It's just a few days before students return to Lowry Elementary, and Ellen Petrila is sorting through wreckage of last year.

"At the end of last spring, it was kind of just a mad dash to just put stuff away so we could be done which, in the spring, seemed like a really good idea," she laughs, "until I came back this fall and I opened all our cabinets and stuff and I'm like, this is a nightmare. I cannot start the year like this."

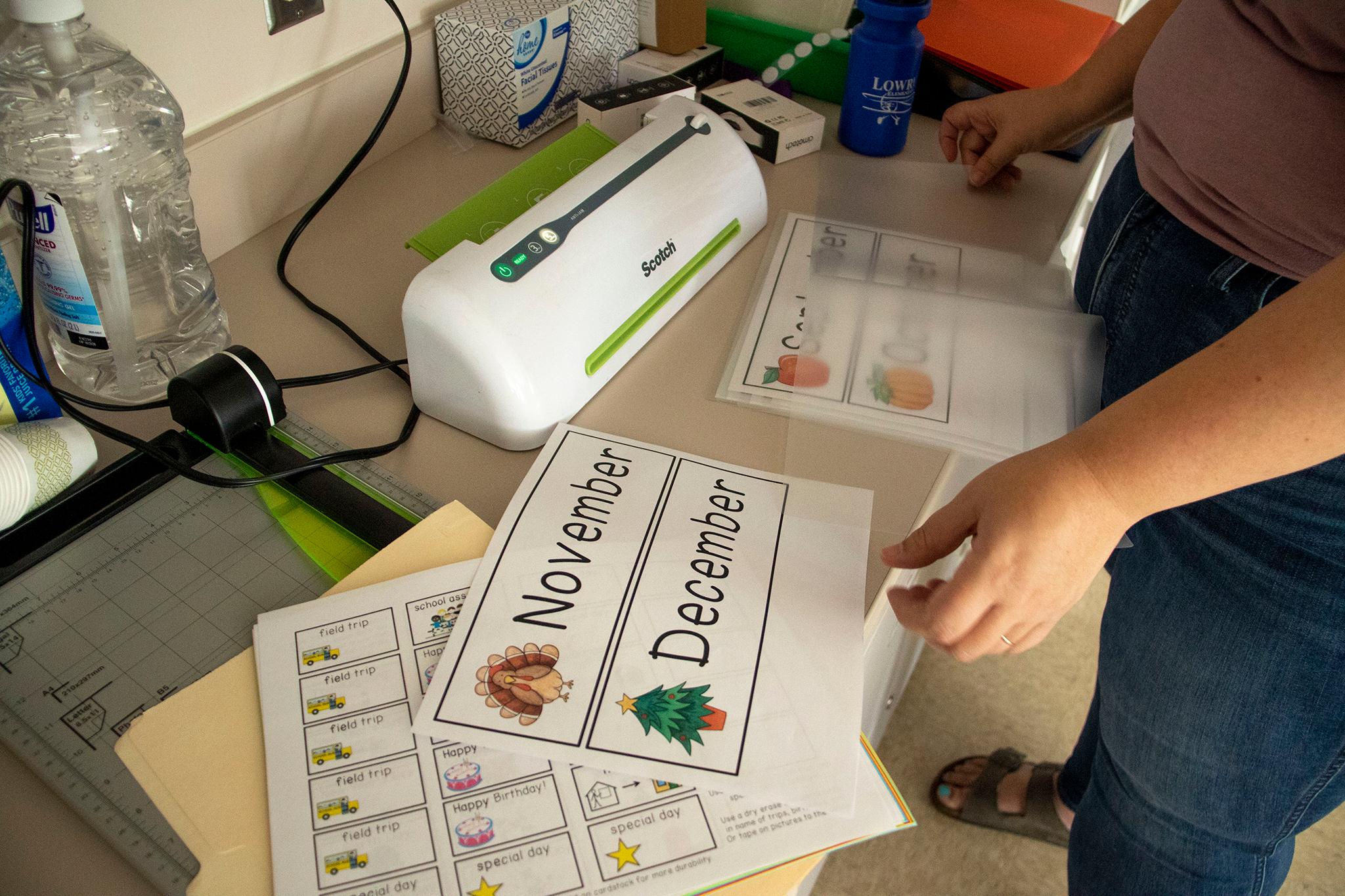

Games, markers and glue need to find their way back to their rightful cubbyholes. Computers need resetting. There is a lot to laminate.

COVID forced everyone at Denver Public Schools to learn from home during the 2020/2021 school year. Kids were mostly back in classes last year, but things were still a little sideways. She was more than ready for summer break, hence the rush that left things less than organized.

Her colleague, Alexis Lopez, said Monday will be kids' "first post-COVID year," though everyone knows that's not quite right. The virus might become a problem again. More so, the pandemic's less tangible impacts are still present in their universe, and both women know they'll be dealing with some developmental setbacks for a while.

Though she still carries a little trauma with her, Petrila and Lopez said they're mostly mostly looking forward to seeing their students.

They work with kids who need special attention in school. Their "affective needs" program is called When I Need Guidance and Support, or WINGS. The name is meant to reduce stigma around learning and behavioral disabilities.

There are only three kids assigned to Petrila's room this trimester, and all of them were in her class last year. Unlike their schoolmates, kids stick with the WINGS program from third to fifth grade. She's got some catching up to do.

"There's some anxiety, but I'm also really excited to see my kids," she said. "We want to see how tall they've gotten and what they did over the summer."

Petrila said her students had an especially tough time returning to the classroom last year, and she expects it won't take long to see if that's true this time around. But it seemed like kids were acting out across the entire school, and her anxiety was rooted in that broader disarray. Administrators were "putting out fires" everywhere, which meant she had less support than she's used to. She finished the spring trimester with a bit of burnout, and some of that lingered as she prepped for things to start up again this week.

"I've always read stories of teachers having the Sunday scaries and really stressing out. And up until the last two years, that hadn't been a thing I'd experienced," she told us. "In the last two years, that's changed drastically."

When everyone came back in person, Petrila said she and her colleagues were constantly reacting, which made it really hard to be the responsible adult in the room.

"Our nervous system was always in fight-or-flight mode. And like, I'm not a good teacher if I'm in my survival state, I can't regulate a kid. And that's how I felt like for most of the year," she said. "That's where I do start to have that anxiety of like, is this year gonna be different? Is it gonna feel different?"

Even if the vibe changes, there are plenty of other issues that need sorting out.

Lopez, WINGS' restorative justice coordinator, made it clear none of this is her students' fault.

"The kids are gonna be great. We will be great. Our team will be great. It's never those things," she said. "It's like the things above us that we can't control that make me nervous."

Lowry Elementary's leadership has changed a few times in the last year, since their usual principal is on leave. It's always a process to adjust to new leadership. Fortunately, Petrila said this year's interim leader has had a steadying influence on staff.

Then there are things further up into DPS management and beyond, systemic problems in both education and society, that give them pause.

First is compensation, which has been a sticking point in negotiations between the district and the Denver Classroom Teachers Association, the union that went on a very visible strike in 2019. Petrila spends some of her time outside of class on DCTA's negotiating team, hoping to move the needle on salaries, hiring and hours. She estimates she works about 12 hours overtime every week, which is not unusual.

Second, this difficult pandemic economy is also seeping into her classroom. While Petrila says her school supplies her basic necessities, the extra stuff she relies on, like lamination sheets and extra snacks, have cost a lot more. Like a lot of teachers in the district, she's had to ask friends and family to help pay for the items that makes her job easier. This year, the bill was a little higher than normal.

The inflation issue is impacting students, too. Madi Perry, a calculus teacher at DSST: Green Valley Ranch High School, told us she signed up for an Amazon wishlist for the first time this year. She mostly worried her students' families would struggle to afford the items on their back-to-school shopping lists.

"I offered folders yesterday, and way over half the class came up and took them from me," she told us. "Everything I bought has been used. I felt like I was totally right about that."

Perry also said "massive dips and declines" in academics, which stemmed from the learn-from-home era, are still super apparent. She and Petrila are working to deal with that, but they need to handle the parallel mental health problems first. Perry told us she's sent more kids to her in-school social worker and psychologist than ever before.

For Petrila, all of this is evidence of longstanding problems that became impossible to ignore during the pandemic.

School systems like DPS have long prioritized performance, measured by standardized testing, over the social and emotional skills she said must come first.

"This idea that we're somehow going back to normal is laughable to me, because there is no going back. The pandemic was shining a spotlight on all these inadequacies in our system. And to say, we're gonna go back means we're going to ignore those and not address them," she said. "Everyone with decision making power is saying, 'No, no, it's fine. It'll go away.' But it won't, it just keeps snowballing and getting bigger."

The blind spot, she added, is one reason why more and more seasoned teachers have begun to consider leaving the district. The city's high cost of living also doesn't help. DPS is short about 150 teaching positions this year; though that may not be unusual, Petrila said she is seeing new pressure.

"Some of the most passionate teachers are considering leaving the profession or leaving DPS in a way that I've never experienced before," she told us.

But she and her impassioned colleagues have trouble pulling themselves away, no matter how existentially stressful the job can be. She lives for the individualized care she crafts for each kid. The trans-Atlantic travel guide the airplane enthusiast, her "little love," put together as an exercise in writing, math and design. The calendars and posters her kids will help stick to her classroom walls with this week. The sometimes slow, sometimes sudden spurts of maturation she helps foster as each inches closer to middle school.

"It's where my heart is, for sure. I think not every person has the patience and ability to like depersonalize some of these really huge, scary behaviors, so like I have a calling to it and I really enjoy the work," she said.

But as she got her room in order, she said should couldn't say if she sees herself in this position forever. Calling or not, there's a lot to contend with now, more than ever.