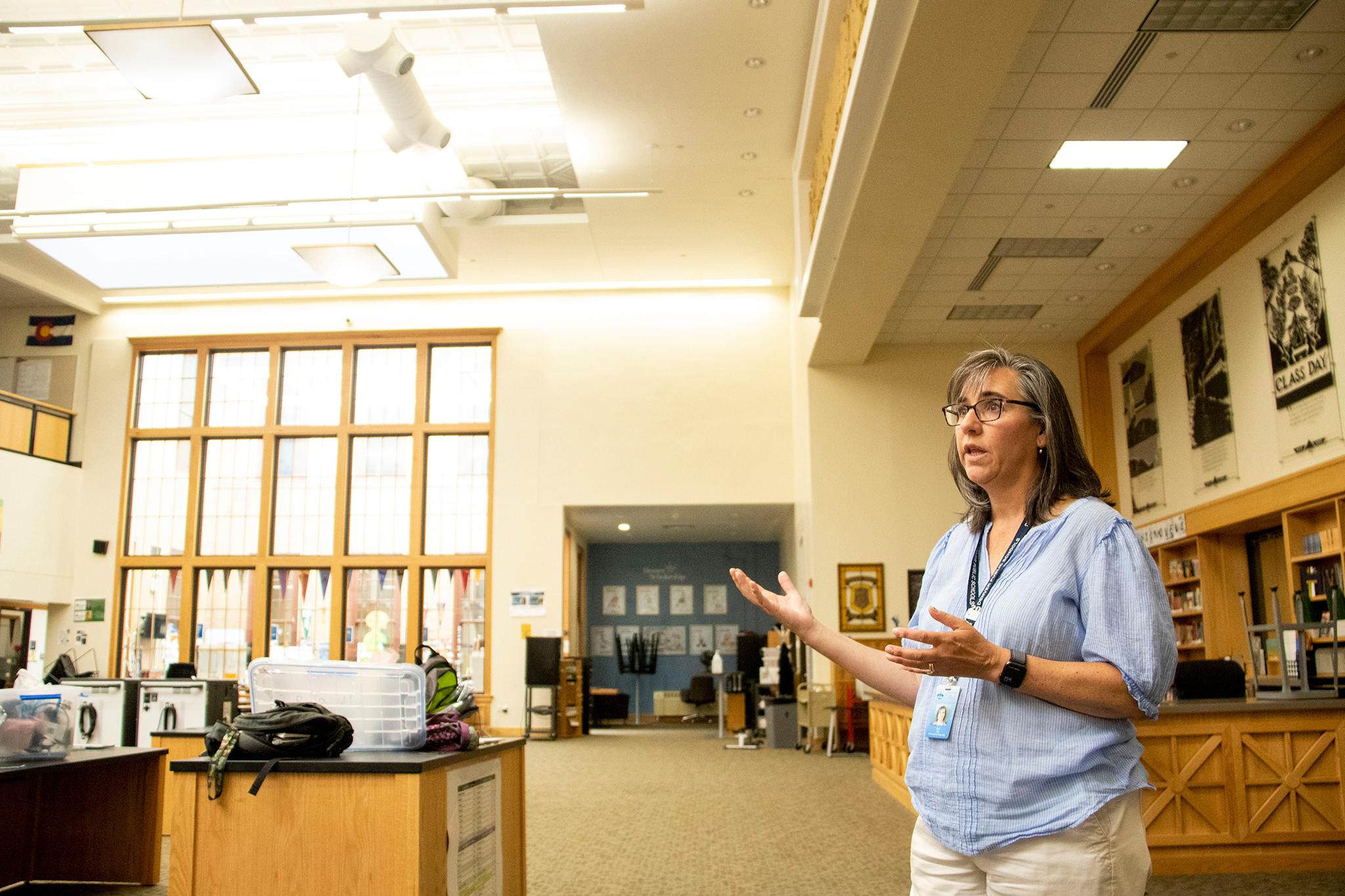

Joni Rix has managed Denver Public Schools' environmental quality program for about 20 years. In all her time at the district, she's never seen so much money go towards helping kids breathe easier in class.

In 2020, the federal government set aside $54 billion in an "Education Stabilization Fund," one in a slew of stimulus programs meant to help the nation bounce back from the pandemic. Part of that money was meant to help schools improve ventilation in their buildings, a key strategy in helping kids return to class while an airborne virus infected people.

DPS received $300 million from the program and has earmarked $25 million for indoor air quality projects. That will go toward hardware, like improvements to air systems. It's also paying for 800 sensors that are currently going into classrooms and libraries around town.

Rix said her job has changed in this post-pandemic world.

"One of the silver linings, I guess you could call it, from COVID is that it definitely has focused more of an attention on indoor air quality," she said. "It's always been important, but it's definitely risen more to the top. It's given us that ability to get support from people that probably never gave it much attention, so that we could do something like this."

Initially, she pitched the district on a handful of monitors that would float around schools over the next five years. Instead, the administration told her to go big. The sensors will remain in schools permanently, and feed real-time data to a central system that Rix and her team can monitor each day.

While the new tech will help the district keep air flowing and COVID transmission at bay, Rix said monitoring is becoming increasingly important as climate-change-fueled wildfires also dump smoke onto the city.

The sensors track:

- CO2 levels, which indicate stagnant air that could contain airborne viruses.

- Particulate matter, air pollution that comes with wildfire smoke and also can concentrate during winter inversion events.

- Volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, which comes from car exhaust and aerosol products and can be converted into ozone.

- Humidity and temperature.

There are no official health standards for indoor air pollution, Rix said, so it's not likely that kids would be pulled out of class based on this new data.

There are recommendations for indoor air pollution that she said would be communicated to schools. If CO2 levels are high, for instance, they might ask teachers to open doors or windows for better airflow. But Rix said she sees the new monitoring program as a part of longer-term progress that forces action.

The district has tried to understand its air before. Love My Air, a partnership between DPS and Denver's health department, installed similar monitors outside school buildings to help make decisions about when it's OK for kids to play outside. Rix said the new indoor sensors should also help with legacy health problems.

"With this, the hope is maybe we can decrease asthma incidences, too, because DPS has a higher incidence of asthma than the nation," she said. Still, school is only one place where kids may be exposed to pollution: "It's hard. There (are) always so many other contributing factors."

Jeronimo Palacios, a University of Colorado Boulder environmental engineering student, met Rix at North High School Tuesday to help install the monitors. He said researchers and officials are worried about how exposure to pollution can impact learning, too. More and more studies have found that exposure to bad air, particularly particulate pollution, can impact both behavioral and cognitive functions in children.

"It's interesting to see how these things all come together to impact your education," Palacios said, "so it's important that we collect as much data as possible from all different regions to determine which schools may need better ventilation for both teachers and students to better develop and perform."

With this new gear, DPS joins a list of school districts across the country pursuing more (and better) data.

Serene Almomen is the CEO and co-founder of Senseware, which makes the monitors that DPS bought with the federal grant money. The company started as an internet-of-things developer but found a niche at the nexus of breathing and education.

She told us Denver's schools are far from the first in the nation to implement this tech. Her company has outfitted classrooms in Washington, D.C., Atlanta, Tulsa and Chicago. Districts in California, North Carolina and Missouri are also pursuing similar measures.

Almomen said administrators are focused on indoor air, but they need information before they can actually do anything.

"The threats are invisible and the solutions are invisible," she said. "Some schools thought, "We need to know before we act.'"

Rix with DPS said the monitors themselves are wallflowers but she's looking forward to learning more so she can find some of those invisible solutions for the kids she serves.

"(The sensors) are pretty nondescript, nothing exciting about them," Rix said. And yet: "I'm excited."