More cops and sheriff deputies, especially in certain areas, and crime “hotspots” in Denver, are the key components of Mayor Michael Hancock new plan to improve public safety amid an increase in certain crimes in the city.

“We’re going to remain focused on addressing these problems until they’re solved,” Hancock said during press conference Thursday, encouraging people who see something to say something. “It’s going to take the community to be engaged for us to make a significant impact on the challenges that we’re seeing.”

But advocates aren’t sold on what they see as some of the same old, same old approach to crime.

“I am disappointed to see us returning to the failed policies and practices that the global George Floyd protests were demanding cities move away from,” said Robert Davis, the project coordinator of a resident-led Reimagining Public Safety task force.

The task force gave the city “a roadmap to improving safety,” but Davis said Hancock and the safety department “have chosen political expediency over community solutions.”

During his press conference, Hancock warned about the prevalence of illegal guns, fentanyl leading to fatal overdoses, and people getting out of jail after posting bond and re-offending. His plans calls for 184 more cops by recruiting 144 new police cadets and recruiting 40 officers from other departments. It calls for recruiting sheriff deputies by creating a pipeline program with Denver Public Schools and focusing on retention. Mayor Hancock’s staff said the 2022 city budget includes funding for a class of 120 sheriffs recruits.

As the press conference concluded, Councilmember Candi CdeBaca, a frequent and vocal critic of the mayor, sent out an email with a subject head titled “Mayor’s press conf on safety-nothing new at all.” The email included a link to a video from a committee meeting from August 2021, where the city’s so-called crime hotspots were discussed by Denver Police chief Paul Pazen, who also spoke during Thursday’s press conference.

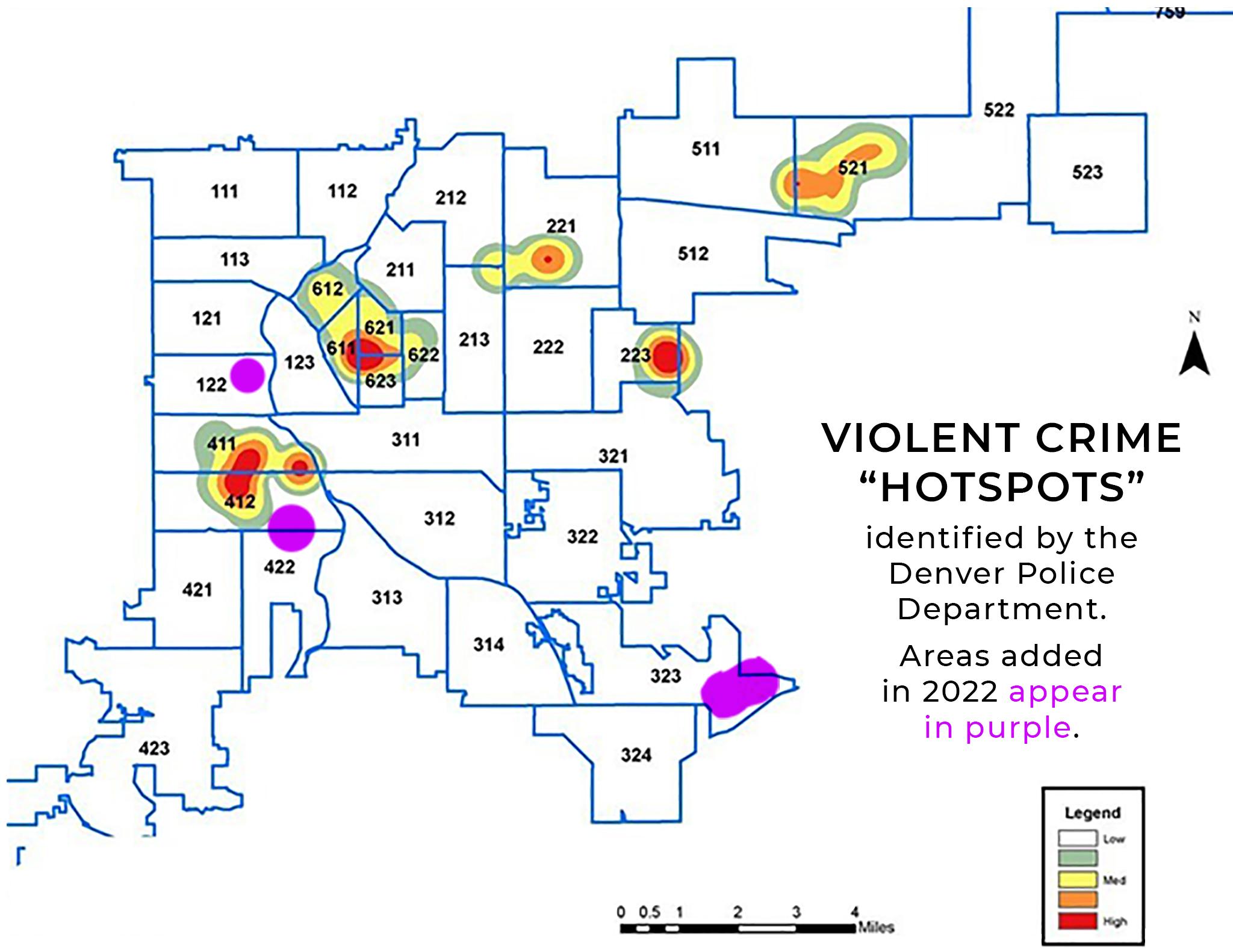

The city currently has five hotspots. Denver police define hotspots as areas of town that see the most homicides and shootings.

Under Hancock’s new plan, three more will be added. Pazen said the new spots will include:

- 14th Avenue and Federal Boulevard

- Mississippi Avenue and Lipan Street

- Dartmouth Avenue and Havana Street

In the August video, CdeBaca requested a breakdown of how much money the hotspot strategy costs.

Fast forward to Thursday’s announcement, and she noted the hotspot initiative isn’t new and questioned its effectiveness (Hancock acknowledged the strategy isn’t new). CdeBaca said the city isn’t doing a good job of tracking how much money is being spent to better understand how effective the programs are, or even how to measure the “success” of these programs.

“And hotspots is a new iteration of broken windows that disproportionately targets [Black and Indigenous people of color],” CdeBaca told Denverite via text Thursday.

Davis also expressed concern for hot spots, adding he wants to see strategies and programs developed alongside the people who live in those communities.

Focusing on hotspots works, according to Pazen and Hancock.

On Thursday, Pazen repeated a line he told lawmakers during the August meeting: A hotspot near Martin Luther King Boulevard and Holly Street had 17 shooting incidents in 2020 and zero in 2021, thanks to partnerships with the community.

Hancock said focusing on hotspots has led to a “dramatic” fall in gun and violent crime in those areas.

The police department is asking City Council for money to add more HALO cameras around the city. But CdeBaca and her colleagues paused the proposal because they felt they needed more information about the cameras, which the department uses to monitor certain streets.

“One clear trend apparent in ShotSpotter and HALO cam [conversations] is that we literally don’t have a clue how to track data/effectiveness on literally anything,” CdeBaca said.

Pazen said there was one more homicide in 2021 (96) than in 2020, but that was still enough to be the highest tally in three decades.

Shootings, burglaries, robberies and auto thefts have all increased, Pazen said.

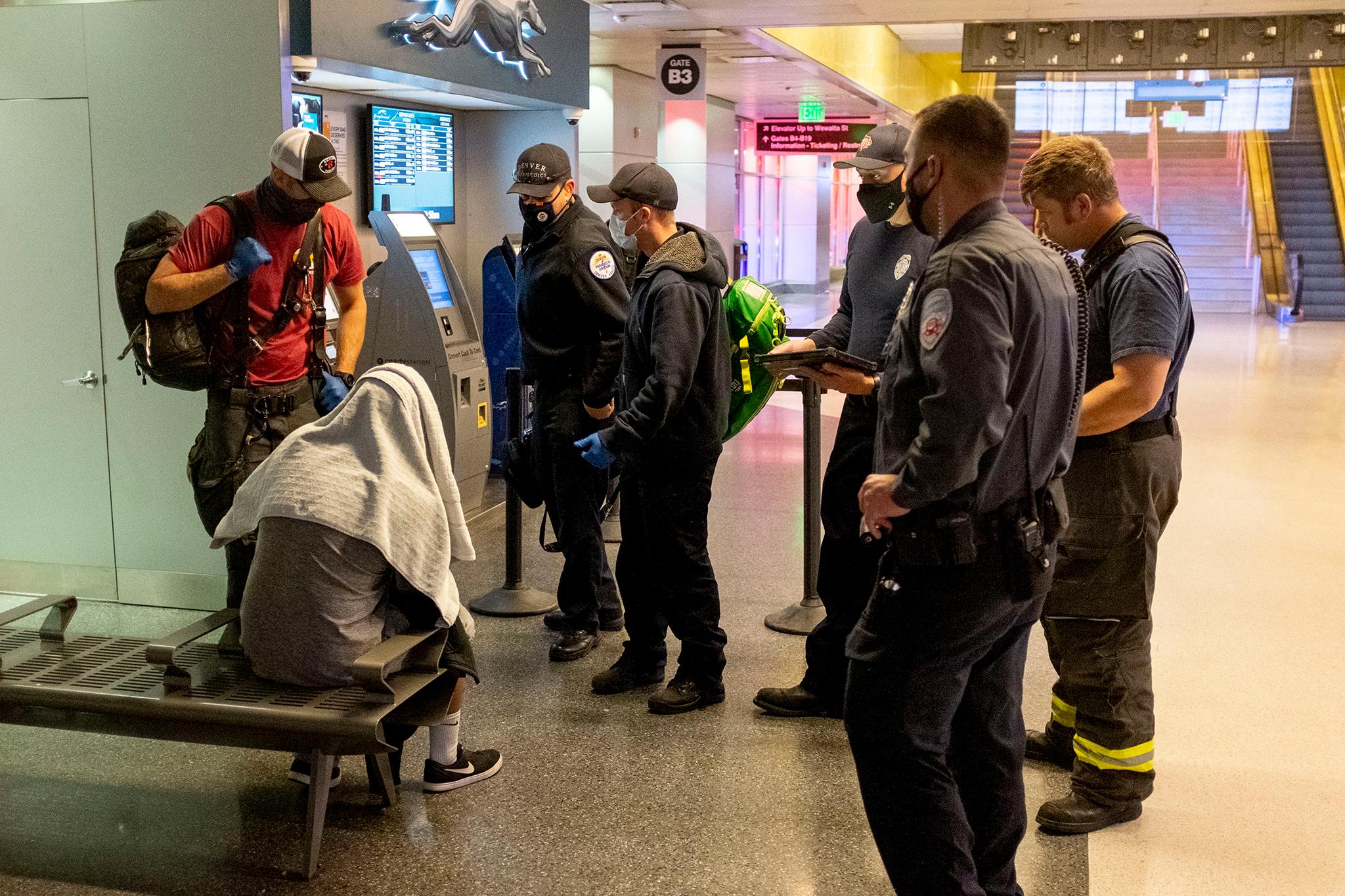

Union Station — branded “Denver’s living room” — has been spotlighted recently for its rise in crime there, though a closer look shows people who hang out there, including people experiencing homelessness, are trying to find a safe place to stay.

“The type of behavior, illegal behavior, that we are seeing at Union Station must be addressed,” Pazen said, without specifying the behavior.

Under Hancock’s new plan, enforcement efforts will focus on places like Union Station and the 16th Street Mall, both areas that see heavy foot traffic. Mike Strott, a spokesperson for the mayor’s office, said this will mean increased police presence and working with community groups and stakeholders. He noted these are all initial steps that could change depending on how things play out.

Pazen said the effects of the pandemic on crime will have to be studied over the next few years. He did note that narcotics-related homicides have increased: In 2020, only four homicides were related to drugs, while 15 homicides were drug-related in 2021.

“As we are seeing dramatic increases in fentanyl and methamphetamine use, we are also seeing this manifest itself in shootings and homicides,” Pazen said.

Lisa Raville, executive director of the Harm Reduction Action Center, has been asking the city for years to support an overdose prevention site, which she believes will help reduce public drug use and fatal drug overdoses. The sites give people who use drug space to do so under supervision.

She said she’s concerned with some of the Hancock’s plan to address rising crime, noting it doesn’t mention harm reduction. She said the city is experiencing a public health emergency that “demands” a public health approach.

Hancock’s plan calls for establishing an intake center that will connect people who need mental health or drug addiction treatment to resources 24/7. It’s an idea Raville said concerns her because it sounds like mandatory treatment after someone is charged for what the plan calls “disruptive behavior.” Officers and clinical personnel will evaluate whether to connect people with services, according to the plan’s description.

However, Raville said she’s had conversations with RTD and cops about harm reduction alternatives.

“Prohibition and criminalization have brought us fentanyl and other synthetic opioids,” Raville said. “Harm reduction initiatives increase public safety, criminalization simply does not.”