High-tech solar panels are increasingly common fixtures on homes now. But in the 1960s and 1970s, one Denver-based architect was ahead of his time by pioneering the design of environmentally conscious homes that maximized the use of Colorado's very available sunshine.

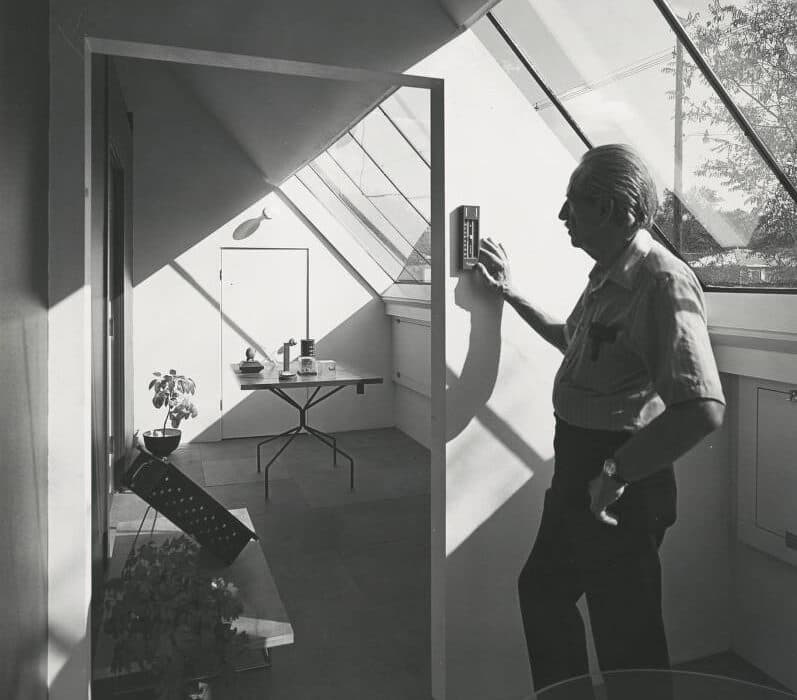

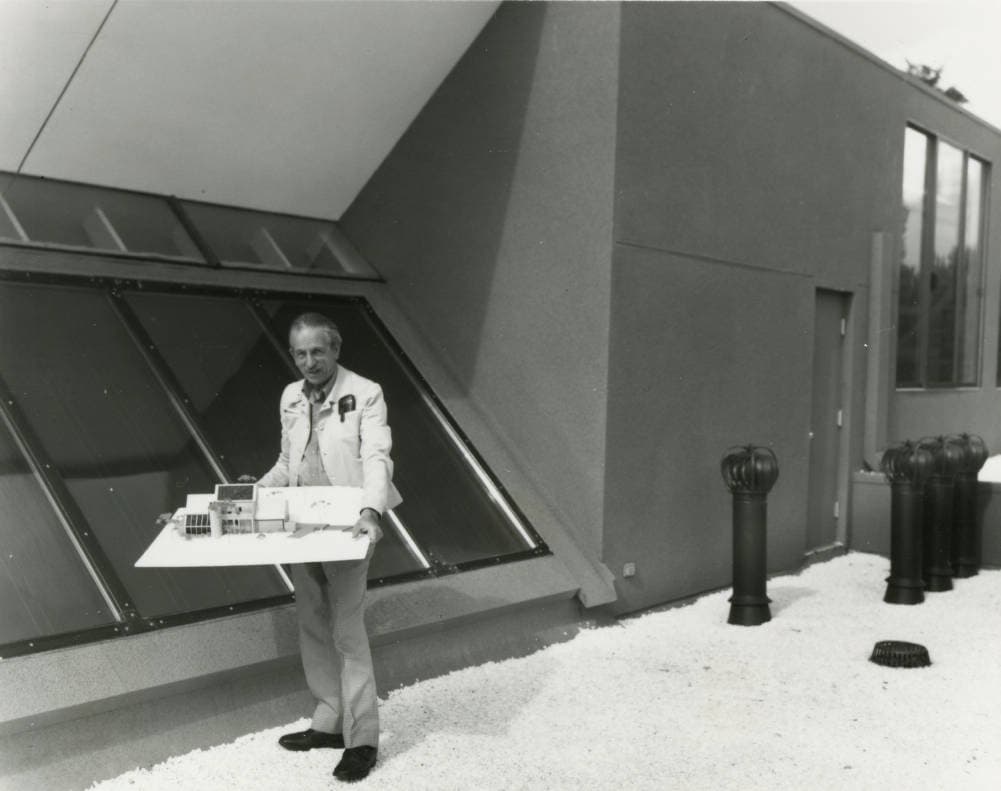

Richard Crowther became known for early solar architecture and designed many buildings throughout Denver, including multiple theaters and homes, giving him the chance to experiment with environmental design. Today, many of those buildings have been knocked down, sometimes with structures that aren't as energy-efficient taking their place.

Now, his former home is on the chopping block. Crowther died in 2006, and his home at 401 Madison St. in Cherry Creek fell into disrepair. Private developers bought the building and marked it for demolition in September, which led a group to submit an application to preserve the building as a historical landmark.

Denver's office of Community Planning and Development, which considers landmark applications, recommended approval. But an inspection of the property requested by the owner found rotting wood, mold and many safety issues, ultimately recommending demolition. And neighbors overwhelmingly see the home as an abandoned eyesore, welcoming redevelopment that could fetch high prices and fit in on the block. On Monday, City Council will hold a public comment session and vote.

For many historians and architects, it's an iconic building.

The home was built in the 1970s in Late Modern style, horizontally oriented with deep-set windows and lots of concrete. It's not flashy, and it stands out among the many large, multi-story homes on the street.

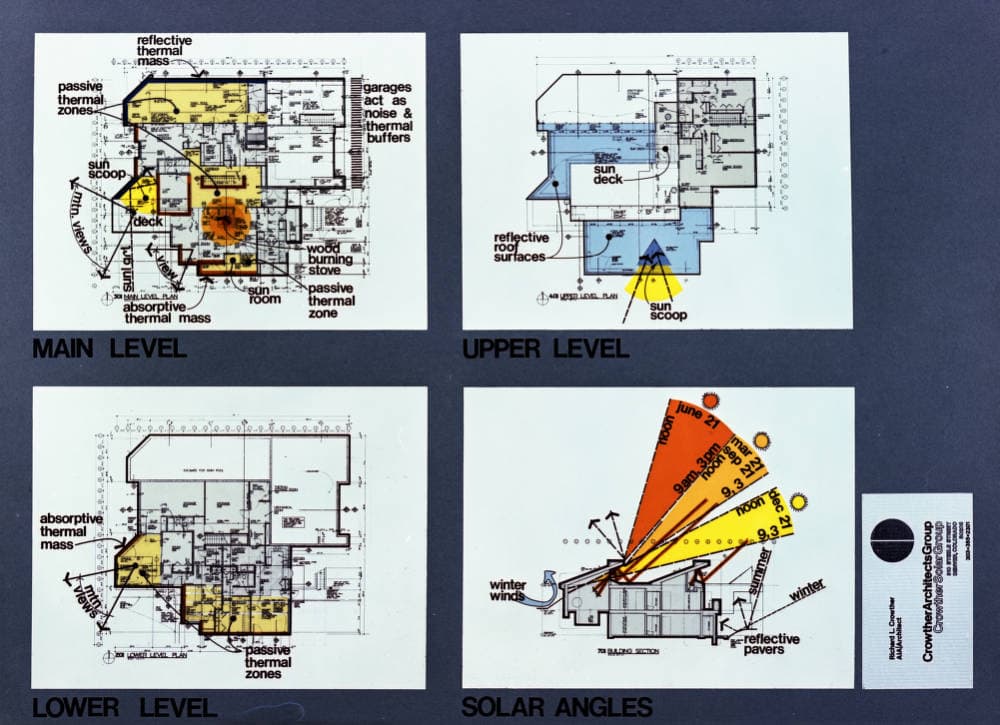

"The 401 Madison residence is listed among Crowther's most important designs and embodies his guiding fossil fuel-free design philosophy," wrote Tom Hart, Michael Hughes and Alan Gass in their application for preservation. "Although not his first passive solar design, it was completed at the height of his architectural career, served as his home and laboratory until his death in 2006, and is thus a significant example of his work."

The home has been featured in books and journals about environmental design and Mid-century modern architecture. Crowther designed the windows to capture sunlight in some areas and chose building materials to redirect heat in other areas. As the environmental movement gained steam in the 1960s, he became a leader in early green architecture.

For architects like Hart, it would be ironic to knock down the home, given the energy it would take to demolish and build something new. Meanwhile, the ruins would end up in a landfill. And beyond the environmental aspect, Hart thinks it's important to preserve this history.

"These structures make each place unique," he said. "Any kind of solar energy efficiency kind of thing started with people like that [Crowther]. And so it tells a story of our past, Denver's past, Cherry Creek's past."

But the building has fallen into disrepair, and the application for preservation has been met by overwhelming opposition by Cherry Creek residents.

Overgrown weeds surround the property. It has broken windows and the roof leaks. Graffiti's been tagged on it.

Residents say people experiencing homelessness have sometimes camped there over the years; a family of foxes moved in at one point; and it's been used as an unofficial skate park.

Plus, a November report by Barton Consulting Services, commissioned by the owner, found corroded metal, rotting wood, damaged insulation and many other safety issues and structural problems. The report said the building was unsound, and recommended demolishing the majority of the building.

Through a public hearing, letters, signatures and voicemails, 62 people opposed preservation of the building, compared to eight supporting the proposal. According to application materials, owner MAG Builders, also isn't interested in preservation.

MAG Builders did not respond to Denverite's request for comment.

"We are opposed to any attempt to have this property approved for 'historic designation' especially given the timing of this request after decades of this property been vacant," wrote community members in a petition signed by 33 people living within a block of the building. "The present condition of this lot is an eye sore and has been used for inappropriate activities."

Many people in the neighborhood wrote that they appreciate local history, but that Crowther's home is too far gone, left discarded for almost 20 years. Preservation, they feel, would prioritize the desires of a few over what most people in the neighborhood want.

Neighbors also expressed frustration at a push to preserve the building only after a developer paid a high price to turn the property around by redeveloping. Hart says he and his fellow applicants had to act fast once it was marked for demolition.

"The gentlemen that have submitted the application do not live in the neighborhood and seem to have some rosy image of the property when it was in its prime condition," wrote resident Doug Macnaught in a public letter. "It is so far removed from that position today to make it unrecognizable. No one has offered to purchase and restore it. It does not fit with any other structure in the neighborhood."

For some residents, it's just ugly. One person called the home "the CIA Bunker of N Cherry Creek," "reminiscent of the German defense structures built on the cliffs of Normandy." People have called it "a brutal slab of concrete" and "heavy, oppressive, dark and dungeon-like, more resembling a 1950s-era bomb shelter or maximum security mini-prison."

Hart, one of the applicants, is not swayed by current aesthetics, noting that the kinds of buildings people have considered ugly changes over decades. He pointed to the Molly Brown House, which was almost demolished when Victorian houses fell out of style and underwent a $2 million renovation a few years ago.

He's sympathetic to the disrepair in the middle of the neighborhood, but said he thinks the building can be turned around.

"It takes somebody to step up to do it," he said. "In the meantime, the city, the neighborhoods, should not allow these structures to be demolished by neglect."

The question is, who will step up?

Public documents indicate that owner MAG Builders is not interested in renovating or preserving the existing building. If the structure wins historical designation, neighbors worry no one will be interested, especially given the extent of the damage, leading the building to sit in disrepair in the middle of the neighborhood for years to come. The fate of Crowther's home now lies in the hands of City Council, who will vote Monday after a public hearing.

District 10 Councilman Chris Hinds represents the area where the Crowther house sits. He said City Council takes on a quasi-judicial role in cases like this, and that transparency and due process will be key in Monday's public hearing and vote.

"Part of the reason why it's important here is this is not only the historic context, but also it involves money," Hinds said. "The developer bought this property with the expectation that they were going to get to do things, and then based on this conversation, the things that they thought they were going to get to do may or may not come to fruition. And even just having a conversation which delays, costs money, and it creates uncertainty, and uncertainty costs money."

Editor's note: This article has been updated with the correct spelling of Alan Gass' name.