Regan Linton, Phamaly Theatre Company's artistic director, is a "word person." She remembers trying to come up with a title for the company's upcoming show months back, shortly after it'd been conceived. She was looking for something that would succinctly convey the message Phamaly hoped to share.

For the past year, Phamaly, Denver's beloved theatre group for artists with disabilities, had been performing at a distance, rehearsing via Zoom and reaching community members through virtual programming. Linton said that when it came time for the group to put on its annual Vox Phamalia production -- a play, in sketches, traditionally built around the experiences of Phamaly members -- members wanted to do something special, to offer catharsis both to the tight-knit Phamaly and to its audience, who'd been kept apart for so long.

"We wanted to do a project that would bridge communities and connect people," Linton said. "Folks in the disability community have experienced unique isolation over the last year. So really doing a project that would amplify unique stories, connect people and highlight our artistry in a unique way during this very odd time."

"Vox," Linton knew, meant "voice" in Latin. She googled the word "corona" to see where it came from, and discovered that it's the Latin word for "halo," and the virus was named for the tiny halo of light that is visible when you examine the virus under a microscope.

"I just thought, that's so fascinating, that a virus, and something that has devastated humanity, still has this bright halo effect around it under the microscope when you look a little closer," Linton said. And so the show became CoronaVox.

"It was kind of representative of a voice emerging from the time of Corona, of COVID," she said. "I just thought that was very appropriate for our process of looking a little closer, digging into people and their stories. And that there's some light that comes from that."

Months later, CoronaVox: Stories from the Front, is set to debut May 3 to online audiences.

Sonya Rio-Glick, a Phamaly member and contributing writer on the project, said the show will be a COVID-19 spin on traditional Vox programs.

"Previously, Vox has been sort of a first-person sketch platform for Phamaly company members to tell our own stories with each other, or at least stick to sort of disability thematic stories," Rio-Glick said.

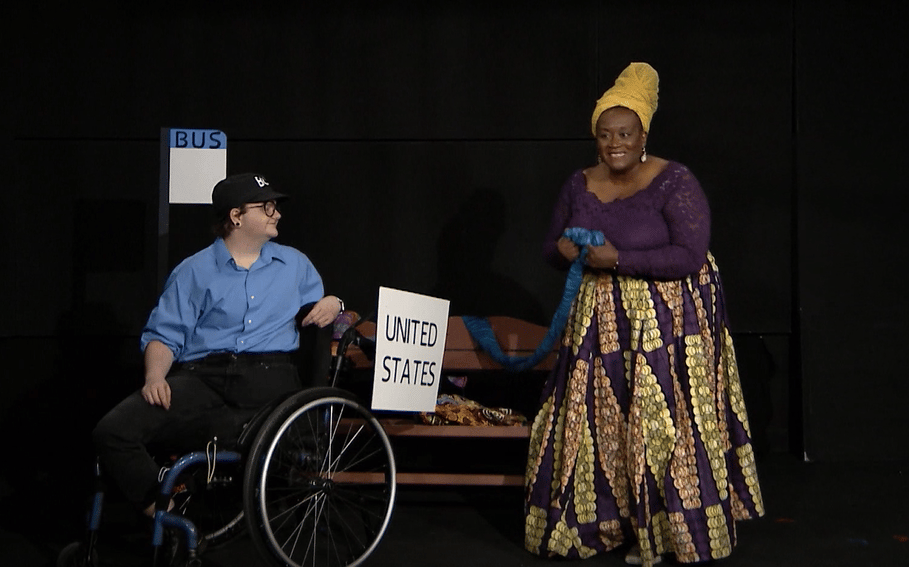

CoronaVox will be very different. This year, the company opted to step outside of itself and to highlight the voices of those who've been working to keep the community healthy and vibrant and functioning in the last year. Through partnerships with groups like Craig Hospital and the Denver Indian Center, Phamaly staged virtual interviews with Colorado frontline and essential workers to create stories based on their experiences during the pandemic. The stories were then converted into a series of individual sketches, each based on a different interview.

Rio-Glick, who wrote a few sketches for the show, said she worked to stay true to the stories that emerged from the interviews, almost acting as a documentarian. But she said other writers took a more abstract approach, incorporating songs or puppetry into their sketches. Linton calls the show an "eclectic cornucopia of pieces," each of which honors the interviewees' original stories and identities, even if not all of them recreate the stories verbatim. She said the show offers audiences space to reflect after everything that's happened since the pandemic began, and to think of experiences outside of their own, because every human has been impacted by COVID in some way.

"We're all human beings, when it comes down to it. We all have our own identities, but we're all made of the same materials," Linton said. "And I think that's a really important message to be reinforcing, is that there is this experience of shared humanity. And so how can we continue to use storytelling to develop that empathy between ourselves and other people, and find those opportunities to share each other's stories and therefore deepen our understanding of one another?"

CoronaVox will premiere virtually, but it was rehearsed and staged in person. The cast and crew were divided into three performance pods, each designated skits to write, direct, rehearse and perform, all while remaining distanced from other pods. Each story is acted out by a different, small group of performers, to limit the number of people onstage at any given time.

"I actually found the parameters to be really creatively inspiring," Rio-Glick said, "because I had to come up with new ways to set a scene up to minimize the amount of actors." One of the pieces she wrote, for instance, has a character who's only present via voiceover.

As a group made up of people with disabilities, Phamaly is particularly committed to making its shows accessible to everyone.

Rio-Glick said that moving shows to a virtual platform has, in some ways, improved their accessibility.

"There's not as many sensory triggers for folks who struggle to process multiple types of sensory at one time," Rio-Glick said. "And it works better for folks who need breaks, or just move through a process slower than other folks."

She says access provisions, like closed captioning and audio descriptions, are sometimes easier to provide over platforms like Zoom. And virtual performances also allow Phamaly to reach people who might not otherwise be able to participate. People with disabilities living in communities without many resources or programs have now had the chance to experience something like Phamaly. Rio-Glick herself has been living in New York. Because much of the show was planned over Zoom, she was able to participate in the project remotely.

Still, Linton said remote performance creates some challenges. There's the logistical concerns that come from coordinating schedules with people in different time zones. And there's the technical difficulties in planning a Phamaly show over Zoom.

"A lot of folks in the disability community don't have some of the technology resources," Linton said. "So, trying to navigate the ins and outs of somebody being on their phone, somebody not having speaker access, and trying to make it as accessible as possible."

But Linton said that even when Phamaly goes back to performing for a live, in-person audience, it'll likely continue to offer a virtual performance option.

"I hope that we'll continue to carry that forward," she said, "in terms of thinking from a more human-centric perspective, and not expecting everybody to fit into the mold of how we present our programs, but rather, how can we get creative with some slight tweaks and make this so that more people have access?"

Rio-Glick said that Phamaly, a rare disability-majority community, showed her what she can ask for in a work environment: that she can apply to write for a play in Denver while living in New York, or that she can tell someone when she isn't feeling well.

"I feel like sickness as a concept has become normalized, for better or for worse, in this time," she said. "Nobody knew the word immunocompromised except for immunocompromised folks a year and a half ago. And now that's in our language. And I think that sort of collective language about what it means to be fatigued, or ill, serves the disabled community and disabled artists. Because I still want to show up and work when I'm ill. I still can create. It just is going to look different than the traditionally healthy person."

Rio-Glick said each CoronaVox sketch is inherently different. Each conveys a different human experience about a different individual, as told by a different writer with a different style. Still, she says there are discernable common threads. There's a sense of joy and humor and the distinct flavor that Phamaly gives people.

"Something that unified the whole show, for me is the idea of perseverance, of, 'We're still here,'" Rio-Glick said.

CoronaVox: Stories from the Front streams from May 3, 2021 - May 30, 2021. Captions and audio descriptions will be available. Tickets can be found on Phamaly's website.