Last year, Regis University history professor Nicki Gonzales spoke with Denverites about the city's Chicano history. They weren't necessarily famous or notable residents. They were regular people whose family stories make up the rich fabric of Chicano history here.

Their reactions were the most rewarding part of a long process to catalog the stories for a new landmark report about Denver's Chicano, Latino and Mexican-American history, Gonzales said.

The faces of the people she spoke to would light up with excitement as they shared stories they weren't accustomed to sharing with anyone outside their own families.

"It wasn't written down, it wasn't in the mainstream and it was like people realized that their family mattered and it was part of this larger history of the city," Gonzales, the first Latina to serve as state historian, said. "And for me, I mean, I'm very much a people person and, and that, that's what it's all about for me."

Gonzales, who grew up in Denver and whose family is originally from southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, helped put together the unique project for the city.

More than a year after announcing the project, the city released the final report on Monday. Titled "Nuestras Historias: Mexican American/Chicano/Latino Histories in Denver," the 192-page report is just one piece of the entire project, which includes an interactive map highlighting historic places across Denver and a 31-minute documentary titled ¡Qué Viva la Raza! Honoring a Denver Legacy.

The report focuses on things like religion, education, labor, commerce, politics, arts, neighborhood life, and the Chicano Movement, a civil rights movement that fought for worker's rights, and equitable healthcare, housing and education for Chicanos.

Nearly 30 percent of Denver's roughly 715,000 residents are Latino.

Some of them, like Gonzales, can trace their roots back to present-day New Mexico and southern Colorado, while others are children of Mexican immigrants, or are second- or third-generation Mexican Americans, or identify as Chicano, a term that came into prominence during the 1960s. Some people identify by multiple terms; Gonzales, for example, identifies as Mexican-American and Chicana.

The report says Hispanos -- decedents from Spanish-speaking New Mexicans and southern Coloradans -- were already in Denver when gold was discovered in the 1850s, which prompted more to come to the city.

The report explains the various terms it uses when referring to the Latino population (it uses "Latino" as the all-encompassing term for communities that are Spanish-speaking or descended from Spanish-speaking people).

"So we really wanted to be careful that we were saying, 'Hey, we are not saying that this is just Mexican-American, this is just Chicano, this is just Latino,'" Senior City Planner Buddenborg, who led the project, said. "We understand that these communities are super-rich and diverse with their ethnic and racial connections. And so we really wanted to honor that and be upfront about that in the work that we were doing."

Buddenborg said more than 300 people in the city contributed to the project. The city held public meetings, conducted one-on-one interviews, and offered an online survey to let people provide feedback. From the start, she said the city was very intentional about making sure it reached out to Mexican-American, Chicano and Latino communities through different channels.

"We really wanted this to be from the voices of people within the Mexican-American, Chicano and Latino communities in Denver," Buddenborg said.

While the report includes well-known history, it also offers some lesser-known details.

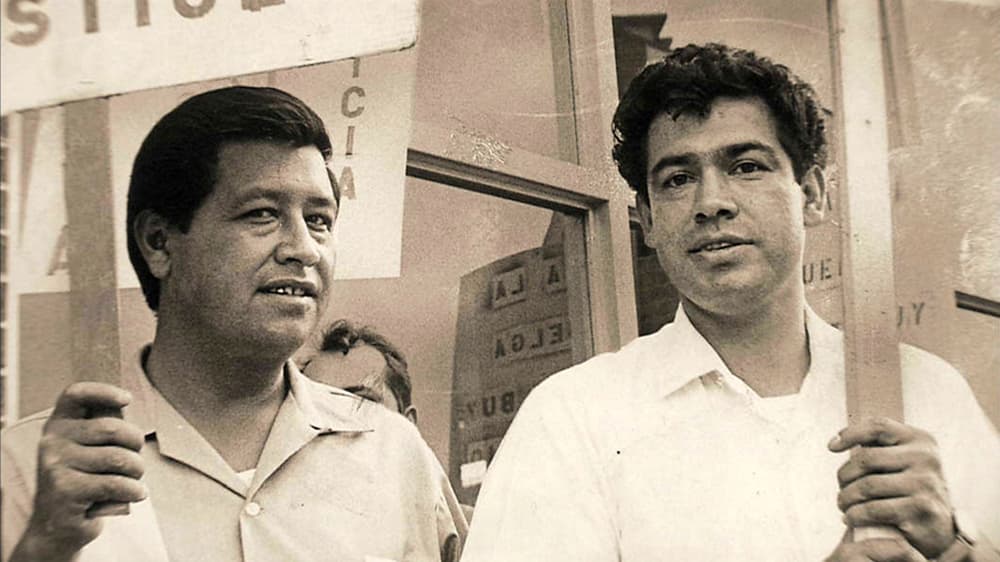

It notes familiar names like civil rights icon Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales; Federico Peña, Denver's first Latino mayor; Polly Baca, the first Chicana to serve in both chambers of the state legislature; and Rosemary Rodriguez, former city clerk and recorder and councilwoman. It highlights places like West High School, Smith's Chapel and Aztlan Theatre as places where Chicanos gathered and developed their identity.

Gonzales points to a home that once belonged to Lucy Lucero, at 547 Galapago St. Buddenborg said the house is still there, but the family who made it a special place isn't.

"It was open from like the 1950s to 2010 to young gay Chicano youth who had nowhere else to go, who were often kicked out of their homes," Gonzales said. "It's this really remarkable story. It was a place of food and music and drag queens, and just acceptance. And during the 1980s, during the AIDS crisis, they took in a number of young men who were HIV positive from the community, who again, had nowhere else to go."

"It was a safe haven, for young, gay Latinos," said Councilmember Jamie Torres, whose Westside district has a large Latino population and is featured heavily in the report. "I never knew that."

The document will be used to help preservation efforts.

Denver has hundreds of landmarks and numerous historic districts claiming a special connection to the city's history, but the majority highlight contributions made by the city's white residents. Buddenborg said only about 4% of the city's 7,200 historic properties are connected to minority communities.

"So we're not really telling full history," Buddenborg said. "That was really a big push of why we did this project is that we want to ensure that we're not just representing the white male history of Denver, that we are representing the total, rich fabric that the city really has, and that makes it unique and makes it what it is."

Buddenborg said Councilmember Amanda Sandoval, whose father Paul Sandoval was a prominent Chicano politician, is working to make La Raza Park a historic landmark. Torres is exploring a similar option for the Aztlan Theatre. The report will also be used to inform the area plans that help guide how neighborhoods should grow.

Torres, who identifies as Chicana, said she doesn't want the project to become an archive: "It should be living, people should still add to it."

Buddenborg said there are plans to use the report's findings for walking tours led by Historic Denver and Denver Architecture Foundation this summer.

The report might be done, but Gonzales wants to keep working on collecting the city's Chicano history. She wants to get grant money to write a comprehensive history of the city's Latinos.

"I was so moved by the number of people who, who just wanted to tell their story," Gonzales said.

Editor's note: The report misidentified Lucy Lucero's first name. We've fixed the error in this story.