Three years ago, the Denver Police Department started auditing the racial makeup of people arrested and cited by officers. The department sent us its data a few weeks ago, and we crunched the numbers to see what we might learn.

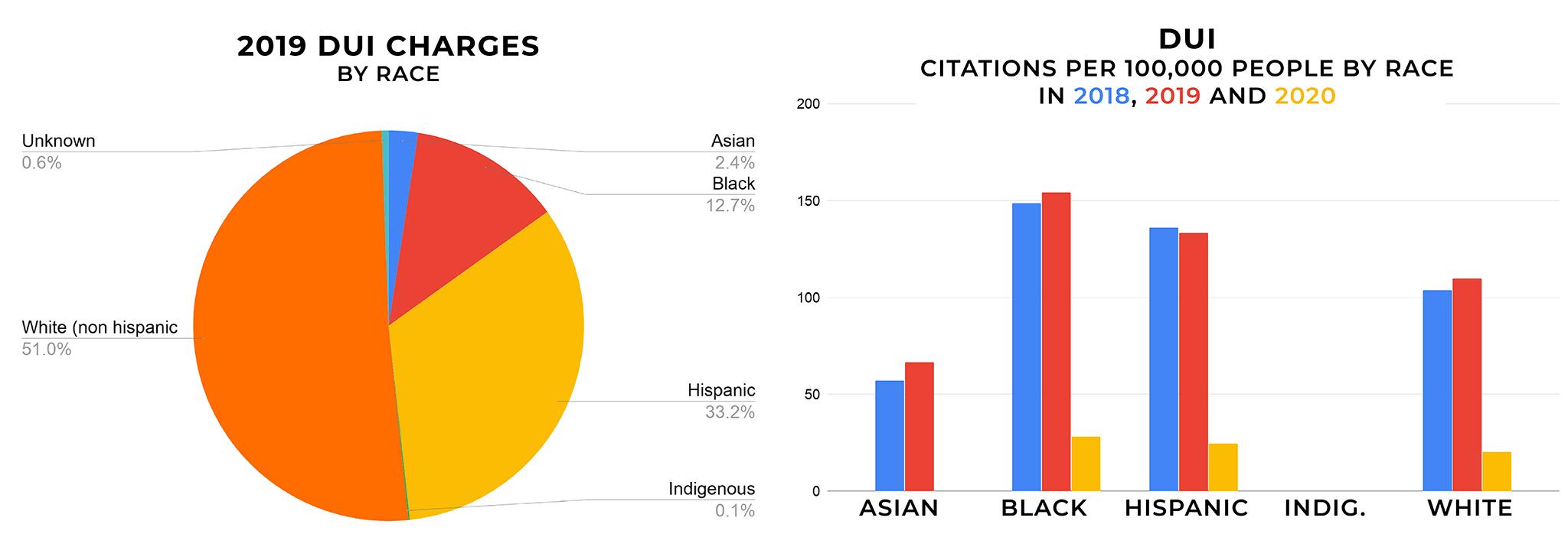

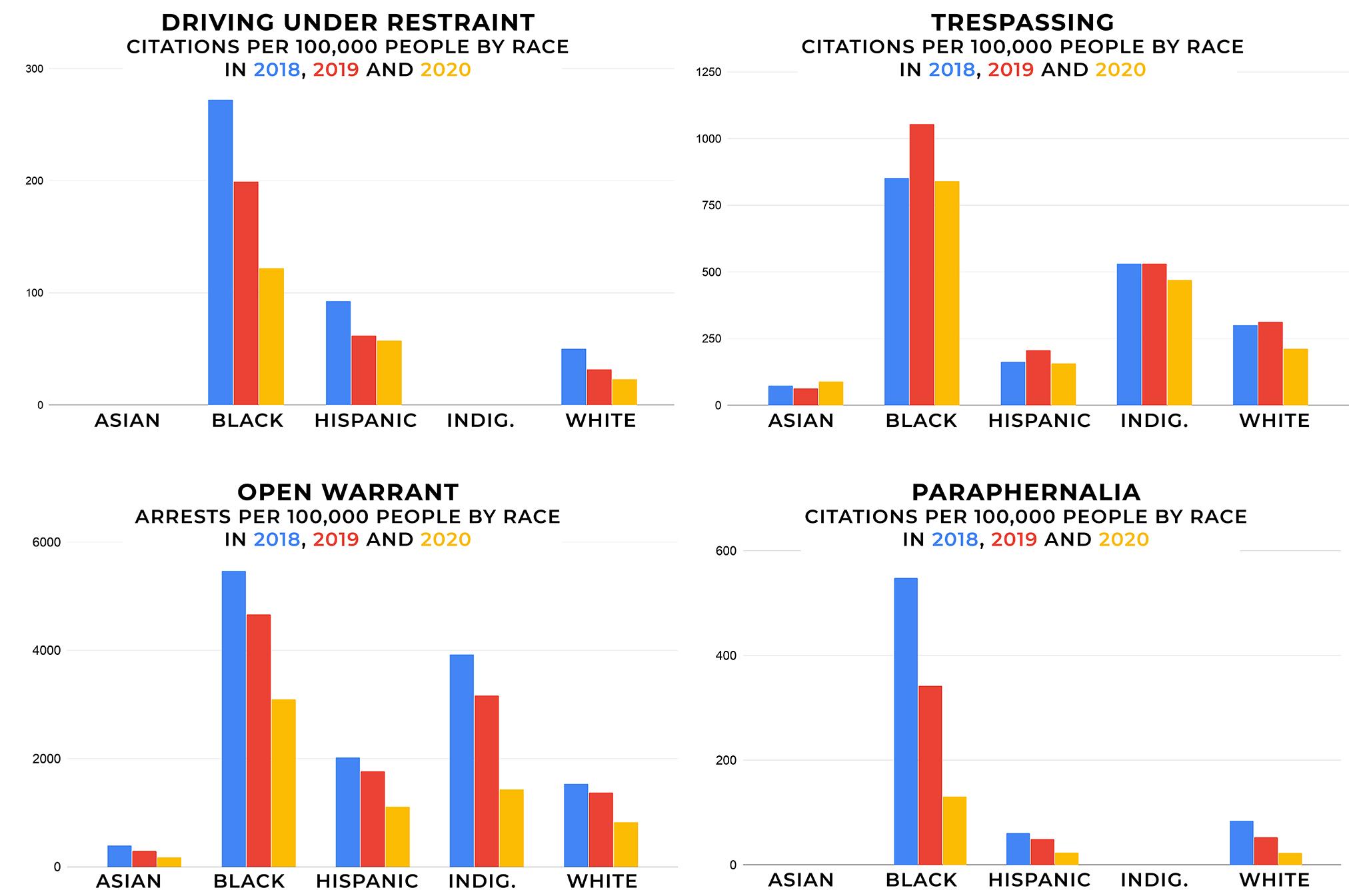

We began with the ten most represented crimes in the dataset. Arrests for outstanding warrants topped the list, followed by possession of a Schedule 1 or 2 drug, assault, trespassing, shoplifting, failing to report an accident or call the police, drinking in public, driving under the influence, driving with a revoked license and possession of drug paraphernalia.

In all ten categories, Black residents represented a greater share of arrests or citations than their slice of the city's population, which is slightly less than 10 percent.

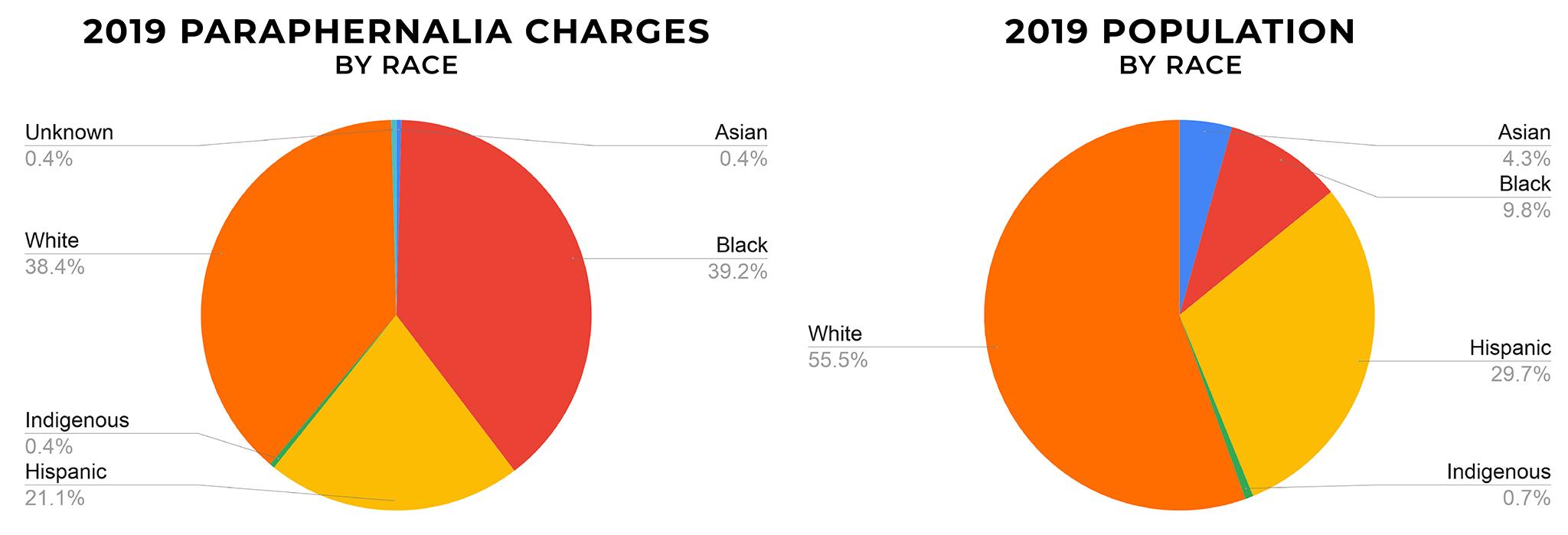

Sometimes the disparity was huge. In the case of paraphernalia tickets, Black residents represented about 4o percent of all charges between 2018 and 2020. They also represented about 30 percent of citations issued for driving with a revoked license and trespassing.

Among the top-ten list of crimes, racial and ethnic data among DUI arrests came the closest to matching Denver's overall population. Black residents accounted for about 12 percent of these arrests between 2018 and 2020. White residents, who make up about 55 percent of the population, accounted for about 50 percent. Hispanic residents accounted for about 33 percent of DUI arrests and represent about 30 percent of Denver's population.

For the charts in this story, we broke down the data DPD gave us to more clearly compare citations between racial groups year over year. (If you're interested in the technicalities, we divided the number of citations for each racial group by that group's population numbers. We ran our math by two experts, MSU Denver associate professor of criminal justice and criminology Hyon Namgung and Cathy Durso, a math and statistics professor at the University of Denver. Both approved our methodology. At Namgung's suggestion we didn't include data for years with very small citation numbers, so that's why you'll see some blank spaces in these bar charts.)

"That is not surprising," Namgung said after he looked at the disparities laid out in the data. "These kinds of results can be found in many other cities in the country."

The results match statewide numbers, which the state is required to collect annually. In the 2019 report, mandated by the 2015 Community Law Enforcement Action Reporting Act (or CLEAR), researchers wrote that Black Coloradans represented 12 percent of the 209,000 arrests and summons recorded that year but only made up 4 percent of the state's population. Hispanic Coloradans represented 29 percent of arrests and 20 percent of the population. White Coloradans comprised 71 percent of the state's population and accounted for 57 percent of arrests.

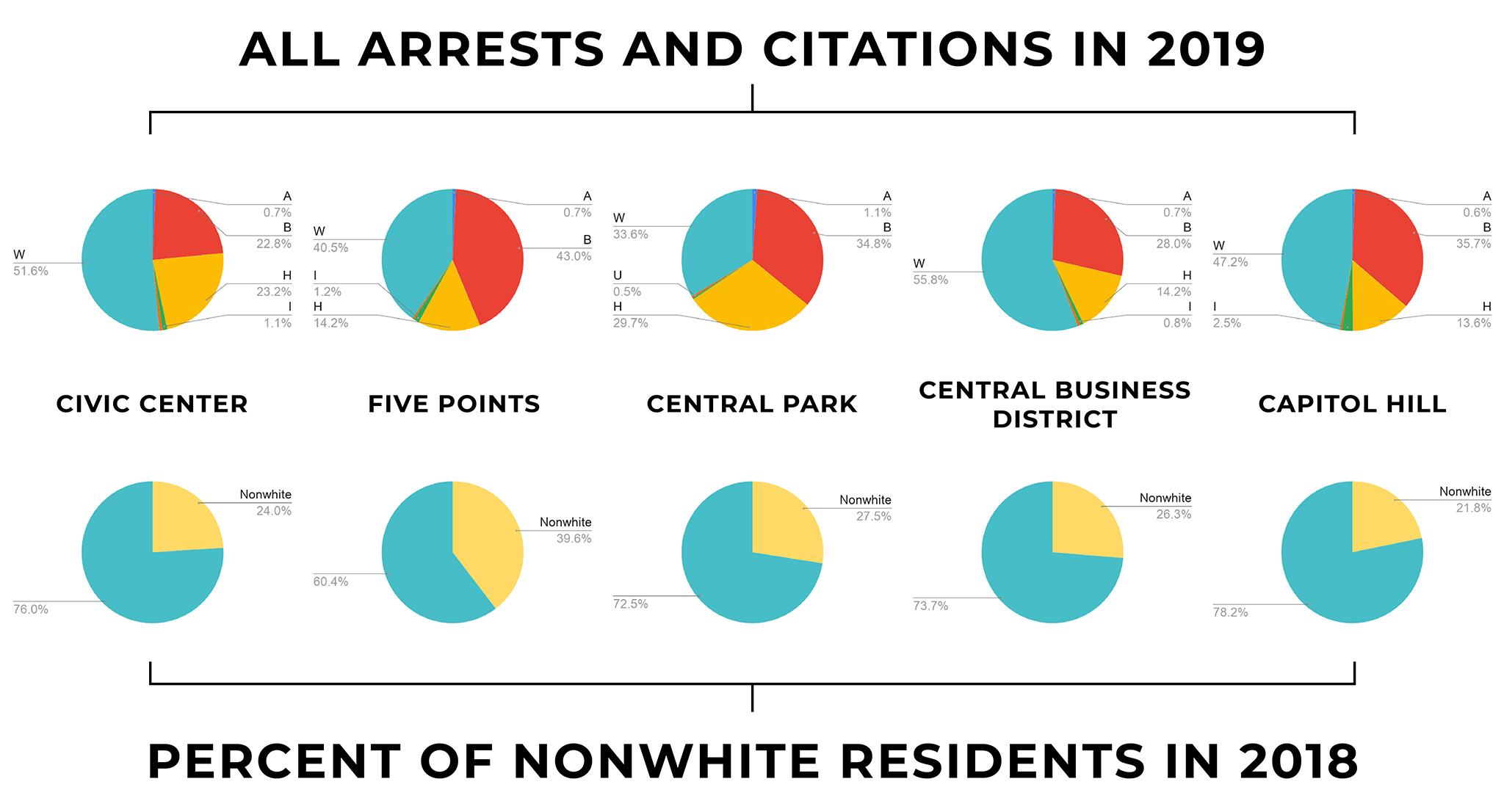

We also looked at the total number of arrests made and tickets given in each of Denver's neighborhoods.

Nonwhite people represented a greater share of citations than their populations in 11 out of the 20 neighborhoods with the most citations. These disparities were more pronounced in the five neighborhoods with the most citations: Civic Center, Five Points, Capitol Hill, the Central Business District (downtown) and Central Park. In Civic Center, where the most arrests and tickets were recorded between 2018 and 2020, nonwhite people make up just 24 percent of the population but made up nearly half of all citations.

Arrest data source: Denver Police Department. Population data source: City and County of Denver.

Durso and Namgung cautioned that this data does not signify causality.

Of course, the elephant in the room is racism in policing, but Namgung said that a slew of social, economic and geographic factors also play into why racial groups are disproportionately cited for crimes. He said racism in the broader community can influence these numbers when, for example, people call 911 and initiate police contacts.

There are also broader trends to consider. For instance, people experiencing homelessness account for about 40 percent of cases in Denver municipal court, and people of color are disproportionately represented among America's (and Denver's) unhoused populations. Someone's socioeconomic status can contribute to whether or not they are more likely to commit a crime, but poverty is tied to historic discrimination engrained in this city's very geography.

Racist policing can also not be ignored. On Wednesday, a University of Denver lab released a report on racial data gleaned from the Denver District Attorney's office. It had this to say about police: "While prosecutors were generally positive about their relationship with the Denver Police Department, they also pointed to policing strategies and behavior as disproportionately impacting communities of color and contributing to the overrepresentation of non-White defendants in the criminal justice system."

Researchers quoted one prosecutor on this matter: "I see where police focus their attention, and what they consider 'proactive policing.' You know, like, only doing drug stings along the Colfax corridor ... an area that's predominantly African American or Hispanic."

The report also says prosecutors felt some officers are biased in their work.

"I think for the most part, there are really good police officers in Denver, who are really good at their jobs and ... set a really high standard and really serve the community," one prosecutor told researchers. "It's sort of like the same names you see popping up and over and over, and you're like: This case seems a little weird. The stop's a little weird. Oh, it's this officer."

Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen said he's seen racial disparities in his own department's analyses of these numbers. But like Namgung and Durso, Pazen said there isn't an easy explanation.

"Disparities don't necessarily equal bias," he said. Still, he acknowledged: "We've got to do better, and I think that our team wants for us to identify innovative solutions, evidence-based solutions. We never want to arrest the wrong person."

One example of an "evidence-based" solution is a public safety model called precision policing.

For at least a decade, Denver police made an average of 50,000 arrests and citations every year, which Pazen said resulted from an "old-school, traditional" approach to "go in and over-police." In 2019, he directed officers to focus on busting people who had the potential to harm communities and find other ways to deal with people involved in less harmful crimes. For example, the department began deferring people contacted for low-level drug offenses to case workers instead of jails, part of a program called Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion, or LEAD. Pazen said the department recently expanded LEAD to cases involving shoplifting.

"There are folks that steal from grocery stores or convenience stores because they're hungry. Should that person be entered into the criminal justice system?" he said. "Probably not."

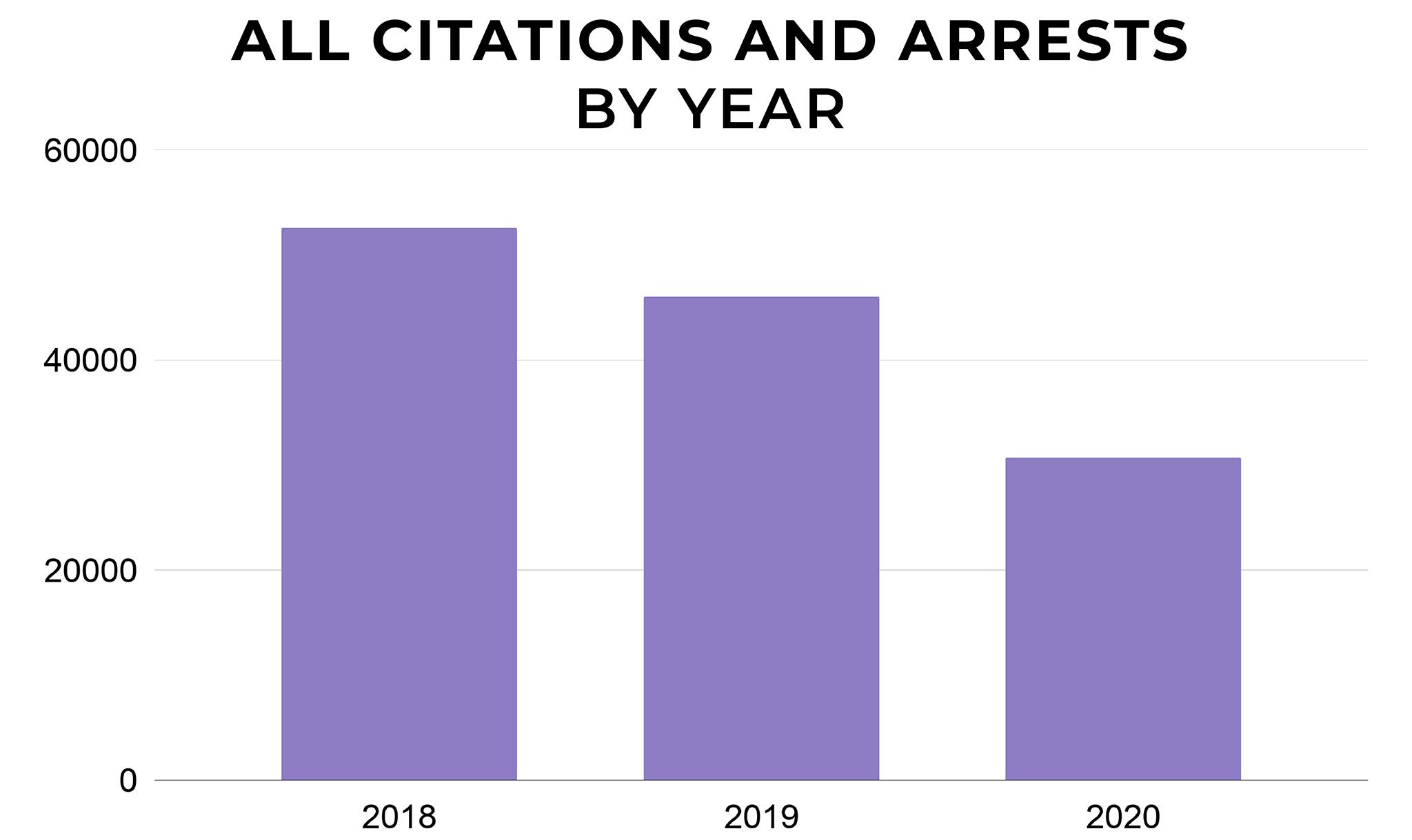

Department data show that the total number of arrests and tickets issued dropped between 2018 and 2020, from 52,595 to 46,046 to 30,696. (There's a big caveat on 2020's numbers, of course, since COVID-19 changed so much about which crimes were being committed and how police interacted with residents.)

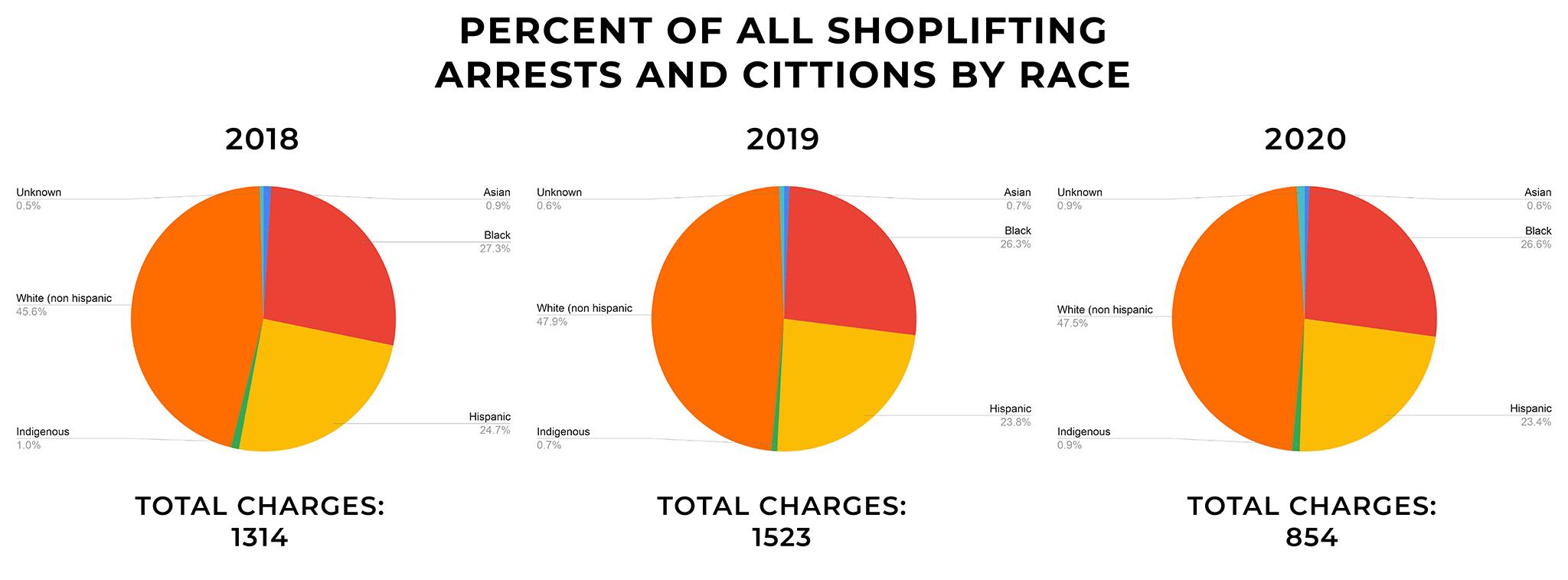

As arrests dropped, Pazen said Denver "maintained a relatively low crime rate." Still, the racial groups cited for many of the top-ten offenses remained constant. Shoplifting arrests, for example, dropped by 44 percent between 2019 and 2020, but Black residents received 26 percent of those charges in both years.

Pazen said collecting data on race is crucial as he works to improve the department and its relationship with residents.

"It's critical that we look at this. We pride ourselves on being a learning organization. We pride ourselves on working with the community. We pride ourselves on innovation and really trying to figure out how we keep our city safe and do it in an equitable way. You have to look at this data in order to do that," he said.

Namgung said police departments and the general public benefit from data collection and transparency. Inequities that previously came to light through hearsay and rumor can be rooted in fact, and data can give departments an opportunity to address problems in their work.

"For the past couple of years many police departments, including Denver's, tried to put that info (together) and make it public, and that's a good sign, for the researchers but also for citizens," he said. "Many people want to know what's going on in policing, what is going on in their communities."