Climate change is making Denver hotter, which means air conditioning is becoming more of a necessity than a nice thing to have. But AC units need power, and we wondered if their proliferation might actually feed back into the city's climate emissions, creating a hot, unfortunate feedback loop.

The short answer: AC probably isn't our biggest issue when it comes to sustainability, but it does play into growing energy demands as we move away from gas and go all electric.

Here's what we know about residential energy use in Denver:

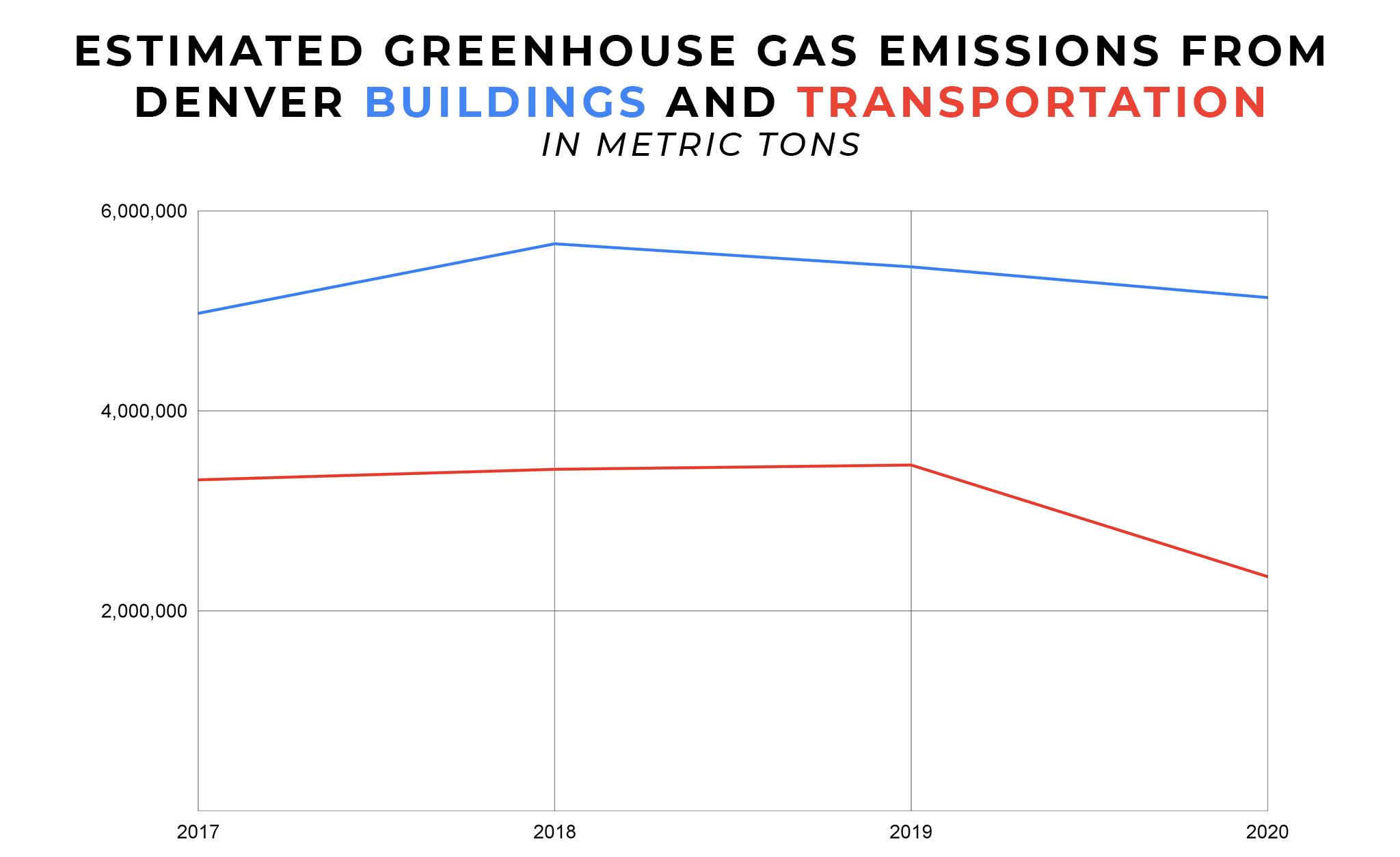

According to data compiled by the city, Denver's buildings account for the largest category of our carbon dioxide emissions. This is CO2 associated with the electricity we use when we plug things in and gas we burn when we run stoves and furnaces. They estimate buildings accounted for 5.3 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions on average between 2017 and 2020. For context, that's about half of their estimate for Denver's total greenhouse gas load in 2020.

Average estimates for transportation are around 3.1 million metric tons in that timeframe. While the transportation figures fell significantly during COVID, levels associated with buildings did not.

In 2020, residential buildings (homes and multi-units) accounted for about 40 percent of all emissions tied to buildings, mostly through gas and electrical use. It was 20 percent of our total output.

Simply put: We use a lot of energy where we live, and our appliances make up a decent segment of Denver's overall climate impact.

More AC means more energy use, which means Xcel Energy has a heavier load to balance.

Kelly Flenniken, a spokesperson with the utility, said Xcel doesn't track individual appliances like air conditioning, but they do have estimates on overall appliance use in the city. While new dishwashers, cooling units and laundry machines are more efficient than their older cousins, Flenniken said sheer population growth has offset efficiency gains.

"There's just more people. More people and more appliances," she told us. "We have absolutely seen an increase in electric demand."

(Local highway projects have a similar problem: Cars are getting more efficient, but wider highways mean more traffic and more pollution.)

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

A spokesperson for the city's climate office told us about 70 percent of Denverites have some kind of AC in their houses, so there is room to grow as things get hotter here.

And there's another thing pushing Denver to consume more electricity: climate change measures that are meant to get us off fossil fuels. This year, the city offered rebates to help people pay for heat pumps that keep houses warm with electric energy rather than natural gas. There are also pushes to get people to stop using gas lawnmowers and switch to electric cars - all of these things move us away from gasoline and add more demand to Xcel's electric infrastructure.

So the question is: Can Xcel sustainably handle all that demand?

The utility has pledged to go 100% renewable by 2050, which means things like air conditioning units and heat pumps will contribute to Denver's climate impacts far less than they do today. In 2021, more than half of Xcel's power supply to Denver was still generated by coal (31 percent) and natural gas (28 percent).

Michael Deru, a researcher with the National Renewable Energy Lab (which is based in Colorado), said Xcel should be able to handle increasing electricity needs, but it will get tricky at certain times when everyone tries to use their appliances at once.

"They're planning for this, they have projections for the growth and the load," he said. Still, he added: "Being able to ensure a resilient and durable and reliable electric grid is gong to be really challenging."

If super-hot summers are our future, so is citywide AC use for longer periods of time.

Xcel has already expressed concerns that they could have trouble responding to a massive heatwave next year. This summer, utilities in the Midwest have said surging electricity demand could result in rolling blackouts.

Flenniken told us Xcel has a list of big, power-thirsty customers who have signed up to cut their service in the event of an emergency, which would help avoid residential power losses. Still, she said average consumers will see some impacts if if their systems are pushed to the limit.

"What we would do in that worst case scenario is call on all of those pieces, call on those interruptible customers, call on our other community utility providers and then talk to our customers about how they can conserve their energy usage," she said. "Really extreme heat and really extreme cold, or other types of weather events, are really becoming more and more common, so we really do plan for that."

And even if heatwaves or snowstorms don't push Xcel to rolling blackouts, it could still impact how much you spend on your utility bill. Right now, regulators are working through rate hikes to deal with demand spikes in Colorado during a 2021 snowstorm.

NREL did a study of Los Angeles that found the city could be powered by 100 percent renewable energy in a way that is sustainable, equitable and wouldn't break the bank. Deru said Denver could also reach a future like that, but it will take intentional work from Xcel to ensure we have enough renewable power and intentional work from the city to help people move to electric appliances that are efficient and won't blow past Xcel's capacity.