Paul Acuna had never seen anything like 2020. As general manager of the Romero Family Funeral Home, which serves many Latinx families in Denver, he had an intimate perspective on the tragedy wrought by COVID-19.

His workload more than doubled as he and his staff rushed to adapt to new and dangerous conditions. Each day that passed brought new clarity to the crisis unfolding in his community.

"It was a nightmare," he said. "It was happening. It was here."

In 2019, he told us, Romero helped about 600 families hold funerals, bury loved ones and find closure. That number rose above 1,300 last year. In the pandemic's second wave last autumn, he estimated at least one in three families who came in were there because a loved one had died with the virus. But there were many more that Acuna viewed as COVID-related, even if the deceased weren't infected.

"You were seeing the elderly dying of broken hearts because they couldn't see their loved ones," he said. "These folks were healthy, and they would wake up gone. They just couldn't handle it. Teen suicides were on the rise, not just with the pandemic, but with the riots, with all the hatred going on. And then gang-related homicides. So that's what we faced."

From difficulties accessing testing and vaccines to spikes in violent crime, there was a lot of disparate evidence that Denver's communities of color suffered more than white residents last year. New data from the state's health department put a fine point on what transpired in 2020.

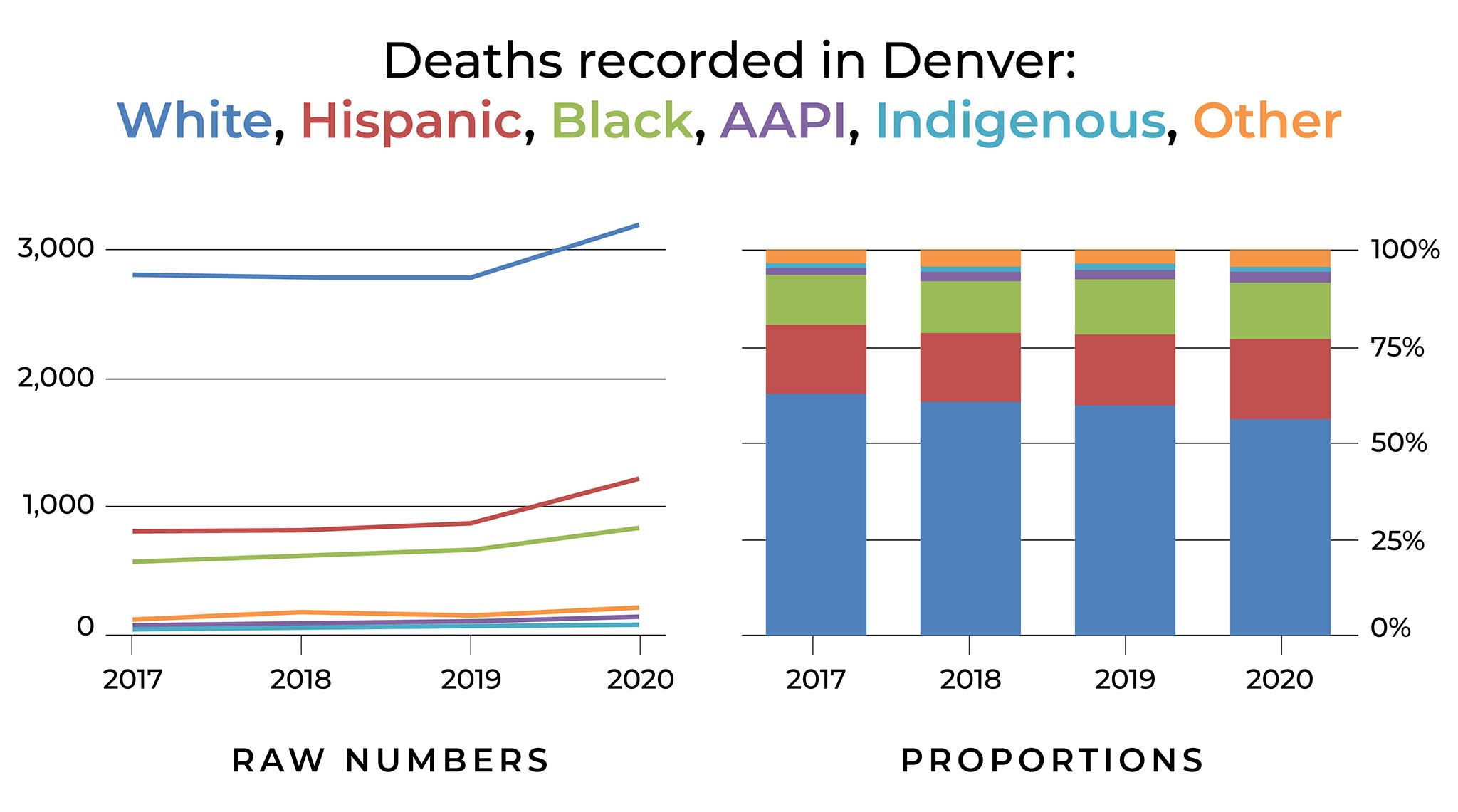

In Denver, deaths across all five identified racial groups grew in 2020, but a closer look suggests mortality rose faster in communities of color.

The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) gave us numbers that chart total deaths in Denver, not just those directly tied to COVID. While research shows Black and brown communities were more likely to die from the virus, these numbers demonstrate disparities in mortality on a broader scale.

CDPHE divvies people up into five demographic groups: white, Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander (AAPI) and American Indian/Alaska Native (Indigenous). Each death recorded can only be counted in one group. Some people (very few) are not included in any of these categories because they didn't fit into just one or their race or ethnicity wasn't identified.

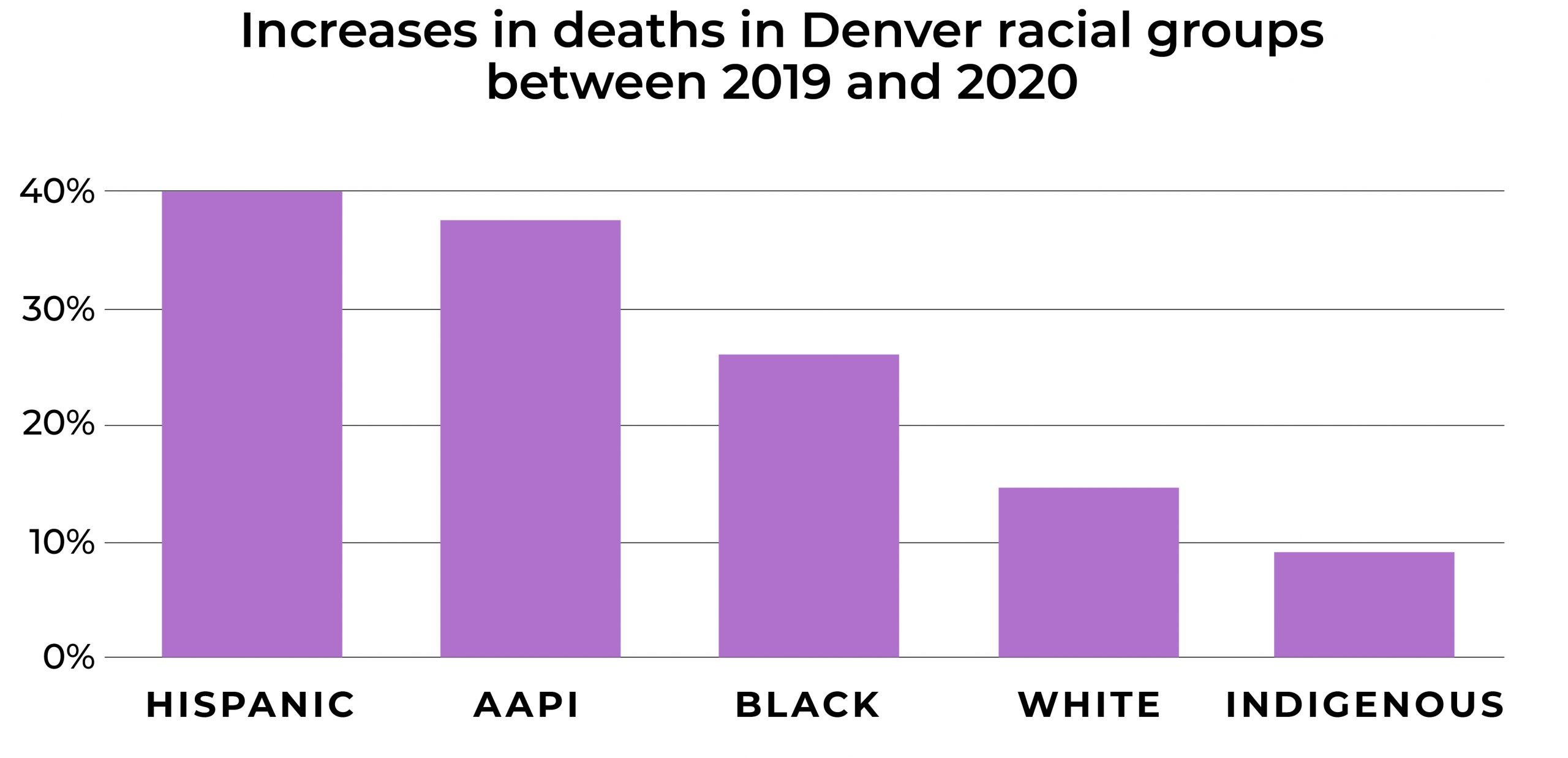

Between 2019 and 2020, deaths recorded among Hispanic residents grew the most of any group: a 40 percent increase, from 870 to 1,218.

Next were deaths among AAPI residents, which grew 37 percent, then Black residents (26 percent), followed by white residents (14 percent) and Indigenous residents (9 percent).

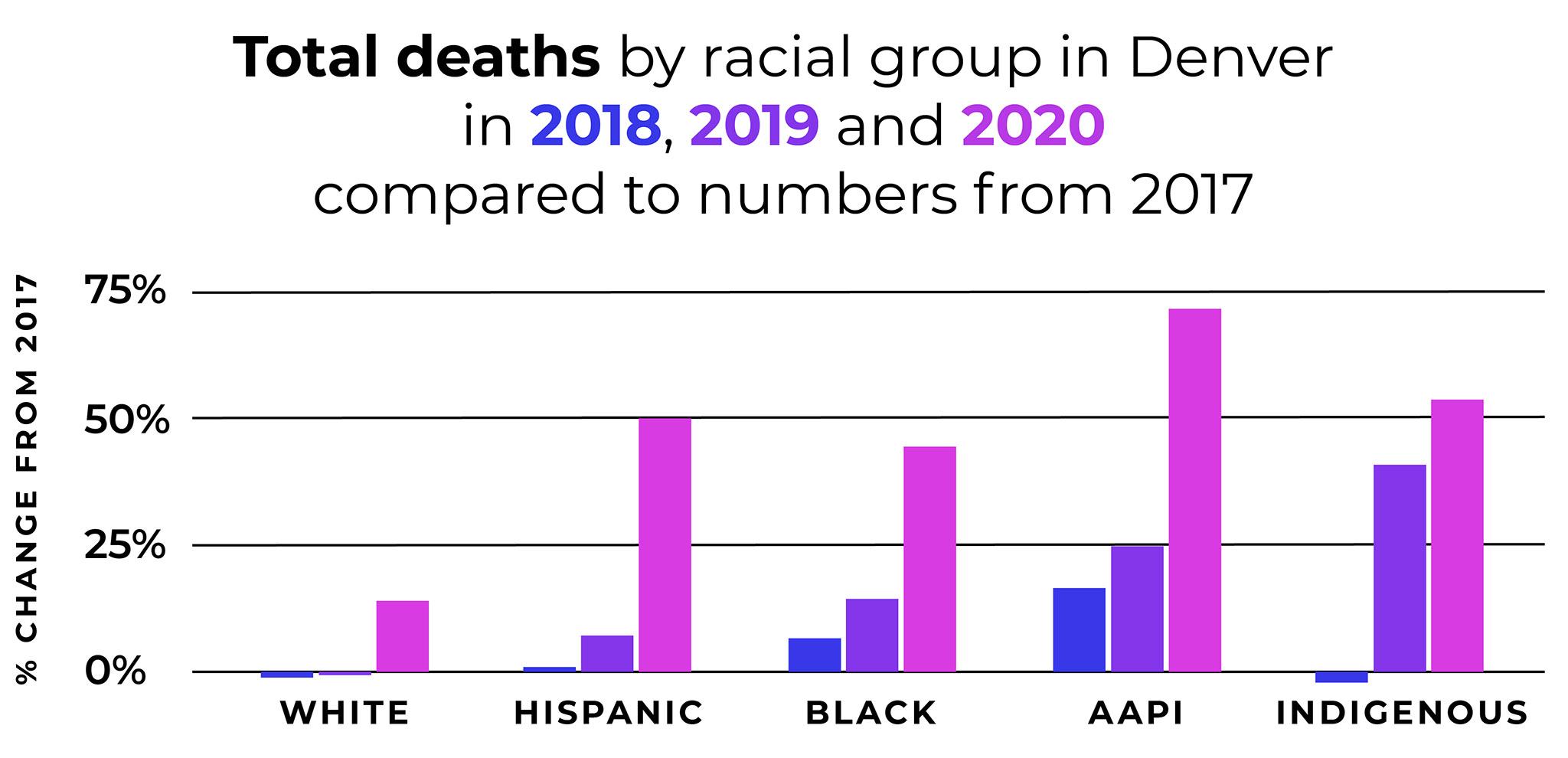

We don't have official 2020 population numbers yet, so calculating the exact death rate for 2020 isn't possible. But we still wanted to take a longer view. The following chart shows how many people died in each group in 2018, 2019 and 2020, using 2017 as a baseline.

You can see, for example, that fewer white people died in 2018 than in 2017. Also, population growth likely contributed to growing fatalities among Denver's Black, Hispanic and AAPI communities. Even so, it's easy to see how abnormal 2020 was.

(We need to note that deaths among AAPI and Indigenous residents were relatively low compared to other groups, which means small changes in the actual numbers can make a bigger impact on our analysis. To avoid presenting overly skewed data, we'll omit these groups from the last part of this analysis.)

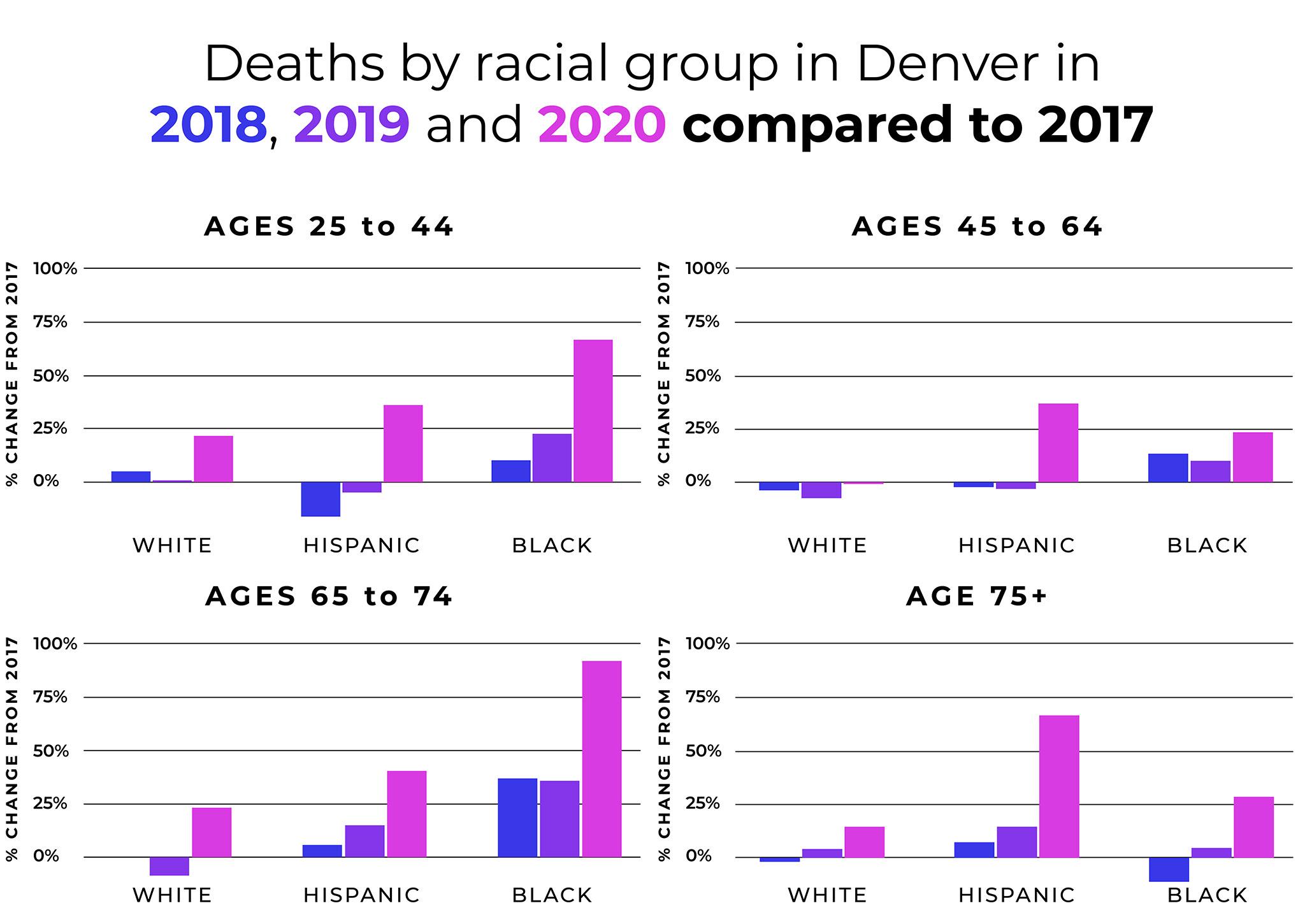

We also looked at how mortality rolled out across different age groups. For white residents, deaths among people aged 25 to 44 were up about 25 percent between 2017 and 2020. Deaths among Black residents in this age group rose 66 percent. There was also a large increase in deaths in the Black community among those aged 65 to 74.

Between 2017 and 2019, the number of deaths among Latinos ages 45 to 64 dropped, but they rose 40 percent between 2017 and 2020. Hispanic residents also accounted for a large increase in mortality for people older than 75, a 65 percent increase compared to 2017.

"Racism is real, and it impacts health," Dr. William Burman told us. "There's every reason to think that's a part of it."

Burman, an infectious disease specialist and the director of Denver Public Health, said it's useful to look into these overall numbers because the pandemic interfered with so much of "normal" life. New waves of overdoses, murders and suicides last year were all deeply intertwined with COVID's footprint on the city. So were the ways these tragedies affected families of color.

"I would argue that all of those were problems before COVID, but like so many things (were) exacerbated by COVID," he said.

Burman said racism plays into the kind of access a person gets to health care, especially since race and poverty are often linked.

"It's true of COVID, and it's true of other causes (of death)," he told us. "It's the whole litany of ways that race and income and immigration status all can interact to produce worse health outcomes."

Denver Public Health hasn't done its own analysis of overall mortality in 2020 (it's still laser-focused on the virus), but Burman said our findings track with research into disproportionate infection and death rates among Denver's Latinx community.

Funeral home workers who serve Denver's Black and Latinx families said the numbers back up what they experienced.

Tori Watts has worked in the funeral industry for about eight years, spending the last three as a family service manager for the Pipkin Braswell funeral home. Headquartered on Colfax Avenue, it serves many Black families in their time of mourning.

Watts said 2020 was extremely busy. They were burying two or three people a day, and she said it became hard to handle.

"It was just so many young people, and having to see so many parents heartbroken," she said. "Sometimes, we'd get two of the same family members within that same year. So it was a rough year for everybody."

Before the pandemic, Watts said it was normal to see causes of death come in waves. Car crashes might occur more in one month, followed by a period of violence. But in 2020, she said, tragedy was omnipresent.

"It was just all year. The numbers were just high all year," she said. "Towards the end of the year, COVID slowed down. But then it was overdoses. We had a lot of overdoses, vehicular accidents, gang violence."

For her, the reasons why were clear. Even if people weren't sick, lockdowns and unemployment drove people to risky behavior.

Acuna, the Romero funeral home GM, said people in his Latinx community had a hard time maintaining social distance. While many people of color hold jobs that can't be done remotely, he said strong community bonds were also difficult to break.

"You weren't going to tell a Latino family that they couldn't have a birthday party. You weren't going to tell them that they couldn't have family gatherings," he said. "They're so close and tight-knit."

Other factors played into the nauseating pace his staff endured. A spate of youth suicides gave him the impression that hopelessness surged last summer; it was something we heard from anti-violence activists in Montbello as the floor dropped out beneath many families in the neighborhood.

Much of the city is returning to some semblance of pre-pandemic life, but both Acuna and Watts cautioned people shouldn't let their guards down.

They've both seen too much to pretend life could ever be the same, but they've also continued to help families bury people who died with COVID-19. Acuna said he held services for a husband and wife a few weeks ago who died from the virus within a few days of each other.

"We're starting to see the COVID numbers go back up. We had even a 13-year-old lately that had COVID," Watts told us. "It's not over. I know people are happy they can be out in the world, but still be careful."

If there was one message she could send to officials and broader society, Watts said it would be to recognize the toll the last 14 months have taken on her community.

"I think there should be more awareness to the public," she said. "When do we connect the dots?"

The message for Acuna was a simple one: "Get vaccinated."

He came down with COVID last year. While he didn't need a ventilator, it hit him "like a Mack truck." He said everyone needs to understand that responsibility in this moment, so the weight of this health crisis can finally be lifted.

"I faced it head on," he said. "Now I'm vaccinated, so I can serve the community again."