Denver's Inverted L paints with a broad stroke where inequities persist in our city. It doesn't seem to be going anywhere, at least anytime soon, but we wanted to know what it would take to get rid of the L using magic wands or, you know, policies and funding.

The Inverted L pattern loosely traces I-25 and I-70 and shows up on Denver maps over and over again. It typically tracks with race and income. For instance, a Colorado Health Institute map about childhood obesity rates shows that lower-income neighborhoods and neighborhoods with more people of color are more likely to have kids with an unhealthy body mass index compared to white and wealthier areas. Still, the L is an indicator, not a hard-and-fast rule.

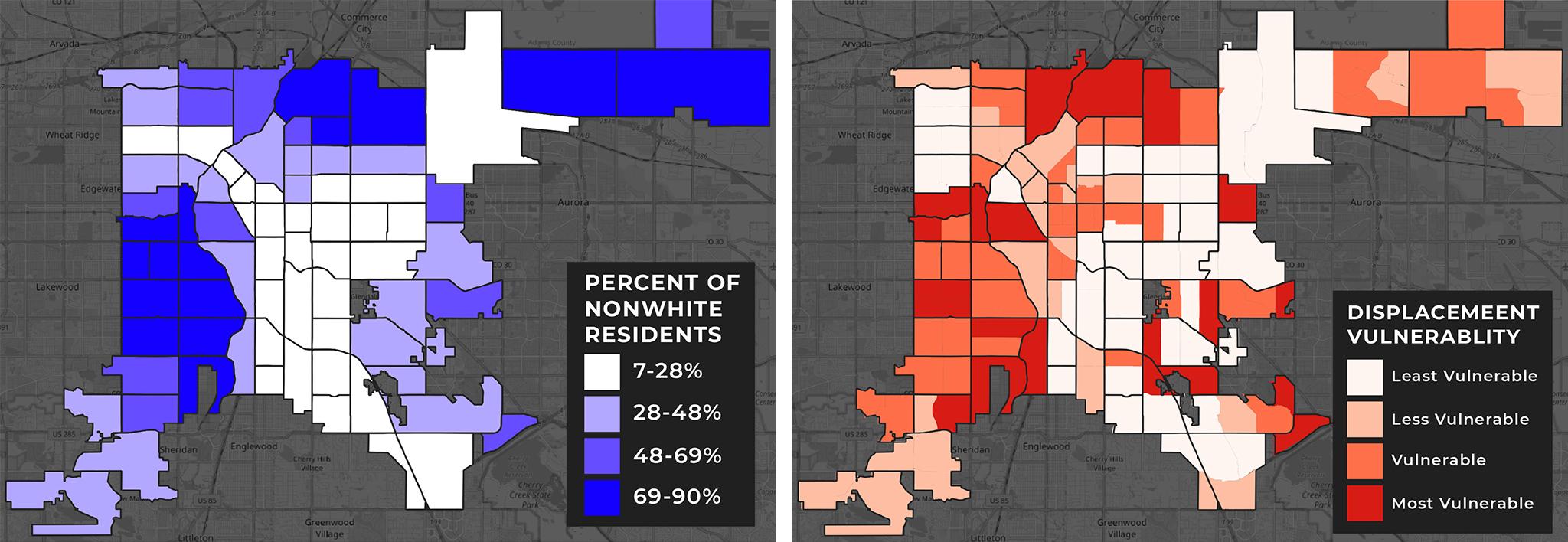

One particularly stark inequity revolves around housing, a key indicator of displacement from gentrification.

Getting priced out of a neighborhood is more likely in lower-income neighborhoods, often where larger concentrations of Latinx and Black residents live, according to data from the city's housing department.

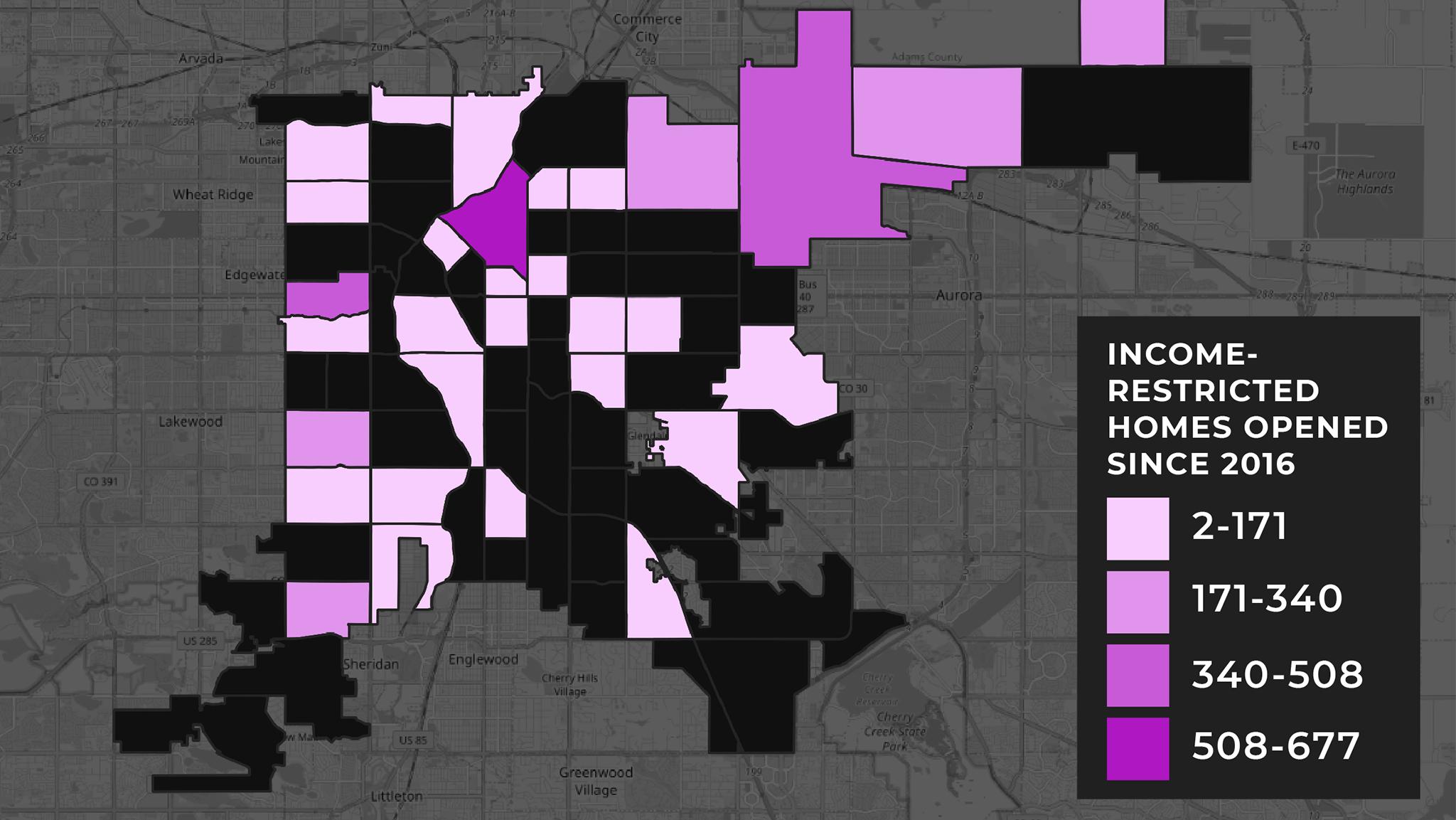

Over the last four years, 69 percent of the "affordable homes" -- dwellings that cost 30 percent of the household's income or less -- preserved or created were in neighborhoods "vulnerable to displacement," data shows.

Britta Fisher, head of Denver's Department of Housing Stability, is wary of simply equating more income-restricted homes with an end to displacement. It's not simple, she said. Inventory is important, but so is ensuring those units cater to the right residents. Do they have enough bedrooms for a family of six? Is the home near good transit?

Then there are the centuries of racism, embodied by things like redlining and pollutive highways being built -- and expanded -- through minority neighborhoods that have drawn lines of haves and have-nots.

"The systems have built up around that structural racism," Fisher said. "And so I think it's incumbent on all of us to think about how we not only think about how to mitigate impacts but actually dismantle structures."

Waving a magic wand isn't a thing Fisher or anyone else can do, but she has some ideas for what might turn things around.

Some ideas are already in motion -- though they came well after displacement ramped up -- like using more city tax dollars than ever before to finance income-restricted apartments, condos and other housing types.

It took until 2019 for Denver to have a true housing department and until 2016 for elected leaders to create Denver's first-ever affordable housing fund, a guaranteed, steady stream to preserve and build affordable housing that was doubled two years later. Between 2016 and 2020, the city helped preserve and create more affordable homes -- 3,768 -- than it did over the previous nine years combined, according to Denver's housing dashboard. Developers contributed another 904 units over the last four years using incentives from the state and federal government.

As you can see, those homes have been spread around the city, inside and outside of the Inverted L:

"It takes a while for those plans to get to the homes through the financing and construction, and now we see the reality of those fruits," Fisher said.

Those efforts are supported by a sales tax to fight homelessness, passed by voters last year to expand tiny home villages and provide shelter, homes, and onsite services to the unhoused. Budding zoning policies incentivize developers to build income-restricted homes.

And still, Denver is far short of providing enough housing for people who need it. As of 2018, Denver needed almost 106,000 income-restricted homes, according to the housing department. As of 2020, Denver had 24,000. It would take until 2053 to make ends meet if builders kept the pace of the past four years, and that's if the right level of affordability gets baked in; data shows that Denver's poorest residents have the fewest housing options available to them.

To scale up, Fisher points to the federal government, neighborhood gatekeepers, and a "prioritization policy."

The Biden administration's plan to expand housing vouchers -- a plan that depends on Congress' support -- gives Fisher hope. Vouchers are federal tax dollars that fill the gap between people's income and their rent by paying landlords the difference. Right now, vouchers are reaching just a quarter of Americans who need them, according to the Urban Institute.

"That would change things very fundamentally," Fisher said of more vouchers.

She also hopes the federal government expands federal tax credits for developers, the traditional incentive for builders to bake affordability into their projects.

Fisher points closer to home, though, too. Denver neighborhood organizations have a history of fighting projects that include affordable homes and policies that would allow more people and places in more neighborhoods.

"I think that it would be a lot easier if neighbors welcome more neighbors," Fisher said about getting rid of the Inverted L. "One of the ways that we don't have people pitching tents in our right-of-way is that we have more housing in our neighborhoods for people to come indoors, and it would be seen as a benefit to have affordable housing and income-restricted units in one's development and in one's neighborhood."

Also, here's a little breaking news: The housing department is hiring someone to create and manage a new "prioritization policy" that Fisher said will help match people with the right income-restricted home.

The policy would take personal things into account, like whether someone has been displaced before or whether they're in danger of being displaced for the first time, in order to give preference to the people who are most in need of the precious little housing that's available.

"That's not something that's done yet in Denver," Fisher said.

OK, on to de-L-ifying trees, which the head forester said is sort of on you and me.

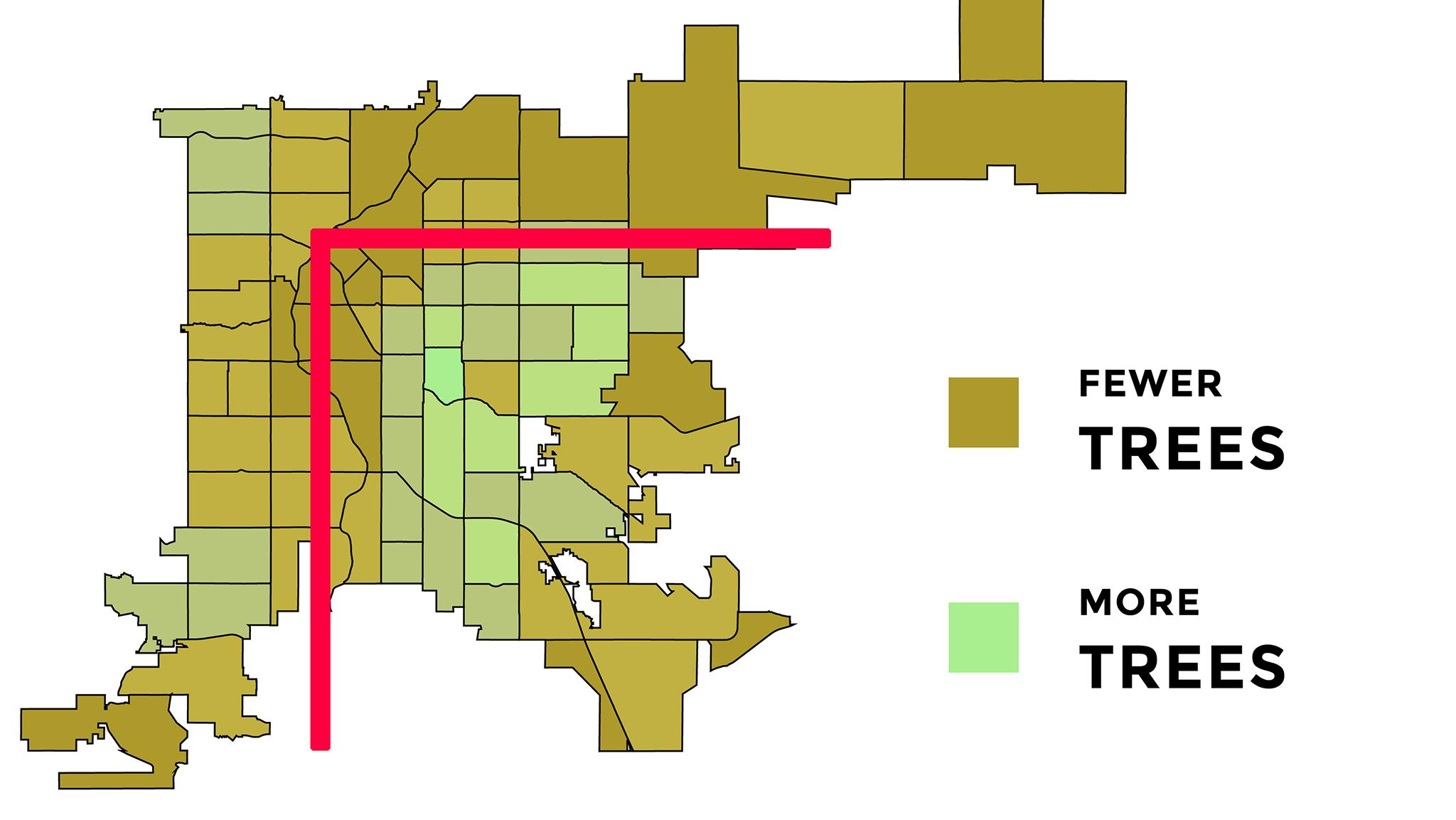

Denver's tree canopy sits at about 10 or 11 percent coverage, city forester Mike Swanson estimated, though other numbers appear in official city documents because the science is a bit squishy. Denver aims to have 18 percent of the city covered by leaves, including in the lower-income areas and neighborhoods with more people of color, which tend to have less leafy coverage than whiter and wealthier areas, though the forester is working on balancing that out.

First things first: The city government only controls between 13 and 15 percent of Denver's canopy, mostly at parks, Swanson said. The rest is on private property.

"We cannot truly manage that ourselves," Swanson said.

So if Swanson could wave a magic wand, he would wave it in a way that gets way more people to plant and maintain trees -- the kinds that thrive in Denver, a city where trees have a tough time because most aren't native and we live in an arid climate in a drought state. It also costs money, time and effort to plant the oxygen-givers and keep them alive.

Because there's no magic wand, Swanson and his team are using the next best thing: money and people power. Since city voters passed a sales tax for parks, the Department of Parks and Recreation has used some of the money to prune trees in parks on the under-invested side of the Inverted L. Pruning sounds lame, and is far different than planting new trees, but it's just as important because it keeps trees alive longer so they can grow taller and contribute to the canopy.

"A lot of these trees have dead wood, they haven't been pruned for 30 years, so if you manage them through pruning you can help them be more resilient in storms like the most recent one," Swanson said. "Just getting the deadwood out helps with insect infestation and we restructure the trees to make the crown of the trees healthier -- more sunlight, more air going through them."

Swanson is focusing on planting new trees with an Inverted L lens, both at city parks and in people's tree lawns where ash trees, endangered by the emerald ash borer, will eventually die. Denver has been planning for the infestation for years, and giving away free replacement trees is part of the program.

"We try to get ahold of a homeowner or a property owner, and we'll remove the tree for free," Swanson said. "We'll grind the stump for free. And then we really want replacement trees, and we're willing to plant those for free."

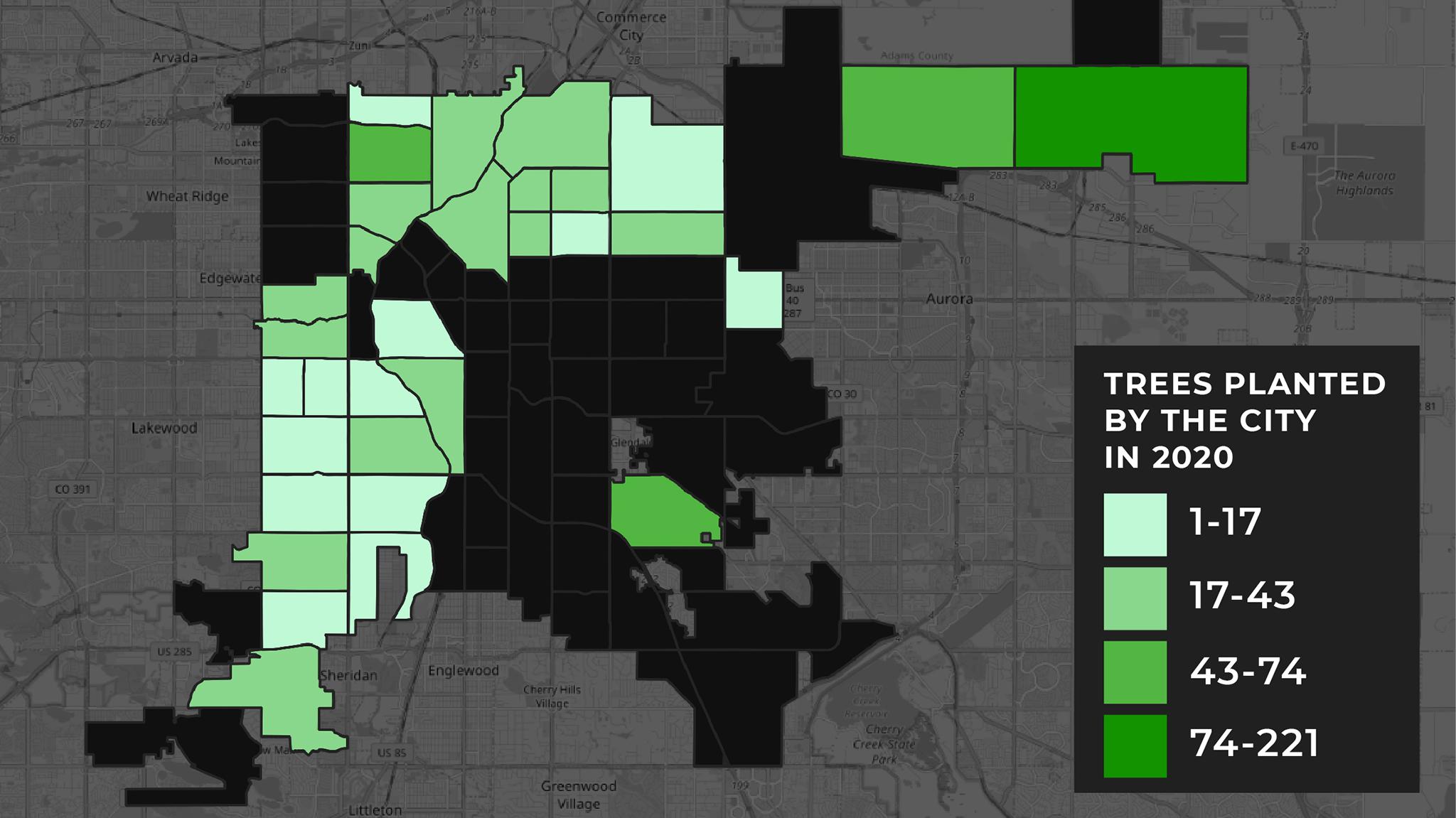

As you can see, recent tree plantings have focused on neighborhoods that typically fall on the under-resourced side of the Inverted L:

The problem is, he only gets about a 40 percent response rate. Not everyone knows or cares about trees, which can make the air cleaner and cooler. So Swanson and his team are trying something new. Starting with Valverde and Barnum, urban foresters are sticking with concentrated areas to ensure the trees are watered and cared for, instead of just planting trees and leaving. They're trying to build relationships with locals because otherwise, Swanson said, some trees won't make it.

"I'm thinking it's a paradigm shift for people," Swanson said, "because they're worried about food on the table and tires for the cars and new roofs for their houses. It's really about the greater common good. So that's why I really wanted to focus not only on the work, but also on the relationship side."

It's going to be tough to undo the Inverted L in terms of the tree canopy, short of massive adoption of trees by city residents -- and the right ones, said Swanson, not the Siberian elms and silver maples that have a short life span here. Swanson said he can lean on nonprofits like the Parks People, which provides free and inexpensive trees to residents once a year, and others like the Nature Conservancy and Trust for Public Lands.

"I can't sleep at night sometimes thinking about it," Swanson said.