Denver is on track to have more traffic deaths this year than in 2021. According to city data, 68 people have died from traffic collisions as of October 2, whereas, by the end of September 2021, that number had reached 57.

City officials have talked a lot about working to decrease traffic deaths in recent years, but at Thursday's budget hearing on transportation, many agreed it's not enough.

"It's a challenge in every single council district in the city and county of Denver right now," said Adam Phipps, executive director of the Department of Transportation and Infrastructure (DOTI), at the hearing. "Half of those fatalities are our more vulnerable road users, and we have an obligation as a city and as a department to continue to do all that we can to increase safety."

In 2021, council passed an ordinance lowering the speed limit on neighborhood roads from 25 to 20. Then there's Vision Zero, a program the city launched in 2017 as part of a national partnership that seeks to end all traffic deaths by 2030.

Instead, traffic deaths have trended in the other direction. When the city launched Vision Zero in 2017, fatalities were at 51. They reached a high of 84 in 2021, or a rate of around seven per month. In 2022 so far, that rate is at around 7.5 fatalities per month. If accidents continue at that speed, the city could see around 90 traffic deaths this year.

Phipps called the lack of progress on Vision Zero "unfortunate," and "a challenge nationally."

It's a problem throughout the country. While accidents decreased at the height of the pandemic with fewer people on the road, they've since climbed back up.

Denver Streets Partnership, a coalition of groups working towards safer streets, has been keeping track of the program's progress throughout the years.

"We are definitely headed in the wrong direction," said Jill Locantore, executive director of Denver Streets Partnership. "It's been a lot of spot improvements, focused on a particular intersection, or a small segment of road, and doing some quick and inexpensive things like adding paint and bollards."

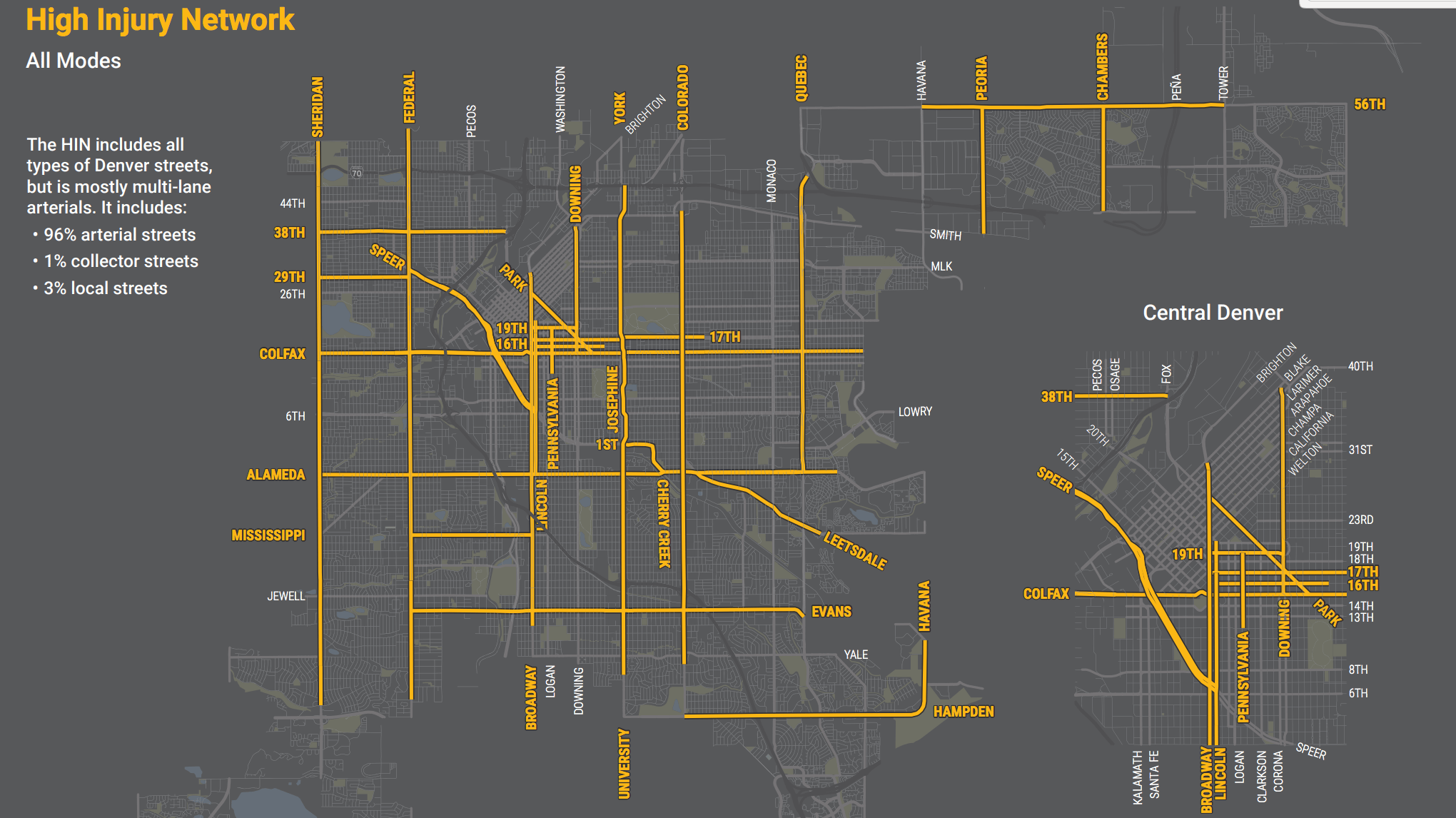

Locantore said these spot treatments are important and do succeed in decreasing crashes, but that to achieve larger goals, the city needs to focus on bigger change at high-risk areas like Colfax Avenue and Speer and Colorado boulevards.

"The key to doing that transformation that's been missing so far is a significant investment in improving transit on those corridors," Locantore said. "We just need a fundamental transformation of the corridor as a whole."

The original plan had the city designating $2 million towards Vision Zero for the first two years, and then $3 million from 2020 through 2023. Next year's proposed DOTI budget has around $2.3 million devoted to Vision Zero, but DOTI spokesperson Vanessa Lacayo said that number doesn't encompass all the city's funding towards road safety initiatives, such as funding for expanding bike lane access.

"There's a lot of other projects... where those ultimately are geared towards that vision zero goal," she said.

The program was meant to run as a five-year plan to implement safety measures like slow zones and reduced speeds. With fatalities on the rise, Phipps said the city plans to continue partnering nationally toward its goal of zero traffic deaths.

"We need to get out of this mindset of the single-occupancy vehicle," he said. "Folks need to change behavior. When you look at where these fatalities occur, how they occur and the incidents that lead up to it, we need to put our phones down, we need to make better decisions around drinking and driving."

Mayor Michael Hancock said he wants to see more action on the state level. The state Senate passed a distracted driving bill in the spring, but it stalled in the House. Proponents of the legislation said it would promote safety, but critics worried about introducing more policing on the roads.

"I struggle with understanding why we're not able to advance that bill and hopefully save lives and serious injuries on our streets," Hancock said.