As fentanyl dominates the city's drug supply, medical providers at Denver Health say they are changing the way they offer medication-assisted treatment for patients

Formally launched in 2019, the hospital provides an on-demand program that offered buprenorphine, a medication used to treat people with opioid addiction, to anyone interested in starting treatment. Their goal was to let people show up and get help whenever they're ready.

But according to Michelle Gaffaney, a physician assistant at Denver Health, fentanyl is so powerful that buprenorphine -- sold under the brand name Suboxone -- is no longer strong enough to help people wean off the drug.

"[The problem is] the way that fentanyl kind of acts in the system. It stays in the system for a longer period of time, it causes more severe withdrawal symptoms," Gaffaney said.

Fentanyl is so prevalent that people sometimes aren't aware it's in their system until a urinalysis is done, one local doctor pointed out. State lawmakers are currently debating a bill to increase penalties for the drug's possession.

At Denver Health, more and more people are now being prescribed methadone.

This is a much more potent medication used to treat people with opioid addiction.

Gaffaney said methadone is what's called a "full agonist," which means it more closely mimics the effects of opioids like heroin without the feeling of euphoria. Buprenorphine is only a partial agonist, and staff who use it have found it's harder to stabilize withdrawal symptoms or cravings. Gaffaney said buprenorphine can sometimes even worsen opioid withdrawal symptoms if it's started too soon after their last fentanyl dose, which isn't a risk with methadone.

But Methadone is only available for people 18 years and older, and Gaffaney said that's a problem, because the hospital has seen a spike in people 16 to 21 seeking addiction treatment for fentanyl use. Buprenorphine can be used by people as young as 16-years-old.

Tabitha Shackleton, a peer recovery coach at Denver Health, works closely with people experiencing homelessness through on-the-street outreach. She said fentanyl abuse is "rampant," but people tell her they won't go to the hospital if they know they're going to get Suboxone.

"They're like, 'No, I'm not doing it. It's not gonna be strong enough,'" Shackleton said.

Jason McBride, who works with young people to support violence prevention, said he's had to talk with teenagers about fentanyl.

McBride, who works at the Struggle of Love Foundation, said it adds another layer of things they need to talk about. He typically works with kids aged eight and up.

"These kids are out there taking lords knows what," McBride said. "Because there have been overdoses because there have been deaths, we have to talk more about it."

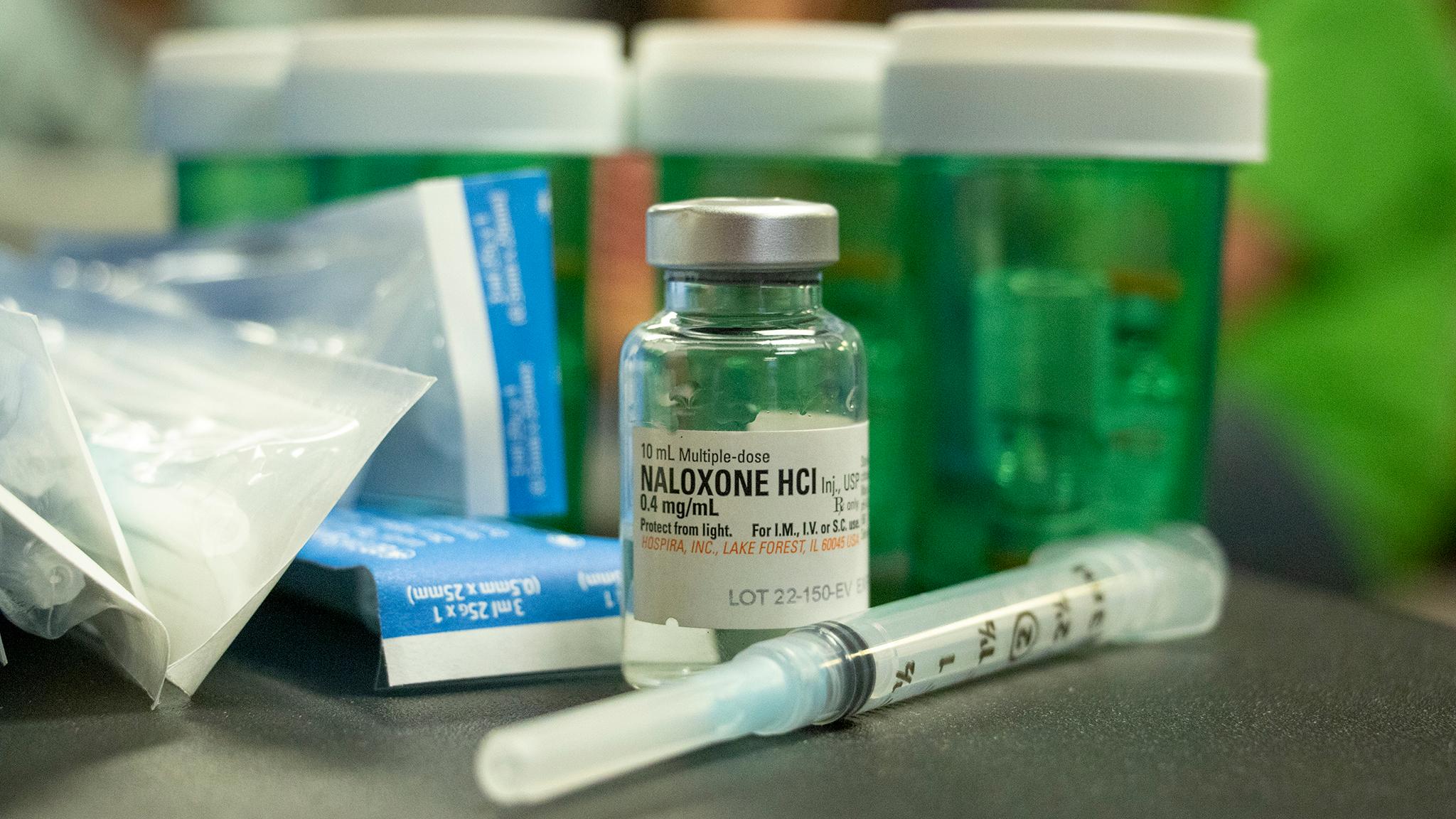

City peer navigator Shawna Darling runs the Wellness Winnie, a mobile health unit that provides stuff like naloxone and referrals to medical and other social services. Darling said she's noticed more people using drugs out in the open, and there are more people requesting naloxone and fentanyl-testing strips. The Wellness Winnie works closely with organizations like Struggle of Love.

While she can make some referrals, she said long-term treatment options remain scarce.

"There's just not a lot of options," Darling said. "It's really sad."

Fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that can be anywhere between 50 to 100 times stronger than heroin or morphine, has completely infiltrated the city's drug supply.

The issue is not new in Denver. Fatal drug overdoses offer a more grim reference point: City data on drug deaths showed fatal overdoses involving the synthetic opioid tripled from 2018 to 2019.

The public was warned about fentanyl's growing presence in November 2019, when Denver police joined the city's health department in announcing that the drug had been found in "brick-like form" for the first time in the city.

In 2018, 17 people died from overdoses involving fentanyl in Denver. Last year, preliminary numbers show 235 people died from drug overdoses involving fentanyl -- nearly half of the city's 472 drug-related deaths. The city has already had 12 drug deaths involving the synthetic opioid in 2022 as of March 31, according to the Office of the Medical Examiner.

People who overdose on fentanyl require multiple doses of naloxone, and Gaffaney said this has led the hospital to give people multiple boxes. There are some people being brought to the ER who are put on naloxone drip to reverse a fentanyl overdose.

"I'm telling patients, use one, call 9-1-1, stay with person," Gaffaney said. "If they don't respond in five minutes, use another one."

The city shipped out 1,000 orders of naloxone and fentanyl strips last week, according to city public health spokesperson Courtney Meihls.