jobs for others, and permanent jobs for people inside the ground-floor business space coming, like a new grocery store in Cole. Feinstein also notes that once property values rise because of redevelopment, owners can make a huge profit -- "generational wealth" in some cases, he says.

But Feinstein says he also knows that the booming market for him means people get priced out.

"And if they want to stay in this community, now they can't afford to be here because the apartments are too expensive and they don't want to live in apartments anyway," he says. "That's where the displacement comes."

He says he wants government-mandated requirements for affordable housing set at 10 percent and unlimited height for buildings near train stations to meet the demand for housing and create a vibrant, walkable area. But he's not apologetic for how he's changed the face of the area. He believes his own mental maps of the city helped him make it better, and wants residents to benefit from his work, not loathe it.

"We took this post-apocalyptic relatively obsolete warehouse district and we've created a new downtown," he says. "I'm proud of that."

For Feinstein, the positives outweigh the negatives. He doesn't lose sleep at night, he says, because he truly believes that what he's doing is best for his city in the system we have.

The pattern of gentrification and displacement that has characterized Denver and other American cities is not surprising to Moskowitz. Nothing about our economic system indicates any other outcome, they say.

"I don't really believe most people in the world are thinking they're doing something evil. I just think a lot of people think, this is how it works and you have to adapt to that," Moskowitz says. "That's what they do is they try to adapt to the system. But for people like me, for a lot of other people, I think we're sick of the system and having to adapt to it. We'd rather the system adapt to us."