Two years ago last Saturday, a then-editor at Colorado Public Radio, Kate Schimel, addressed our newsroom and told us to buckle up. This novel coronavirus we'd all been hearing about on international news had arrived in the U.S., and it was only a matter of time before it would impact everything. In the weeks that followed, my stomach somersaulted as we rollercoastered through some of the strangest months of our collective lives.

This pandemic is not over, but now we have some distance to think about how odd things were when everyone was just inside. When my editor asked me to pull up a bunch of photos from that time, I decided I wanted to use the opportunity to meditate on how it felt.

Our newsroom meeting took place on March 12. Some of us, myself included, wondered how big a deal this actually would become. The whole city couldn't shut down, right?

That afternoon, I went to the Capitol to take photos of a virtually empty building that was about to indefinitely suspend business. The next day, I visited Carson Elementary School, where kids were preparing to leave for an extended spring break; everyone thought they'd be back in class before too long.

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Then, less than a week later, I took a photo of a barren 6th Avenue at rush hour. It was a moment when the gravity of the moment really started to sink in. It wasn't long before I was photographing empty restaurants, to-go-only lines, mutual aid efforts and deep cleans.

To be clear, Denver never completely "emptied." Plenty of essential workers were still around, people ran errands and I grumbled about photo stories that purported to show cities as ghost towns. Still, this place had become wildly different. But I don't need to tell you. You lived it, too.

I get a very specific pang in my gut when I think back on it now. It's part queasy, part panicked. It smacks of existential dread and wrenches with a loss of control. I wonder if I felt that way nonstop, or if this is some memory of my worst moments.

That feeling is something I wanted to understand better, so I spoke with Dr. Carl Clark, psychiatrist and Mental Health Center of Denver CEO, to dig into it.

Clinically, Clark told me, what I felt in 2020 was simply stress. But he said it was a variety of unease that we haven't felt on a societal level in a very long time.

"When we feel stress, our natural instinct is to come together as people and support one another. And so this happened and what were we told? Stay at home. Be alone," he told me. "It went against our natural instincts."

It went against our natural instincts. I think this is an obvious point, something I knew all along. Still, the words struck me in a way I didn't expect.

Without our usual pathways to peace, we looked for whatever we could use to cope. Not all of the things we found were healthy choices.

Clark noted 2020's alcohol sales rose well beyond the norm; that showed up in a big way during the great, short-lived Denver prohibition of March 23 when people thought liquor stores would close and lined up for hours to stock up.

Weird circumstances: check. Weird responses: check. That'll hit your gut in a new way.

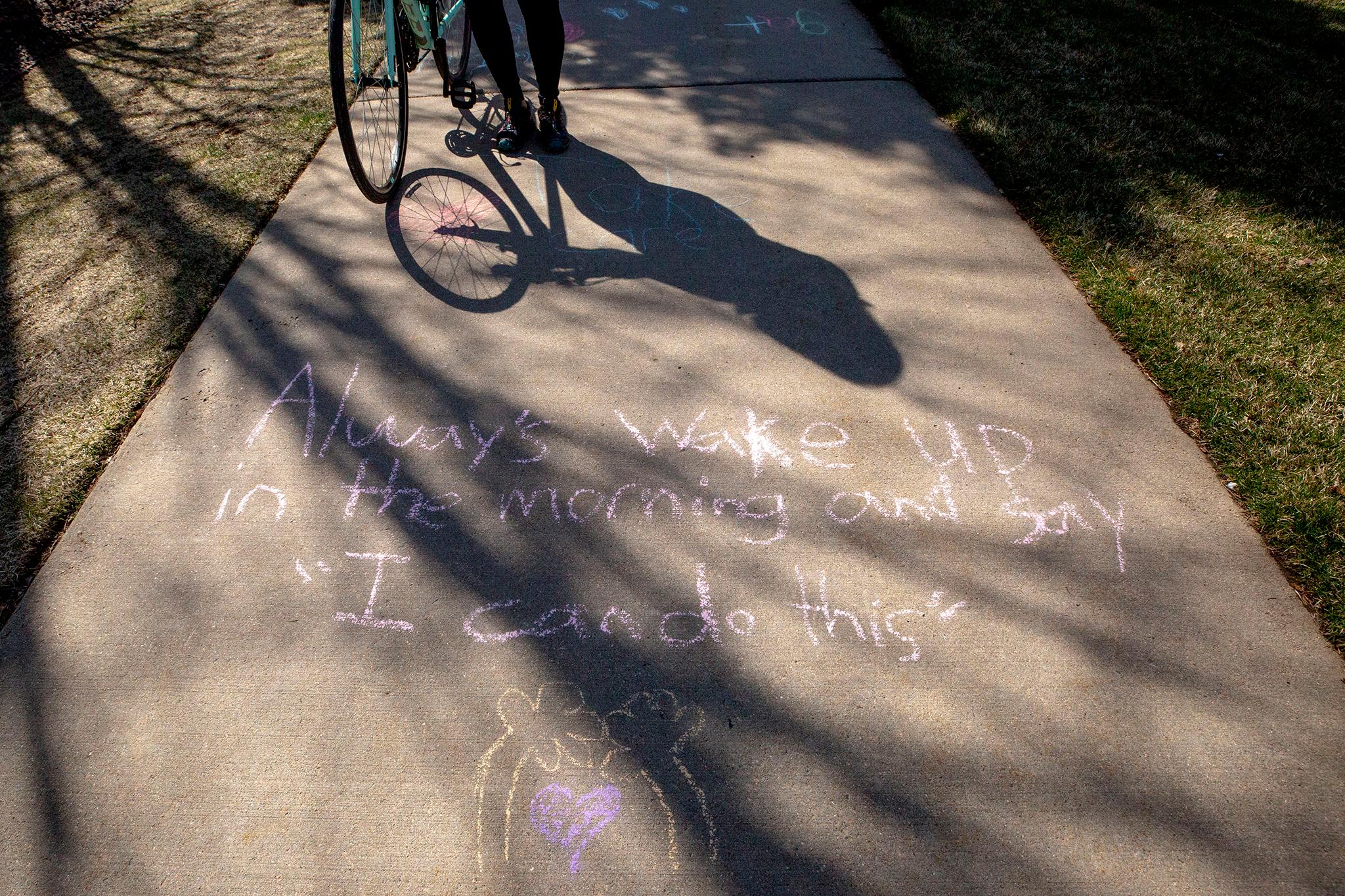

But we also found plenty of healthy ways to deal. We gardened, we baked. We binged Tiger King. We became runners and knitters.

We were isolated, but we also had lots of ways to communicate - and we discovered that so many of us were turning to similar tactics to feel sane. That, I think, contributed to the oddness of the moment.

I'll never forget a comic a friend of mine sent me. It depicted a few scraggly people on a life raft, lost at sea, and one of them says something like: "I'm working on my novel!"

Beyond the obvious pressure sources, Clark said each of us affected each other as we sought to make sense of it all. We radiate emotion.

"We're actually very much more interconnected than we even might be aware of. When you're well-being is good, you have a ripple effect on the people around you," he said. "It actually improves the well-being of people around us. Now go the opposite direction."

Clark said researchers have determined that negative emotion generally creates smaller ripples than positive feelings. Still, the pandemic's unique global and isolating nature reverberated in a unique way. Our connections, be they online or spaced out during parking lot picnics, changed us further.

Clark also said new ways of radiating emotion had very specific downsides. It was too easy to become siloed in to self-selected channels, especially in the context of social media. Our fractured communities were more prone to become echo chambers, where conspiracy theories and ill will could fester. It didn't help that we, as a society, were moving through stages of grief.

"Denial, anger, bargaining," he said. "We would see that kind of language in how people talked to each other every day."

Here's the thing: I hope there's some way to actually preserve that pit-of-the-stomach sensation that I still get when I think about 2020. I want us to remember how "unprecedented" everything felt (try to tally how often you heard that word used).

On one hand, those early months of lockdowns and uncertainty represent a rare moment of bizarre camaraderie that, I think, deserves preservation. On the other, it might help us down the line.

There are some reflections on the 1918 flu pandemic that call the catastrophe a "forgotten" era, a moment of medical chaos that was largely lost to time until we faced something similar again. I read a few articles that pinned an ensuing global war on the event's omission from our collective history. Another said there just weren't enough stories told about individual families struggling during that time.

I hope these kinds of events don't become more frequent, though there's some concern they will. But if humans wait another century to experience this again, I want the meantime generations to have some sliver of understanding of what we went through together. It could be a historical oddity. Then again, maybe that recognition will force them to be better prepared than we were. Maybe that future society won't freak out and buy all of the world's toilet paper at once?

And there's one more thing: Clark said we could be in danger of suppressing the last two years. It could be a harmful reaction that he and other mental health experts are working to deal with one patient at a time. COVID-19 impacted each of us differently, but his advice is the same to anyone still trying to push their feelings about it into the shadows.

"Confront it, and confront it head on, and allow yourself to really, deeply experience what you experienced," he told me. "Re-understand it, in a way that helps."