Though activists, reporters and people living on the streets had said the pace of homeless encampment sweeps has reached a new high, Mayor Michael Hancock and his staff stuck to their talking point as they celebrated the opening of a new shelter this week: Nothing is out of the ordinary.

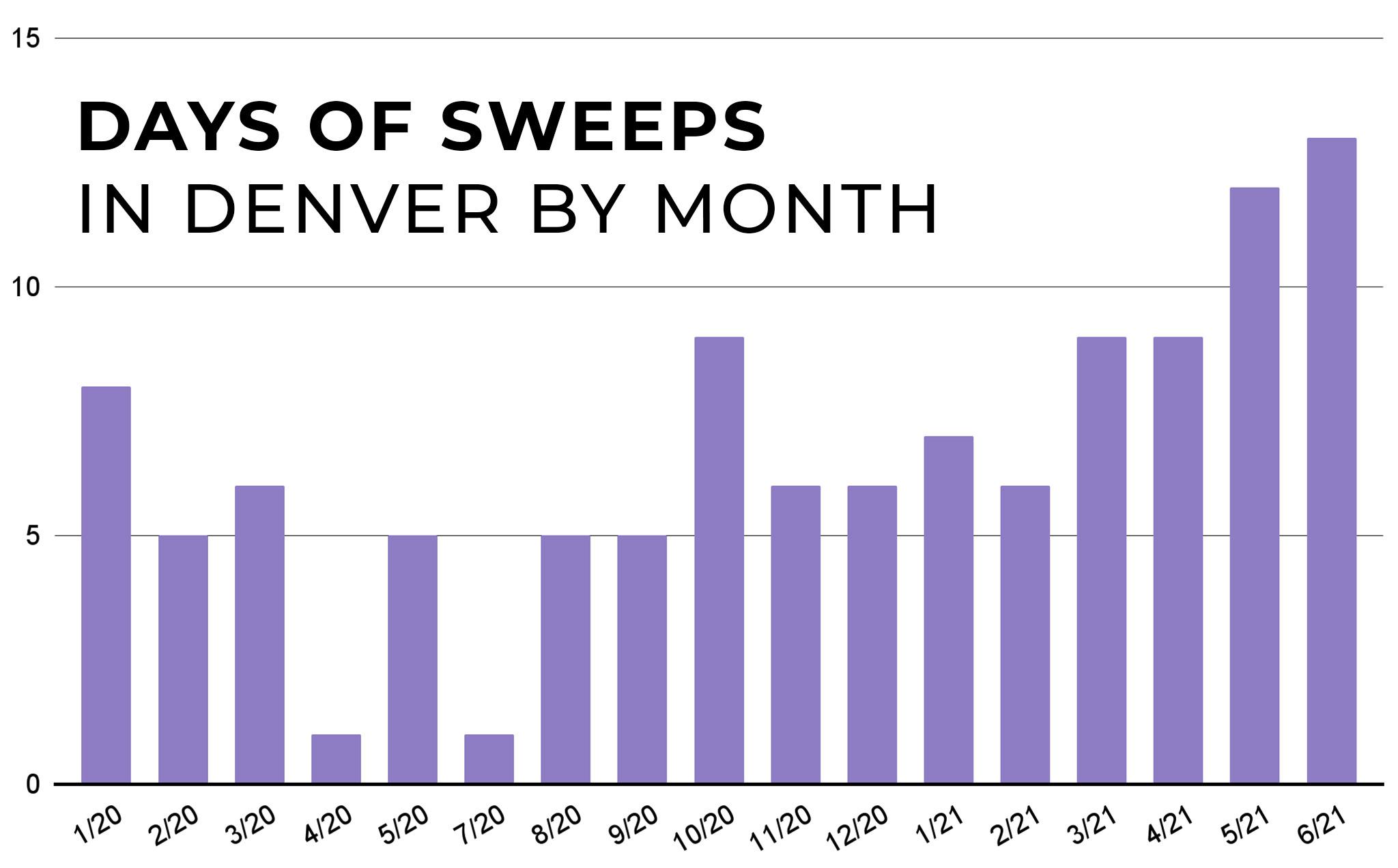

"No, this is not unusual," Evan Dreyer, Hancock's deputy chief of staff told us on Wednesday, as officials spoke to unhoused residents in a regular, court-ordered meeting at Civic Center Park before the press conference. "We were doing two, three encampment cleanups a week. COVID hit, we stopped. And we by and large didn't do any from March until the end of July, when there was a homicide at (Lincoln Park). Then, at that point, we kind of resumed where we had been, that same two to three a week. That's probably been the cadence for 11 months."

But documents suggest the critics were correct. City sweeps have reached new heights in recent weeks.

Denver has no central repository for information on these forced cleanups, so we had to rely on records requests.

We wanted to see how often sweeps take place and where they happen, so we obtained dozens of emails and documents from both Denver's Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (DOTI) and Department of Public Heath and Environment (DDPHE) to see what we could learn.

The paper trail really begins in January 2020, after DOTI started to notify City Council of upcoming sweeps. DOTI spokesperson Nancy Kuhn said the department has done this work since 2016, and they voluntarily began sending emails to Council around December 2019. In January 2021, a judge made these notifications mandatory.

DDPHE shared some documents that show it conducted public-health cleanups as far back as 2019, but its only done a handful and none this year. DOTI has conducted the vast majority of this enforcement since a judge declared the city's urban camping ban unconstitutional in 2019.

Though Hancock told press on Wednesday that ongoing sweeps were about "enforcing the laws of this city," namely the camping ban, none of the large-scale interventions since January 2020 were technically carried out under the ordinance. All of DOTI's notifications to City Council explicitly state the sweeps are "not enforcement" of the ban.

"We have an urban camping ban in the city of Denver, by law," Hancock said at the podium. "What we are doing post-pandemic is enforcing the law. And we have more encampments than we've had ever in the city of Denver, so we have more cleanups that we need to execute."

Here's what we found.

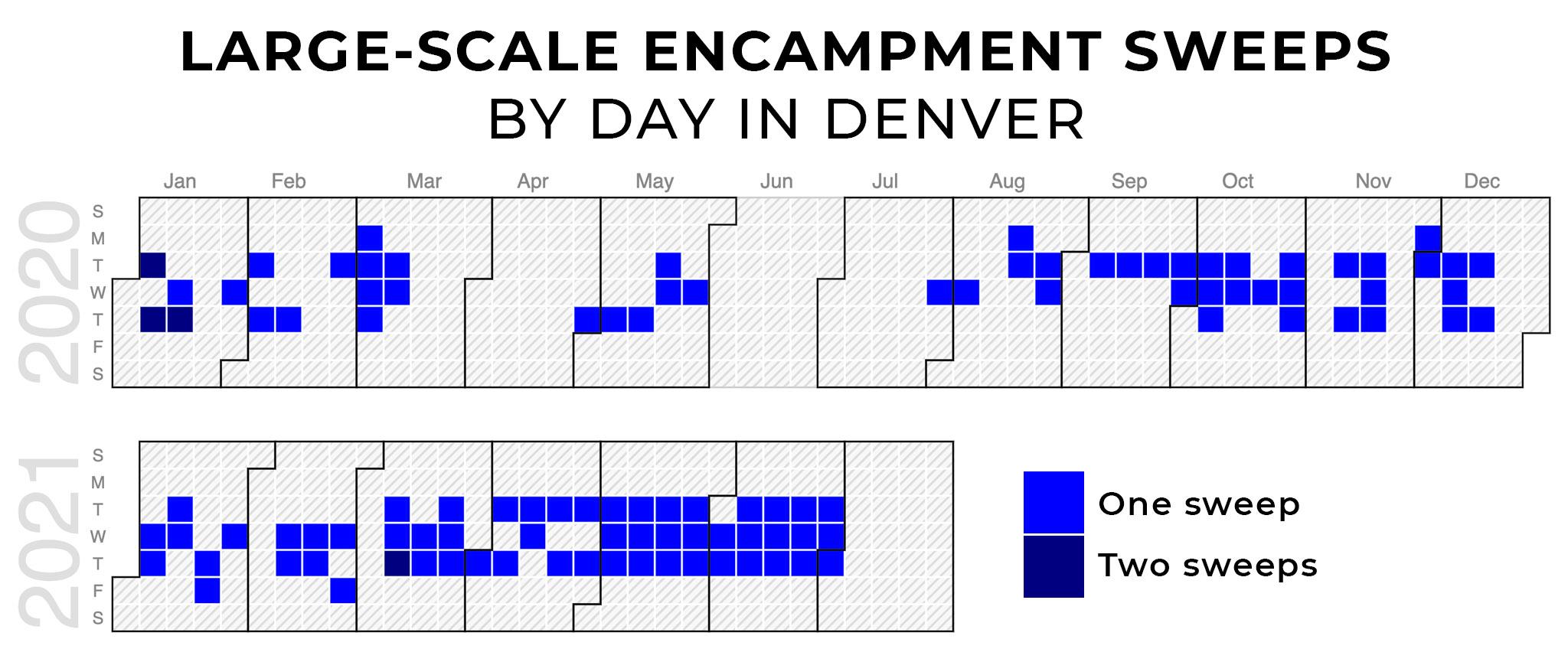

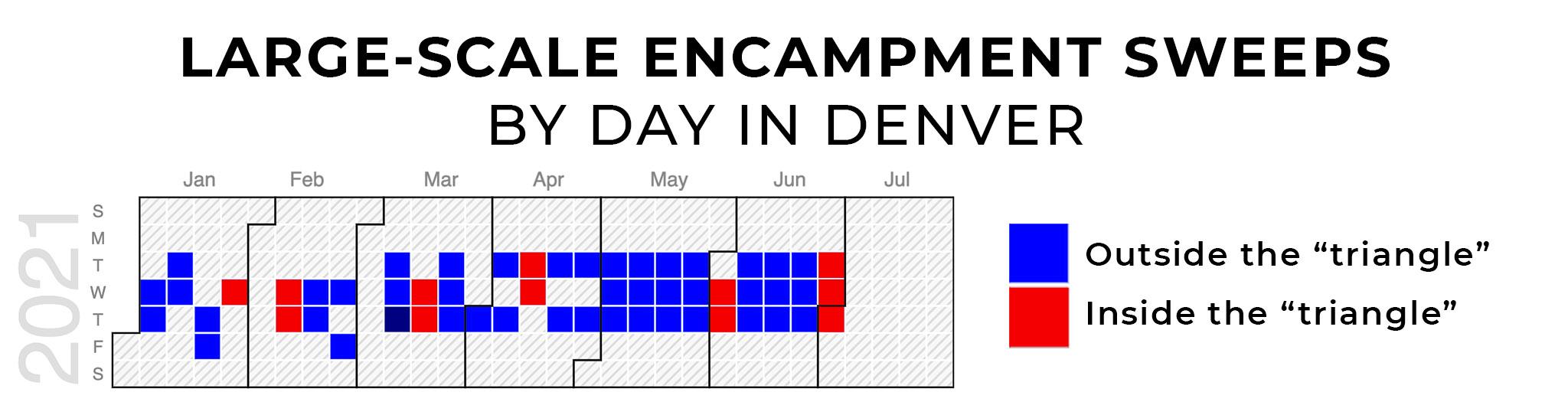

Records show officials conducted sweeps for 17 weeks straight since March 9, 2021, a streak unmatched since DOTI began sending notifications to City Council. There were more days of sweeps in June 2021 than any other month in this timeframe.

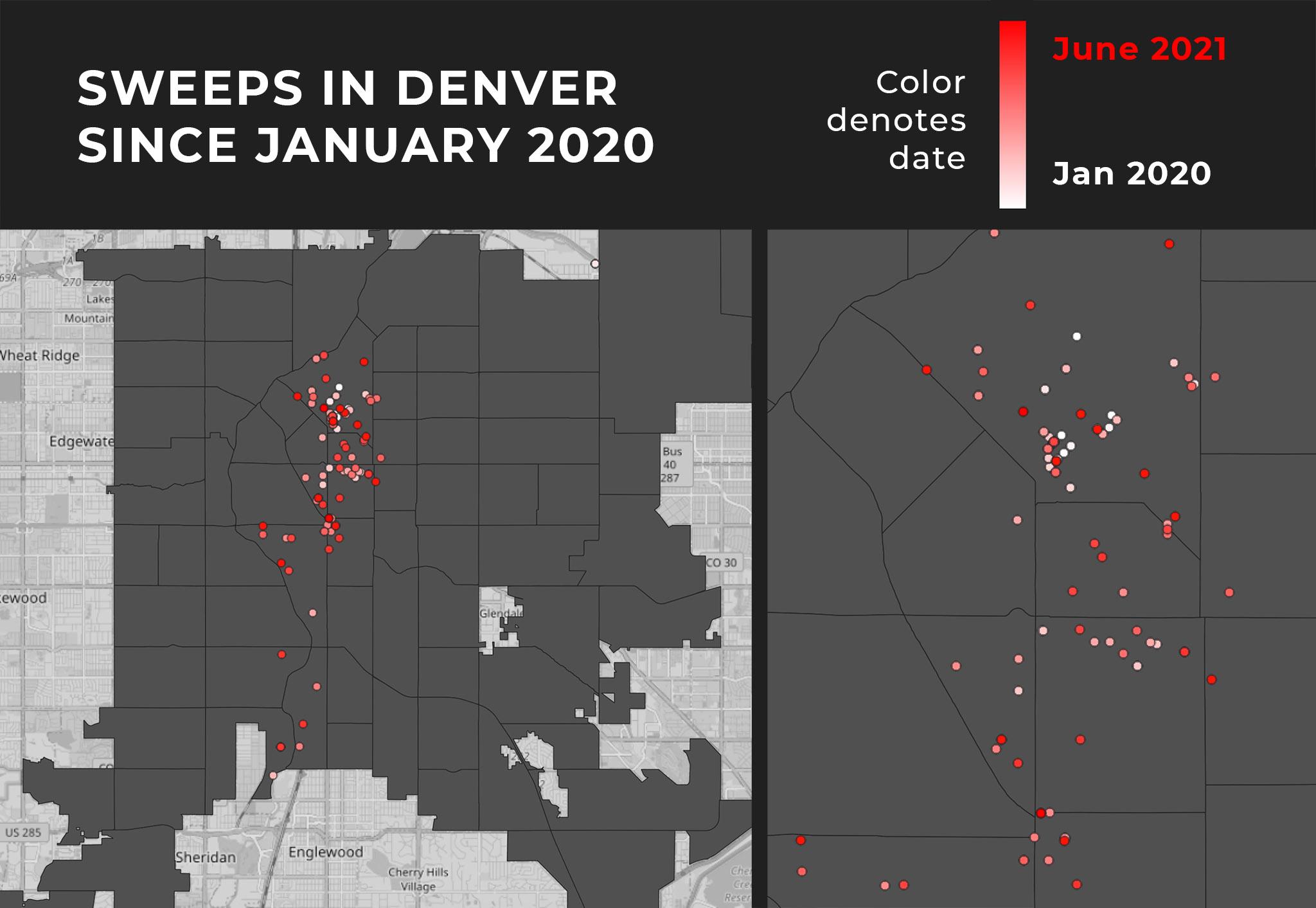

The records also show that sweeps are generally concentrated in the center of town and along the South Platte River. Early in 2020, these mostly took place closer to Five Points, where services and clinics are concentrated. Over time, the city began sweeping more encampments further out from Denver's center.

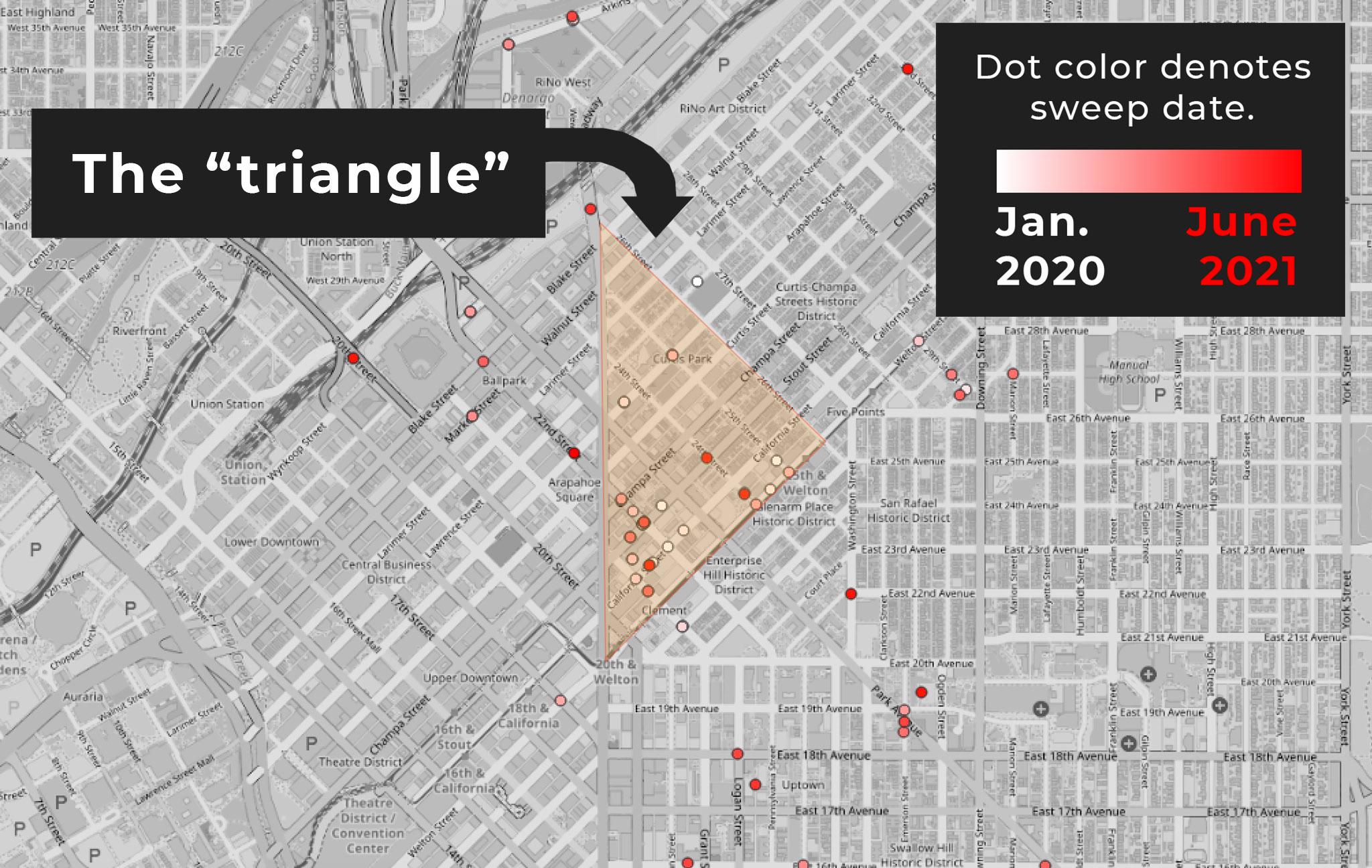

DOTI's crews have still continued to break up camps in Five Points, around the general area of 24th and Stout streets. John Staughton, a homeless rights advocate who has been campaigning against the sweeps, said people tend to scatter when large camps get taken down there. When they're swept away from smaller sites scattered around town, they usually gravitate back to Five Points.

"It seems to be, now, we're getting into a routine," he said. "They have a big camp, and then they bust it up, and that becomes six or seven smaller camps. Over the next few weeks, those camps get swept, consolidated, swept, and then eventually you get a big camp. Stout is often the big camp. It goes out and then it presses back in."

Source: DDPHE and DOTI

Of the 122 individual sweep days since January 2020 listed in city documents, nearly a third took place in a triangle of Five Points streets bordered by Broadway, 27th and Welton streets. Our analysis gives credence to Staughton's observations. In 2021, after things resumed from the COVID-19 hiatus, officials fenced off and ejected people living on sidewalks inside this triangle every few weeks, sweeping sites in all directions in between.

Other data collection simply doesn't exist.

When we spoke to Dreyer on Wednesday, we asked whether the city keeps track of how many people and tents are swept up each week.

"I don't think that's tracked specifically," he replied. "I've not seen it."

Kuhn, with DOTI, told us her agency doesn't track these numbers, either.

DDPHE's documents did contain some numbers. Over the course of eight sweeps, from Morey Middle School to the South Platte River, the department reported removing, storing or relocating 513 tents and removing 84 tons of "waste." Documents show workers also recovered almost 3,000 syringes in these eight events; almost half came from the massive camp that grew at Lincoln Park, across the street from the Capitol, when enforcement paused during the pandemic.

We also asked Derek Woodbury, spokesperson for Denver's Department of Housing Stability, whether his colleagues collect numbers on people connected to housing services during sweeps. He said teams of city workers regularly visit with people in need of housing, and that these efforts reached their "highest outcomes" ever in 2020, despite the pandemic. But he said hard numbers weren't available, with one exception.

"In May 2021, street outreach teams successfully placed 16 individuals into permanent housing. Approximately one-third of these placements involved individuals who previously were living in a large encampment setting," he wrote in an email. "I don't have anything additional at this time that is specific to street outreach at encampments."

In 2019, we reported Denver Police made at least 12,000 contacts with people related to the urban camping ban. Very few resulted in tickets, arrests or pathways to better situations. Denver Homeless Out Loud surveyed more than 500 people about these encounters, and found only 4 percent were connected to housing services.

Advocates are working to fill in the gaps.

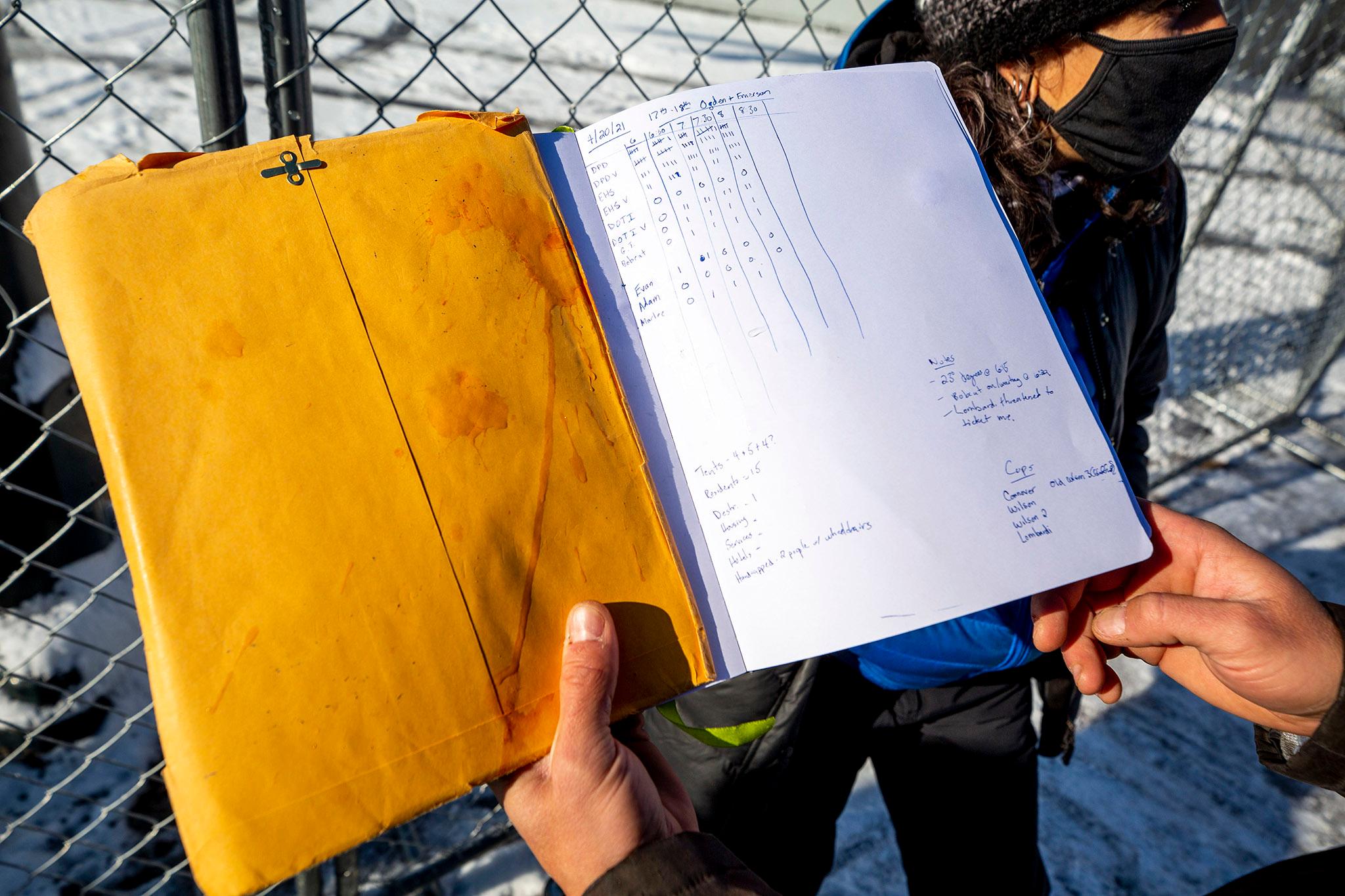

Staughton, who works with the advocate group From Allies to Abolitionists, said he was frustrated by this lack of reporting and started collecting his own data. On Thursday, he marked the end of a six-month audit period, in which he woke up at 4 a.m. to attend nearly every sweep in town. (Someone covered for him when he took two weeks of vacation.)

Each morning, he peered through temporary chain-link fences and scribbled observations onto a notebook or a form he and his colleagues created for the project. He collected numbers of police officers, police cars, social workers, tents doomed to removal and the people who emerged from them. He said Allies plans to write up their findings by the end of the year, a follow-up to a report they released in February. While his official tallies have yet to be compiled, Staughton estimated between 600 and 700 people are "caught up in this sweep cycle."

One purpose of the work, he told us, is an attempt to ballpark the cost of equipment and man hours that officials have dished out during his six-month watch. But he hopes the numbers might trigger some empathy in the general conversation surrounding the sweeps.

"I'm a sucker for giving people the benefit of the doubt, that if you give them information, they will be able to change their minds," he said. "You need to know that this problem is tragic and a crisis and really inhumane."

Social workers have told us cyclic relocation can make it difficult for people who live outside to access resources and can accumulate trauma that results in mental health crises.

John Listenberger, who was sitting on the side of Welton Street after he moved his camp from a sweep's fence line on Thursday, said his constant contacts with city workers left him stressed.

"I ask them, 'How would you like it if every couple days I come to you and tell you to move your whole (expletive) house? And you have an hour,'" he said. He didn't plan on going far: "This is my home. I don't care what the hell they do. They're not chasing me out of my home. Away from my family? Hell no."

Listenberger said he's been living outside for about six years, after he left prison with nowhere to go. He said he's been on housing waiting lists for about four and a half years. His story is not unique.

Hancock appears to be waving both carrots and sticks to solve Denver's housing crisis.

In his remarks at the new shelter on Wednesday, Hancock made clear he would not tolerate unsanctioned campsites.

"Unsanctioned encampments are not an option," he told the crowd. "While we must show compassion for our unhoused neighbors and provide them with dignified options, I stand here today to confirm my support for the city's unauthorized camping ordinance."

He emphasized that expanded shelter space, new housing projects, federal housing vouchers and Safe Outdoor Spaces are the real answers to the crisis.

"The aim of all of these steps and our entire strategy is to help as many of our unhoused residents as possible to enter housing and stay housed," he said. "We have never stopped trying to implement and bring different diversity and types of services to the people in this city."

Before Hancock's press conference, during the meeting between officials, activists and unhoused people at Civic Center Park, Denver Chief Housing Officer Britta Fisher fielded questions about how people actually access homes in the city.

Section 8 housing vouchers are hard to come by, she said, and her agency is hoping Congress will approve President Joe Biden's infrastructure package, which could include greatly expanded access to the program.

Right now, she said, "there's about one voucher for every four people who qualify, and so it's hard."

Hancock said he plans to use federal money and push for a bond measure in November that would allow the city to purchase motels where people can stay as they try to find more permanent places to live. Denver also currently has two Safe Outdoor camp sites, one in Park Hill and one at Regis University, but there so far are no public plans to expand the program.

Meanwhile, Fisher said the problem is worse than ever. Shelter use increased 54 percent in the last year. Currently 2,200 people sleep in the facilities each night, and about 8,000 people use day shelters around town.

"We are in the midst of a housing crisis that has been exacerbated by a pandemic. We are seeing more people experience homelessness than ever because more people are experiencing a crisis that results in losing their home," she said.

While people who live outside wait for something better, they must choose between shelters and dealing with ongoing sweeps. Some, like Listenberger, will choose the latter.

As the meeting at Civic Center Park concluded, Dreyer took the microphone.

"There's definitely an obvious tension here. Britta and her entire team are trying to do as much work as fast as they can to provide housing for people so that people do not have to live out on the streets," he told the group. "Until we get more solutions, more options that are acceptable to folks, the encampment cleanups are going to continue."