Cities across the nation have dealt with upticks in gun violence since COVID-19 arrived, and police and communities are pushing for ways to deal with the bloodshed.

Violence can happen anywhere, but Denver Parks and Recreation is using its unilateral power to prevent it in the city's green spaces by simply closing parks to the public.

On Thursday, the department announced it would close La Alma-Lincoln Park indefinitely after 63-year-old Gary Arellano was shot there Wednesday night.

Arellano was a longtime regular there, his niece, Jami Arellano said. He was known by neighbors and park staffers as someone who deeply loved his community and the grassy area at its heart. On Wednesday, he tried to break up a fight between two young women when he was shot multiple times. Denver Police arrested a 24-year-old for the crime.

"He just didn't deserve to go out like that," Jami told us as she and her uncle's friends gathered at a picnic table where he'd often sit. "He was here in his neighborhood where he did feel safe, and tried to be the peacemaker so fights weren't going on, so kids could go to the rec center, to keep it open. This was his neighborhood and he was trying to protect it."

Jami and Tracey Arellano, Gary's sister-in-law, both said they were unsettled to see fencing bisect the grass, which surrounds the rec center but leaves a playground open for use.

"Gary wouldn't want this park to shut down because of him," Tracey said, gazing at the metal barriers.

Cyndi Karvaski, a spokesperson for the city, said Parks and Rec has a duty to protect staff and residents on its property. If the city as a whole experiences a rise in violent crime, and if it begins to creep into parks, her department will shut them down to keep people from dying in places where they hold responsibility.

"We have the authority to close parks as necessary for sanitary, health and safety measures," Karvaski told us. "That would be our response to the violence that is occurring."

This is the third time this year the department has cordoned off parts of La Alma-Lincoln Park due to issues with violence. It only reopened a few weeks ago. On Tuesday, a day before Arellano was killed, Karvaski said the Denver Parks and Rec softball team was playing on the sports field there when the game was interrupted by gunfire.

Violent crime is still higher in Denver than it was pre-pandemic. Numbers of arrests, generally, have been pretty consistent and data do not suggest park closures have had an impact.

It's still early going in 2022, but the average number of violent crimes reported by Denver Police each month have continued to hover above pre-pandemic levels.

This year, so far, Denver saw an average of 303 violent crimes per month between January and March. (This includes murders, assaults and sexual assaults, and we're not including April since the month isn't over yet). Last year, that number was 333 violent crimes per month, the highest since DPD's open records begin in 2017. It was 310 in 2020.

In 2017, 2018 and 2019, that monthly average hung below 290. Violence recorded by DPD hasn't risen in a massive way, but there has been a difference since the pandemic began.

Property crimes, on the other hand, have grown substantially since 2020. On average each month, DPD logged 50% more thefts of all kinds in 2021 than it did in 2019. So far this year, that figure is slightly higher.

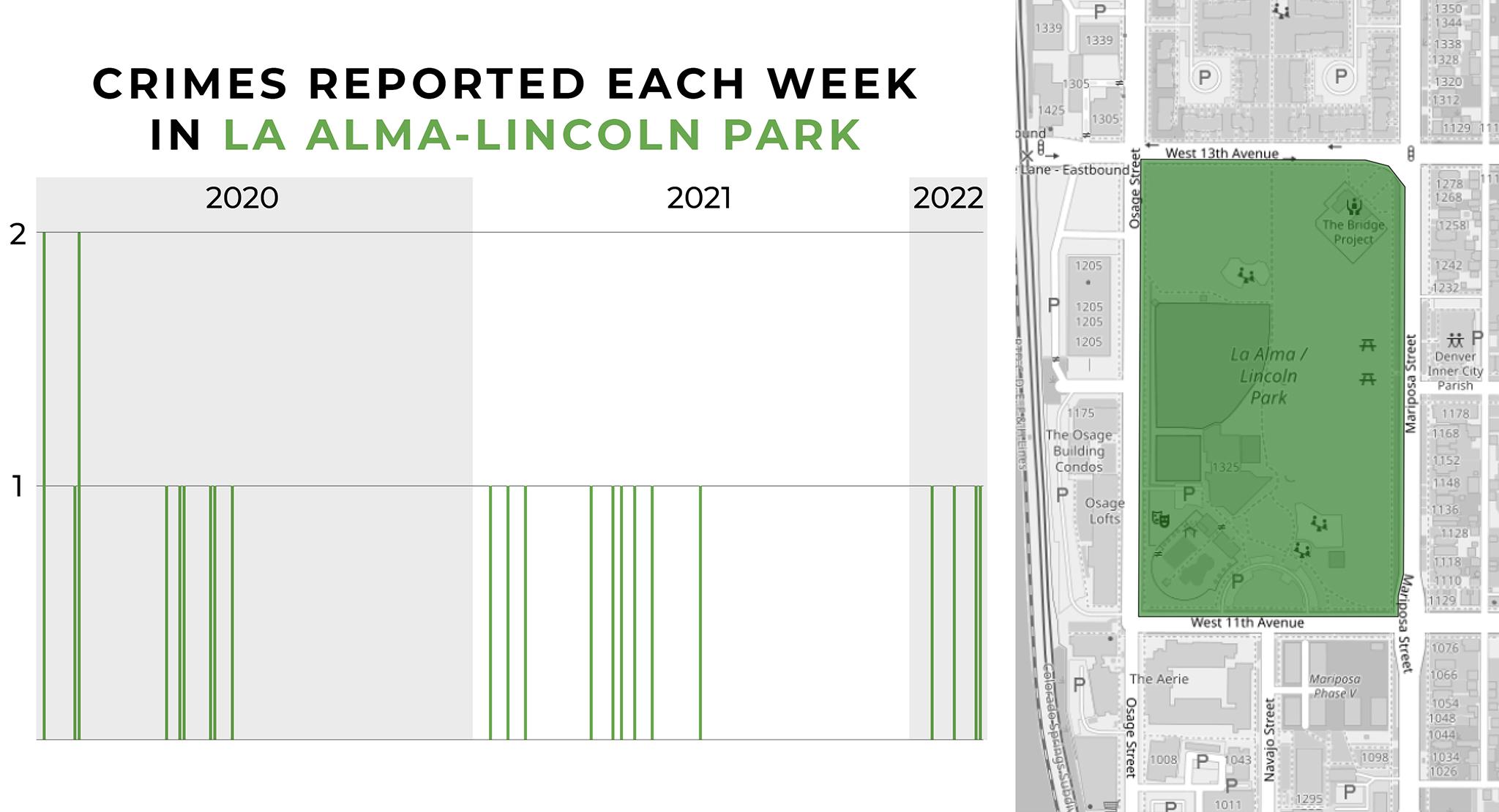

La Alma-Lincoln Park has generally not been a place for arrests and citations. Our analysis of Denver crime data for the confines of the park show there hasn't been more than one crime per week recorded there since September 2020, and the weekly count hasn't risen above three since January 2017. Most weeks, no crimes or citations were recorded there.

City Council member Jamie Torres, who presides over the neighborhood, told us she hasn't heard the park itself is any more or less safe than the rest of the neighborhood.

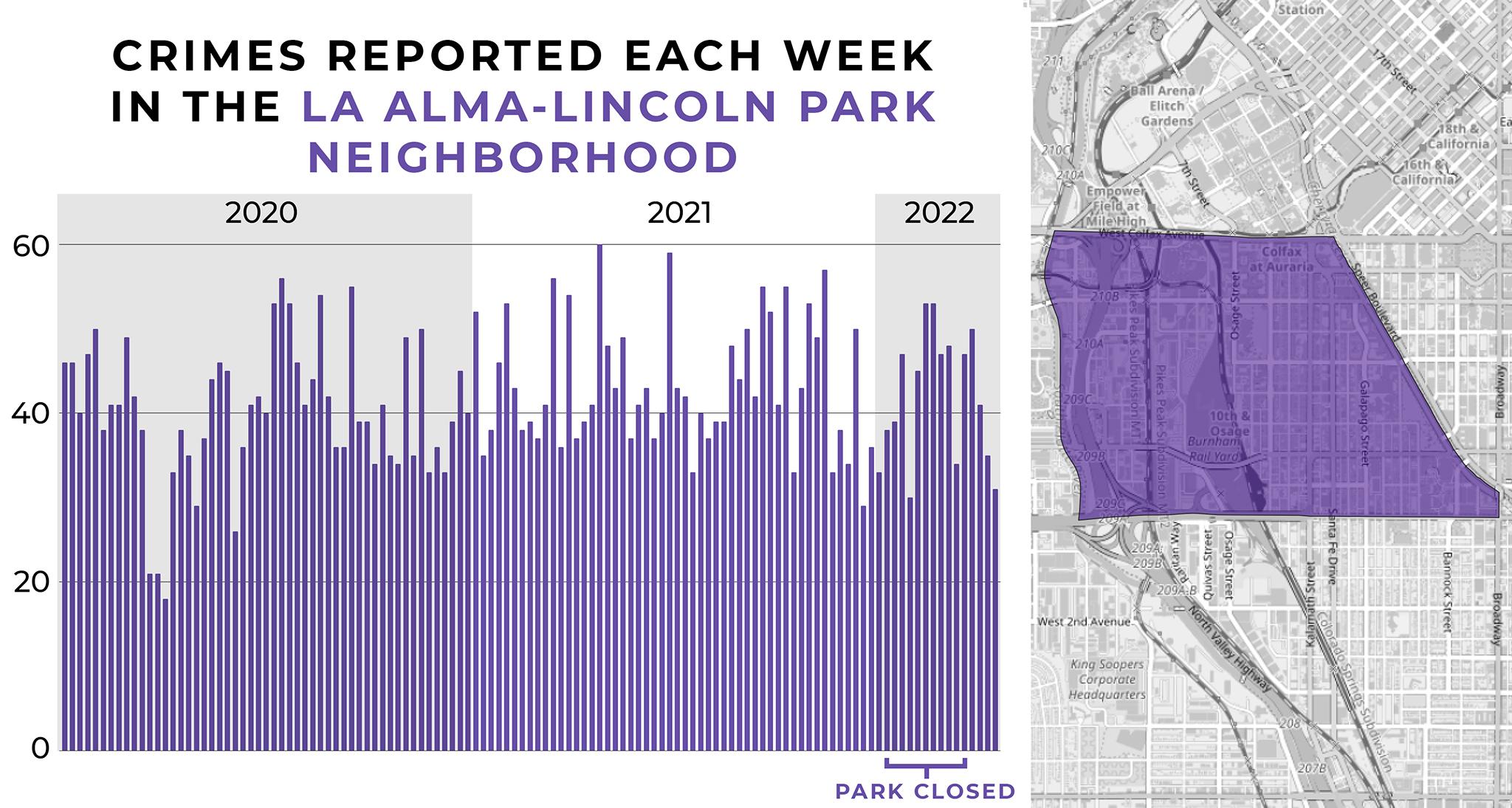

Denver Parks and Rec closed La Alma-Lincoln Park for three weeks in December and again between Jan. 14 and Mar. 24. The total number of crimes reported in the greater La Alma-Lincoln Park neighborhood did hit some of their lowest weekly levels during the second closure, but the general weekly count remained consistent in the neighborhood.

DPD did not respond to a request for comment on whether park closures have impacted the city's general crime levels, violent or not.

Park closures may be necessary in the short term, but residents and community leaders don't want to see people locked out of grassy spaces indefinitely.

Karvaski told us there is currently no set date for fences to come down at La Alma-Lincoln Park, and that Parks and Rec is still figuring out what the criteria may be to reopen it.

"We're just going to have to see how things go," she said.

Council member Torres told us she's generally OK with the park's closure in the short term. She heard from Parks and Rec that many of the rec center employees knew Arellano and needed time to grieve, and she said she gets the space could use some time for a cool-down. But she's hoping the tragedy that unfolded there this week won't keep people locked out of the place for too long.

"I do want to see the park and the rec center reopen," she said. "I want to make sure they're waiting for something concrete to happen, otherwise they're just closing for closing's sake."

In the meantime, Torres said DPD has increased patrols in the area surrounding the park, a move she hopes will stick for the long-term. She's also lobbying the city to install HALO surveillance cameras there, which she thinks would help keep an eye on things and prevent more violence from unfolding.

"I don't believe in putting HALO cameras everywhere," Torres told us, but La Alma-Lincoln Park "is definitely a public city asset that should have eyes on it."

Denver's city attorney is also pushing for legislation that would outlaw concealed weapons in parks - open carry is already illegal.

City-wide, DPD has been increasing patrols and working with community members in a growing number of crime "hotspots" that they hope will keep violence from spilling into neighborhoods this summer. Criminal justice reform advocates are skeptical of their approach and feel the root causes of violence need deep, system-wide remedies.

"With insecurity and anxiety with things such as the pandemic or job loss, things of this nature, there's going to be a rise in crime, and violent crime in particular," Robert Davis, head of the resident-led Reimagining Public Safety task force, told us. "If we don't address those major socioeconomic issues and stop tying to put a Band-Aid on an open gash, then we're going to continue to have the same problems."

While he didn't want to comment on La Alma-Lincoln Park's closure, specifically, he did say he could see why a short-term shutdown would be appropriate. But he said a long-term closure might be emblematic of a nationwide failure to really understand violence in this country.

"This is the biggest challenge. All across the nation, we all look at symptoms without looking at the underlying cause," he said. "We need to become courageous enough to look at the real issues."

This is something Tracey Arellano, Gary's sister-in-law, talked to us about in the park.

"We need more community outreach. They don't need to shut things down. These kids need help, bottom line," she said. "They close this park down, where's everybody going to go? To the next park. And the same stuff is going to happen."

Jami Arellano, Gary's niece, said she intimately feels the complexity surrounding violence prevention and the new fences at the park. The mother of an 18-year-old, she worries about her son every time he steps out their front door. On one hand, she'd like to see a more visible police presence at the park. On the other, she worries what could happen to kids like her son who end up on the wrong end of an interaction with a cop.

"You're damned if you do, you're damned if you don't," she said, shaking her head.

Still, she told us the barricades at her uncle's favorite spot feel like an insult to his memory.

On Thursday night, after city workers installed the new fencing, she and her family held a vigil in the grass. They lit candles and released balloons, many of which became tangled in a tree towering over them.

"The balloons didn't want to leave," she said, gazing up at those that remained. Her uncle Gary may not be here to see what happens next, but a part of him will always be here.