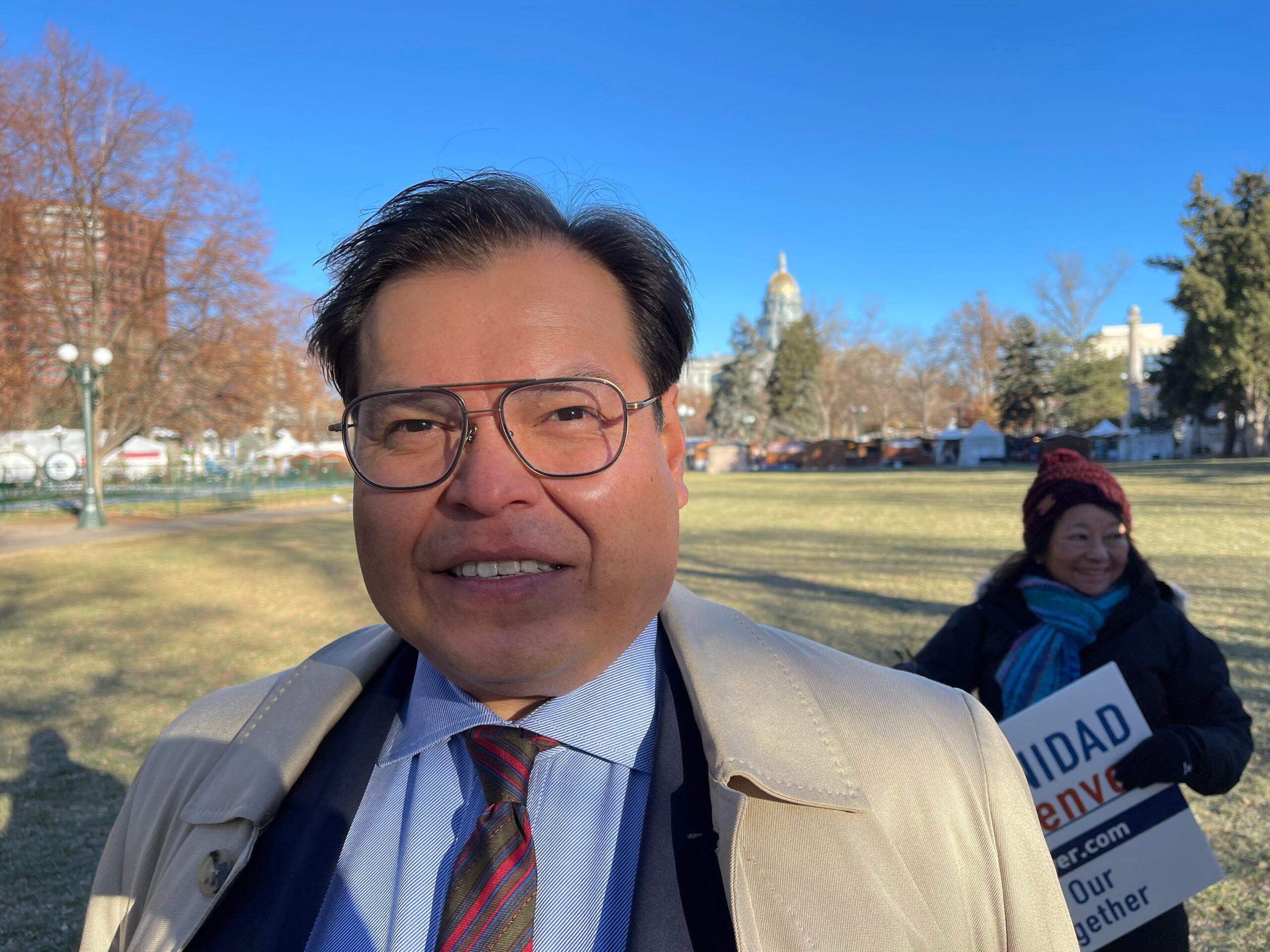

Standing in front of the Statehouse, mayoral candidate Trinidad Rodriguez told a small crowd of supporters he is ready to declare a state of emergency over homelessness in Denver.

Something about the city's response to homelessness isn't working and things are getting worse, he said. For Rodriguez, who has known people who lived without shelter and struggled with addiction, that's unacceptable -- not just for businesses but also for people experiencing homelessness and mental health issues.

"Part of my dedication to this cause comes from my personal experience with loved ones who have battled housing insecurity, addiction, and mental health disorders," he said. "It also helped me develop my proposal with an understanding and compassion for the challenges that our people are facing at an individual level."

When he was 11, he realized his godfather was both homeless and struggling with addiction.

"I remember the first hope and wish that popped into my head for him was, wherever he is, whatever city that he's in, that there is someone there who would protect him from himself and anyone who would do harm to him when he's vulnerable," he said.

The candidate's hope is that he's able to provide that kind of protection to the chronically homeless in Denver.

Rodriguez has spent 25 years of his career working to address homelessness through the Denver Housing Authority and as a board member at the Downtown Denver Partnership and the youth homelessness provider Urban Peak. He's been a member of Denver's Housing Advisory Council and served on the taskforce for Blueprint Denver, a master plan for the city.

"I believe the catastrophe on our streets is principally driven by a series of health crises -- not affordability in our city," he said.

The city's strategies for addressing the issues of addiction and mental health of those living on the streets simply aren't working, he said. Deaths among people experiencing homelessness are up, and violence is rising.

"Downtown is a shadow of its former self, having been overtaken by people in crisis pursuing their drug misuse, tormented by mental disorders, and by those who prey upon them, presenting serious safety problems," Rodriguez said. "Employees of our downtown businesses cite safety concerns among their principal reasons for not returning to their offices."

The city's attempts to manage homelessness have been long and complicated. One of Mayor Michael Hancock's signature efforts in his first term was the passing of an urban camping ban. The city has seen a dramatic rise of unsheltered homelessness since its passage.

The community around Union Station has wrangled with the Hancock administration's approach to homelessness and mental health issues on the streets. Some residents have demanded a more muscular police response. Downtown condo dwellers have advocated to shut down a hotel where unhoused people vulnerable to COVID-19 were living. Businesses in Capitol Hill and other neighborhoods have put boulders and fencing on their properties to deter people from camping in front of their buildings.

Rodriguez, who donated to Hancock's mayoral campaigns from 2013 to 2019, proposed joining downtown business leaders in their plans for addressing safety and homelessness. That follows Hancock's actions, including a recent compassionate crackdown on crime, with help from the Downtown Denver Partnership, the U.S. Attorney's Office, Colorado's Attorney General and the mayor.

But if elected, Rodriguez plans to take things a step further.

"As Mayor, among my first acts will be to declare a state of emergency regarding unhoused people living on Denver streets," said Rodriguez, who was a financial backer of the Hancock campaign.

Doing so, he would exercise powers from the Colorado Disaster Emergency Act and Denver Charter that would free up emergency funding to address the issue.

"With this expanded authority I propose to, first of all, build a temporary field treatment center with the help of local, state and federal resources that are appropriate in a state of emergency, actually employing a lot of the strategies we developed as we prepared for a catastrophic COVID surge."

Kyle Harris / Denverite

He would move the mayor's office to the field treatment center as long as there was "any single person receiving treatment," he said.

He plans to harness state and federal resources to pay staff, including medical professionals, to admit people into medical care who are a danger to themselves or others. That could be voluntarily or involuntarily. He also wants to push state lawmakers to enable involuntary holds on people in need of mental and substance addiction treatment.

"We will have a high ethical burden to ensure our approach is humane, and we will satisfy it," Rodriguez said.

He would open navigation centers, akin to similar ones in Houston and the Bay Area, where people can be connected to treatment.

"I support the transition of people when they are stabilized from this initial treatment to the ecosystem of providers in our community to ensure additional phases of healing and recovery with providers and the offering of more voluntary options," he said.

He believes this approach -- which echoes New York Mayor Eric Adams' controversial plan to involuntarily hospitalize mentally ill people who appear unable to care for themselves -- will help people experiencing homelessness and Denver's neighborhoods alike.

"What success will look like is that unhoused people will get compassionate assistance regardless of where they are in their journey -- voluntarily or involuntarily," he said. "Our neighborhoods will see visible improvements in public health and safety conditions surrounding street homelessness."