Denver is poised to install speed bumps for the first time outside of city parks.

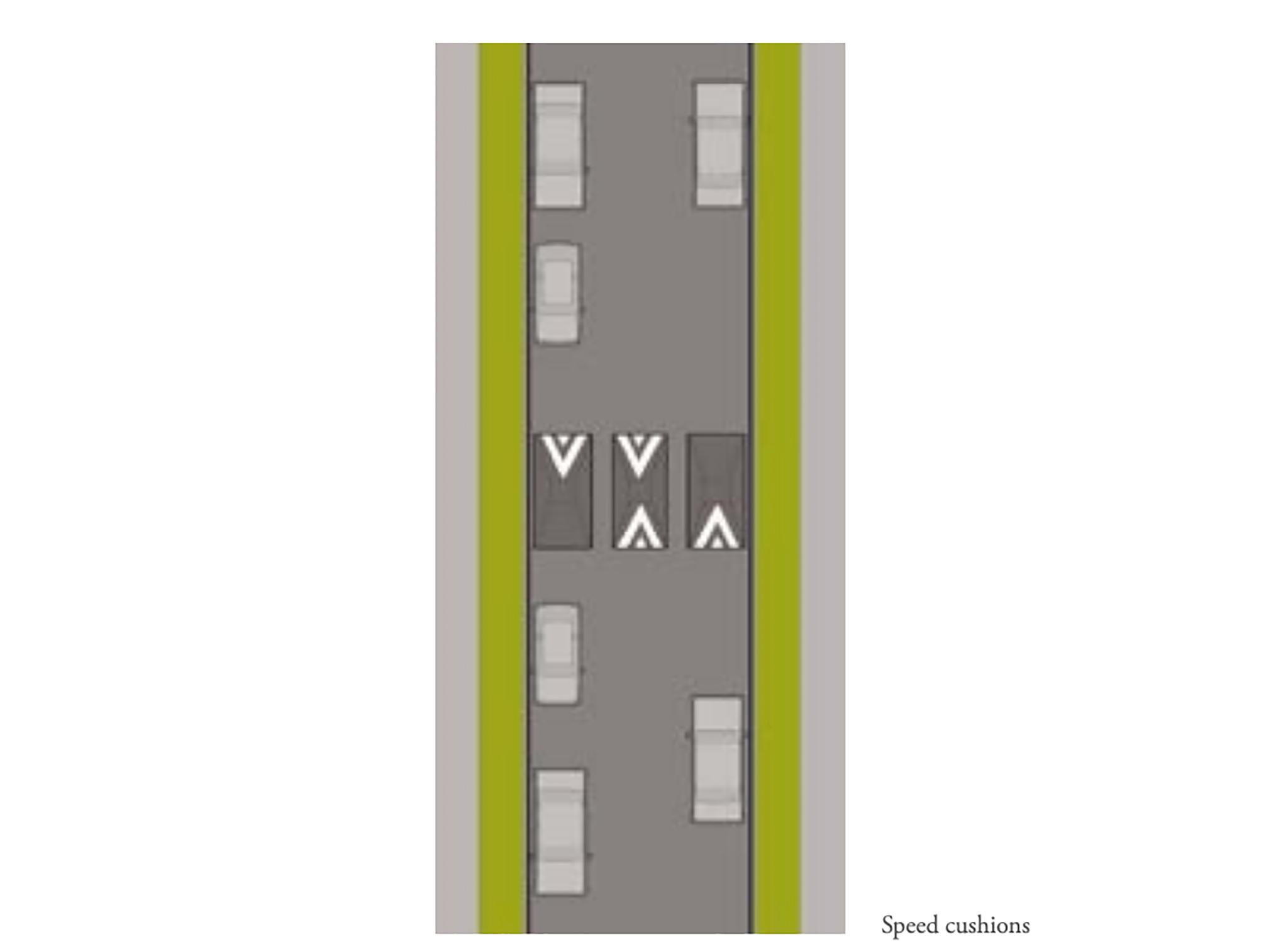

Well, they're actually not "bumps," they're speed "cushions." The distinction is more than semantics, the vertical traffic-slowing tech that Denver's Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (DOTI) wants to use is different than the speed "tables" you might have seen in places like Cheesman Park. Cushions are smaller and segmented, which allows emergency vehicles to drive past them smoothly. Regular car axles aren't wide enough to straddle them so, ostensibly, drivers will have to slow down if they encounter them.

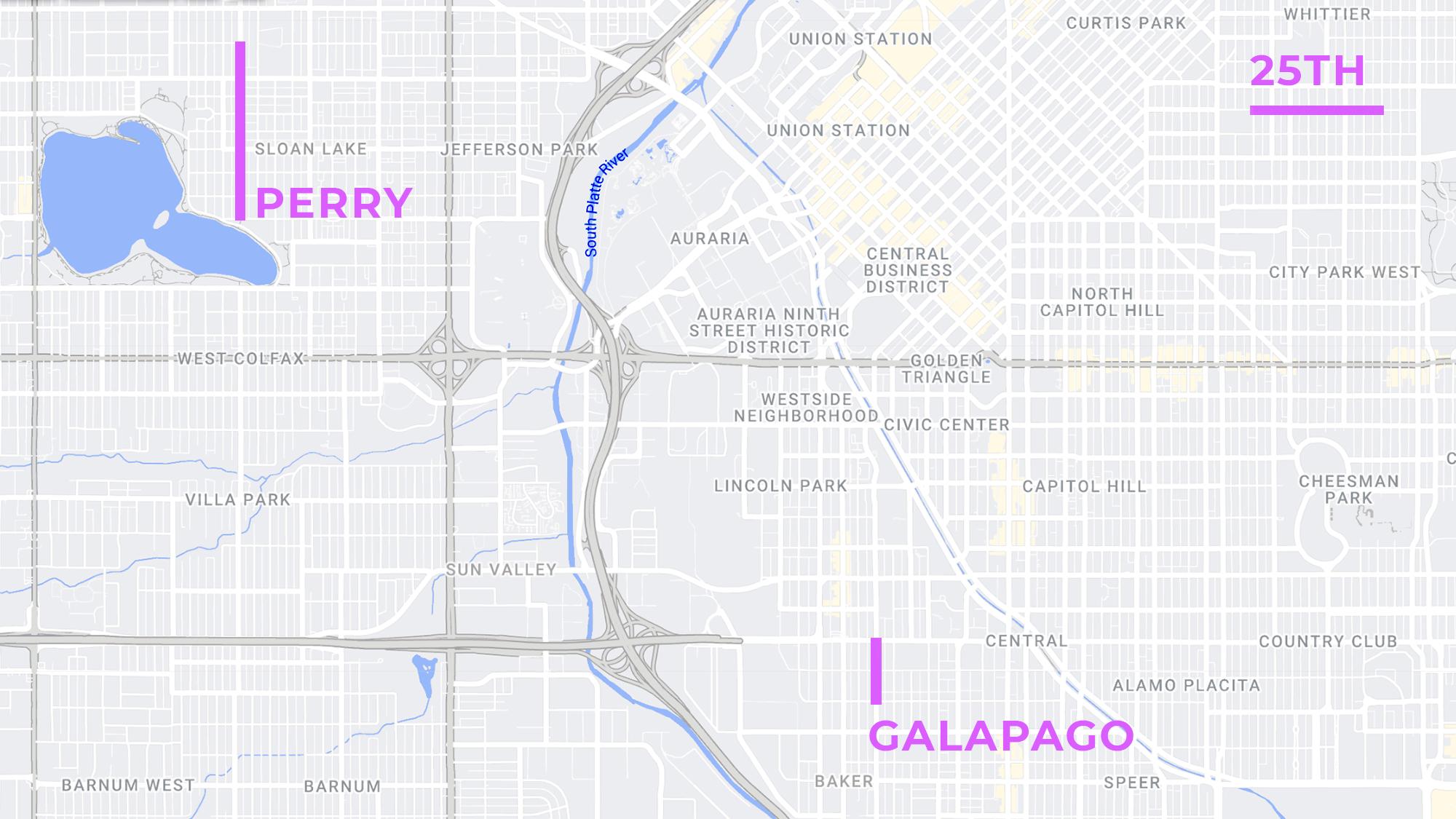

These new obstacles aren't necessarily permanent. They're part of a pilot project to increase safety for cyclists on three designated neighborhood bikeways:

- Galapago Street from 4th to 6th Avenues

- Perry Street from 20th to 27th Avenues

- 25th Avenue from Lafayette to Vine Streets

If the pilot works out, Denver may start installing them in more places.

Why hasn't Denver done this yet?

The city has committed to curbing deaths on roadways for years, but they haven't exactly been successful in that effort. 2021 represented a record-high for traffic fatalities in 20 years, and there's no indication things have slowed this year. It's likely the sound of speeding cars is a regular thing in your neighborhood.

Denver officials are trying a bunch of things to deal with the issue. They're investing in the scariest roads, like Colfax Avenue and Federal Boulevard, to reconfigure them towards transit and pedestrians.

Last December, City Council also voted to lower speed limits on neighborhood streets to 20 miles per hour. Still, as DOTI lead transportation engineer Emily Gloeckner puts it, this won't work if people don't obey the rules.

"In a perfect world, obviously, we'd want everyone to be courteous to each other and behave, but we know that's not necessarily the world that we live in," Gloeckner said.

Generally, Gloeckner said speed bumps - cushions, tables - could be part of a multifaceted solution to deal with overzealous drivers. In the past, officials worried that true bumps, not the segmented cushions, might impede emergency vehicles or snow plows. She said there's also a lot of study that shows drivers tend to speed up in between bumps and cushions, so there's a worry the city might spend a ton of money on infrastructure that won't really make a difference. Beyond that, neighborhoods can get noisy with these kinds of obstacles as cars and trucks lurch over them.

There's another element to this: speed bumps don't quite work unless you go all-in. If the city installs them on one street, Gloeckner said, drivers will probably just go speed on others. It's why they could be a perfectly good solution for the neighborhood bikeways, since officials like her want to discourage too many cars from riding alongside cyclists.

She said her department is being "so cautious" about this because they know other cities have implemented similar measures and then had to remove them later. It's cash they don't want to burn.

Instead, they've been using street markings and posts to make roadways appear thinner, a cheaper Jedi mind trick that slows drivers and narrows spaces that pedestrians have to cross.

Other nearby cities do have speed bumps, and things are generally OK. Denver's street safety advocates hope DOTI's trial works so they'll install more.

Jill Locantore, executive director of the Denver Streets Partnership, said mobility activists like her have been waiting for these cushions for a long time.

"It's ridiculous that the city has taken so long to implement this very basic measure. We're not talking about newfangled tech," she said.

Denver's surrounding suburbs have speed bumps, she told us, "and as far as a I know, it snows in those cities and they have emergency vehicles."

We called up Kyle Kammermeier, an engineer with Lakewood's Transportation Engineering Department, who confirmed they do have traditional speed "humps" - a three-inch rise over 12 feet - and that city services get along fine with them. He said the West Metro Fire Protection District has OK'd their use pretty much anywhere in town. He also said their plows can handle scraping up against them, but added their drivers know where they are and deal with them accordingly.

Yes, he said, drivers speed up in between them. Yes, they can be noisy. He, Gloeckner and Locantore all said there's no "silver bullet" to dealing with bad-faith driving. Kammermeier said he's heard complaints from drivers who don't love slowing down.

"It can add time to your trip, but the benefit that can gave to the residents of a neighborhood it outweighs that," he said. "Or it can. It's subjective, of course."

Kit Lammers, community services director for Edgewater public works, said his town has avoided speed bumps for the same reasons Denver has, though they are happy with two "raised crosswalks" they've installed near a school.

For her part, Locantore said she's hoping the speed cushions' pilot period doesn't last too long. They, along with all the other measures Denver is pursuing, are needed now.

"The city likes to study things to death, and I don't think this needs to be studied this much. There is a citywide appetite for slower speeds on our streets," she said. "We should just be building traffic calming everywhere."

So, what if you want a speed bump in front of your house?

It's not that simple. Gloeckner said residents should call 311 or use PocketGov to let them know if there are places where speeding is a problem. Her department will look into the issue, maybe even hire a contractor to set up gear to study traffic in that area, then decide if your area of complaint is a problem and see where it stacks up compared to all of their other priorities.

"It takes money to do anything," she told us.

If they find a lot of cars are pushing more than ten miles-per-hour over the speed limit, she said, that might be a sign it's time to do something.

While the solution will probably not be a bump or a cushion, at least for now, Gloeckner did say she regularly green-lights improvements that comes from complaints: "On average, I sign 35 work orders a month to make a change based on a 311 call."

Finally, a fun fact:

You may be saying to yourself: My neighborhood doesn't have speed bumps - cushions, whatever - but we do have these dips that slow drivers down.

Yep, you better hit the brakes before you encounter one of these "cross pans," lest you scrape your ride on asphalt. But DOTI spokesperson Nancy Kuhn told us they're not primarily to control speed. The little divots are mostly about funneling stormwater across roads, though they do have that secondary, unintended benefit. Fun, right?