We recently wrote about an effort to save a home in Skyland once owned by Charlie Burrell, the "Jackie Robinson" of music who was one of the first Black performers to work for a major symphony orchestra in this country. While his old neighbors want to see the house preserved, his family is not so attached to it.

Instead, Purnell Steen, Burrell's cousin and fellow musician, said Denver should try to designate another home as a landmark: one in Whittier built by musician George Morrison in 1921.

"He was to Denver jazz as Louis Armstrong was to jazz in New Orleans," Steen said.

After that story ran, we heard from Whittier residents who have already begun a process that might protect Morrison's home. Gary and Joanne Goble, who live across the street, said they attended their first meeting with the city to see if they can turn part of Gilpin Street's 2500 block into a tiny historic district.

Both Gobles worked for the Colorado Symphony, where they were coworkers with Burrell. But their interest in the block actually begun with the architect of their home, David W. Dryden, whose first projects were a handful of homes on Gilpin Street. He'd later take on larger projects, like North High School and 22 other Denver schools.

"We've all along thought about whether a historic district would make sense," Gary told us. "Now, we're both retired and have a lot of time. It seemed like something we should start doing."

Joanne said she and Gary always knew about Morrison's presence on the street, and they've included his legacy in their initial proposal.

To successfully create a historic district, they'll need to prove elements of the block have significant ties to historic events, people or movements; show outreach to and approval from their neighbors; pass a Landmark Preservation Commission hearing; and receive final approval from City Council. The meeting they had with officials a few weeks ago is just the beginning of a long process.

A little more to know about George Morrison:

According to articles we found at the Denver Public Library, he was born in Fayette, Mo., in 1891 and moved to Boulder in 1899. He came from a family of musicians, and told jazz historian Gunther Schuller that all the Morrison men who came before him were fiddlers.

"In those days, instead of violinists they called them fiddlers," he said in the 1962 interview.

He grew up with a hunger to play music, but -- his 1974 Denver Post obituary read -- "he wasn't allowed to use his father's fiddle." Instead, he'd build his own.

"I would go out and take a corn stalk and hollow it out. I would take a knife and cut the stalk in four strips, and then I'd get me a little piece of wood and put some cord strings on there. I'd tighten them up myself," he told Schuller. "I was about five years old when I was doing that. Then later, as I grew older, I made my violins out of cigar boxes."

When he still lived in Missouri, Morrison said his family would wander with instruments at night, serenading neighbors who'd throw money down from the windows. The Morrison Brothers String Band, as they called themselves, would later tour the Front Range, playing for miners in camps and fraternity boys at the University of Colorado. When he played with his family, Morrison played the guitar.

While he told Schuller he was truly "making a living as a musician" in his youth, he also held down jobs shining shoes and working as a gofer for Boulder barbers. That extra work gave him the capital to buy his first violin and take lessons from a trained musician.

As he progressed, he became the pupil of professor Howard Reynolds, an old-timer from Boulder and New England Conservatory alumnus who charged Morrison 75 cents per hour for lessons two or three times a week.

"I was his only Negro pupil," Morrison said.

Morrison competed with all 42 of Reynolds' students for support to attend the New England Conservatory and won, though, according to his obituary, he could not accept the scholarship. He'd later attend a conservatory in Chicago, which launched him into a new echelon of performance.

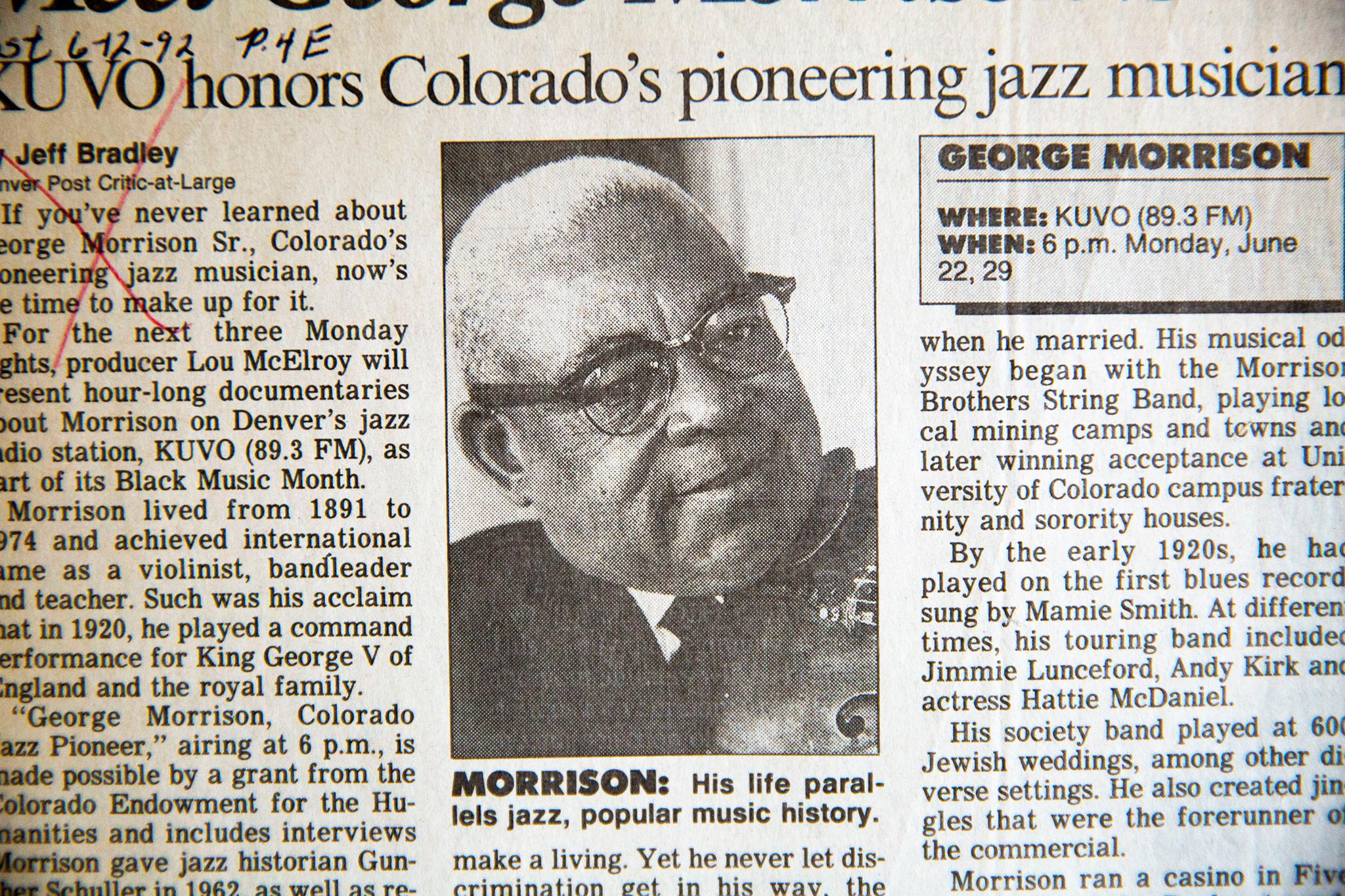

But, according to a 1992 Denver Post story, Morrison could not use his classical training to make a living: "Racism forced him to turn to popular music."

He returned to Denver from Chicago around 1918, two solid decades before Charlie Burrell won a spot in the Colorado Symphony (called the Denver Symphony back then). Since Morrison could not join a major music institution, he invested his time and energy in jazz.

"In those early days, we had three prominent white bands," he told Schuller. "Those were my competitors. But it wasn't long before my band grew so great in popularity that everyone wanted my band."

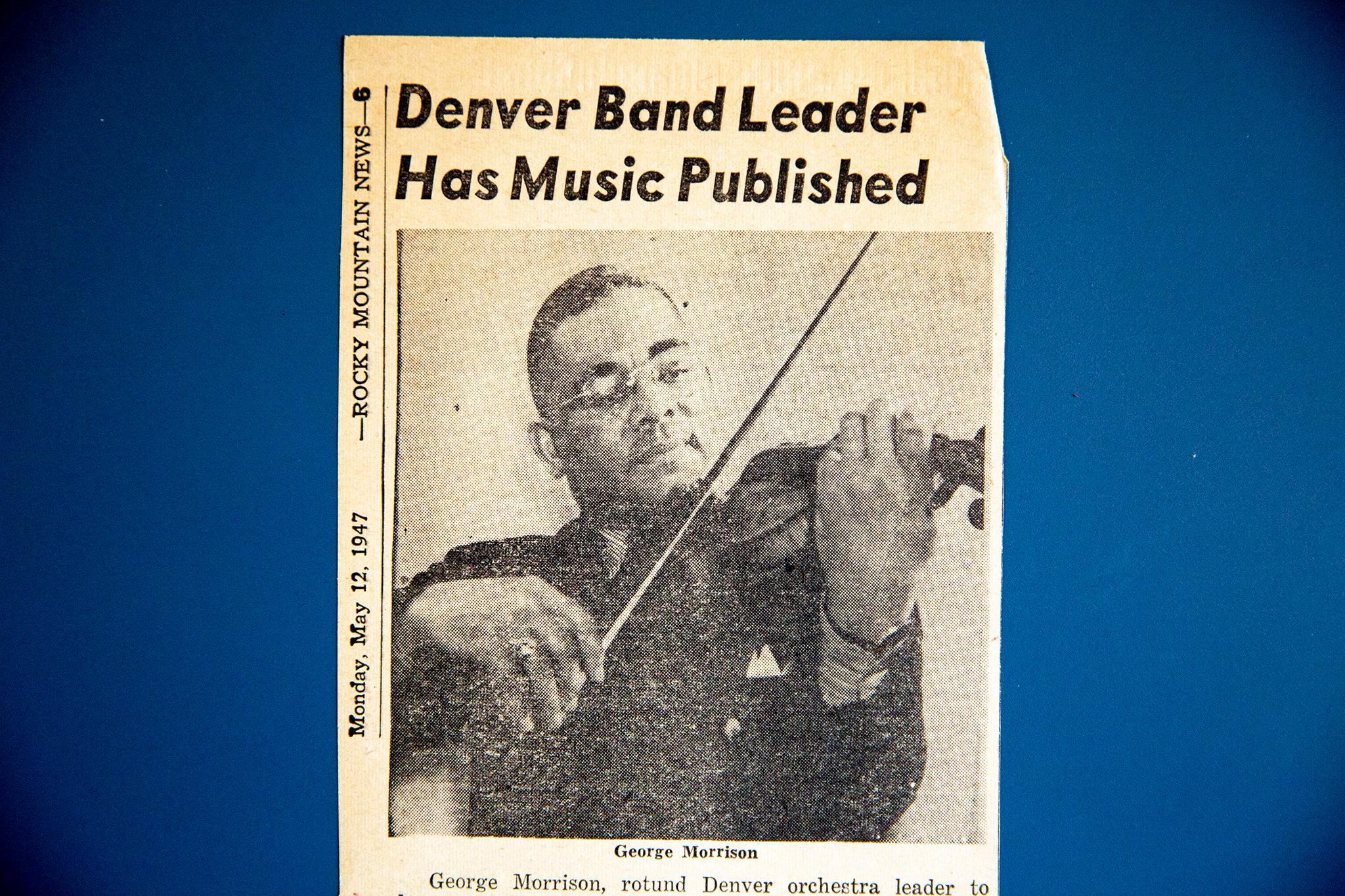

As his profile rose, Morrison and his band began to play Denver's Albany Hotel, which once stood at 17th and Stout Streets downtown. They'd play regular shows there for eleven years. A reporter for the Rocky Mountain News wrote about how that residency catapulted them to national fame.

"People from all over the city were clamoring for George Morrison," he told Schuller. "I built up such a reputation that people would pay me $50 just to make my appearance after booking another band there. Just so they could say George Morrison will appear here tonight."

As his name and music resonated in more ears, he and his band were invited to tour the country. He played New York and Kansas City, Salt Lake and Chicago. Hattie McDaniel, the East High School graduate who'd later win an Oscar for her performance in "Gone With The Wind," was among the musicians who traveled with him.

"Such was his acclaim," a Denver Post remembrance stated in 1992, "that in 1920, he played a command performance for King George V of England and the royal family."

Though audiences far and wide wanted to see him play, Morrison always stuck close to Denver.

He first moved to the city in 1911, after he married, and planted roots in the metro's growing jazz scene. Morrison would run a nightclub in Five Points, a major music hub in the west that earned the nickname "the Harlem of the west."

In the '20s, he operated another club in Golden, the Rockrest, that flourished until it was pushed out of town.

"We did a tremendous business under prohibition," he told Schuller. "I had a sign up there, 'This place is heated by George Morrison's music' - 'cause we never had a stove in it. We'd go all winter long. Between the moonshine and my music, we really kept the place hot."

But the speakeasy was dangerously close to Table Mountain, where the Ku Klux Klan often met to burn crosses and project their hateful credo across the Front Range. When the racist Klan threatened to bomb his business, he shut it down and hit the road again on tour. That wouldn't be his last run-in with the racist hate group.

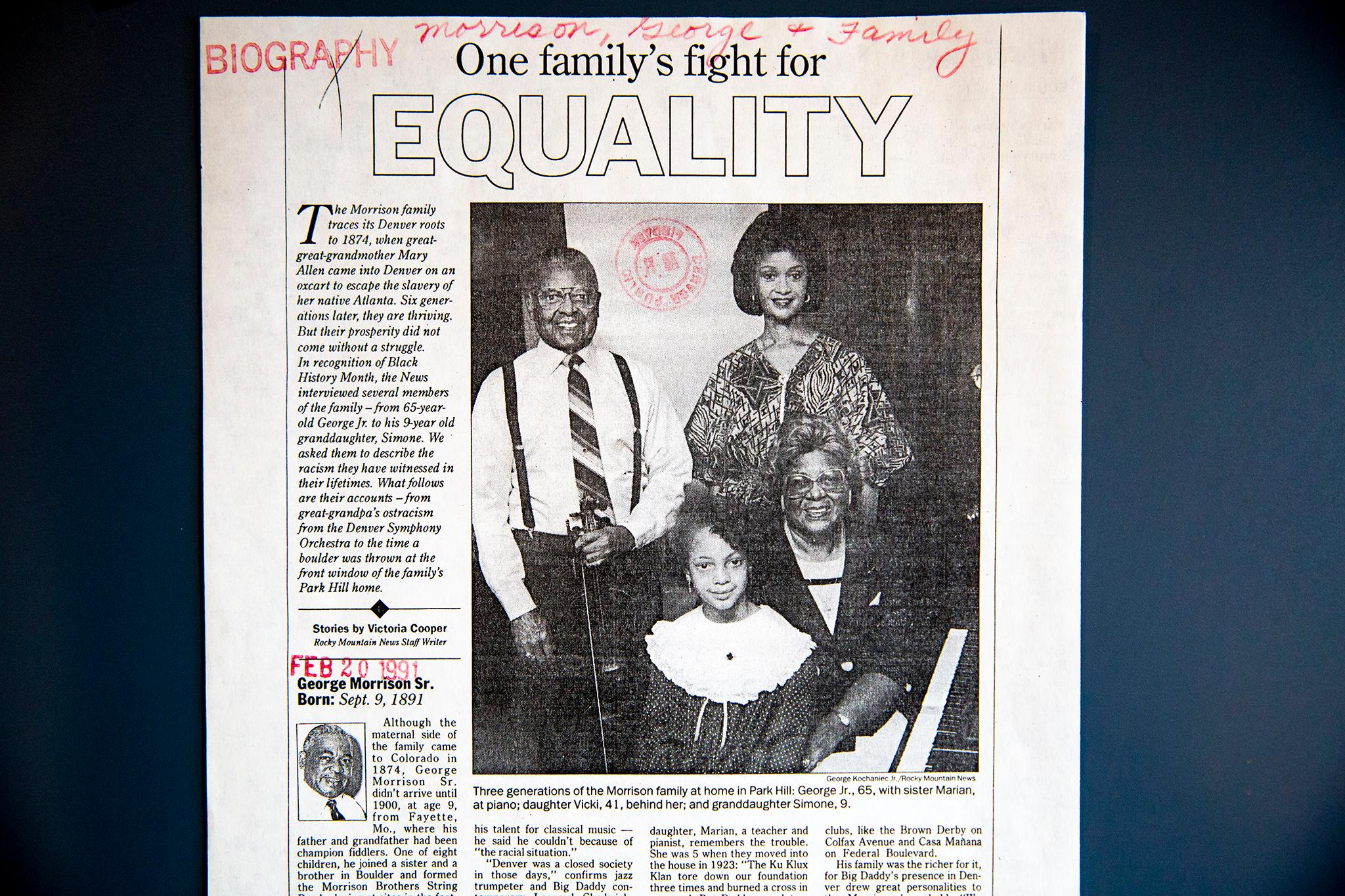

In 1921, Morrison began work on the home on Gilpin Street where he'd spend the rest of his life. The simple act of moving was itself a transgression, as he crossed a "red" line out of Five Points into a neighborhood previously off limits to Black residents. His family was one of the first in the city to do so, and the move was difficult.

"The Ku Klux Klan tore down our foundation three times and burned a cross in our yard," Morrison's daughter, Marian, told the Rocky Mountain News in 1991. "But daddy was determined to live where he wanted."

Morrison resisted more than hate to remain in Whittier. He also received numerous asks to leave town and join traveling bands as he grew older. Tempting as they were, he turned down every offer.

"When he had the opportunity to go with Duke Ellington and some of the other great jazz bands, he always said no," Marian told the Rocky. "He'd rather be a big fish in a small pond."

Instead, legends like Ellington would come to him, visiting at home on Gilpin Street.

Purnell Steen, Charlie Burrell's cousin, told us his lasting connection to Denver rendered him "the father of Five Points." His legacy echoed through the city and with the generations that flourished around him, as he transitioned from performer to music teacher. He'd instruct children at Whittier Elementary and Manual High School and was honored in 1973 when Denver Public Schools dedicated their sixth-grade music festival to him.

While he performed less often as he grew older, Gary and Joanne Goble said they've heard stories that Morrison and his family were known to bring out instruments on Christmas Eve and serenade their neighbors with carols. Like his childhood in Missouri, music was a way he connected with the people and community around him.

Morrison died in 1974. At his funeral, held at Shorter Community AME Church, Charles Burrell was one of six pallbearers who carried him to his final resting place.