Michael Hancock was on a bicycle in downtown San Francisco.

It was a warm, sunny day in the summer of 2015. The Denver mayor and dozens of other local officials and business leaders were on an "urban exploration" trip, looking for ideas they could bring back to their city.

"It was a good ride," Hancock said, remembering bike-specific infrastructure like traffic signals that made it feel more comfortable.

San Francisco had been on a tear expanding bicycle lanes, and just the year before, became one of the first U.S. cities to adopt the "Vision Zero" goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries primarily through redesigning city streets. It was likely on this trip, Hancock said, that he first learned about Vision Zero -- and he thought it made a lot of sense.

"That's why I said, 'you know what? That's the vision. Let's establish that as the goal, and let's build our form and function around achieving that goal,'" Hancock said in an interview at his office last month.

Hancock's transportation planning staff was ready to meet the moment. A handful had already been pushing Vision Zero and multimodal transportation plans internally, albeit with little success.

"We were meeting about meetings," Rachael Bronson, a former multimodal transportation planner in the Hancock administration, said of her early Vision Zero efforts. "You get stuck in this spin cycle."

But by the time of Hancock's California trip, he and other city leaders were warming to transit, walking and biking as solutions to worsening traffic and climate goals as Denver's population grew. They drew inspiration from more pedestrian-friendly and transit-forward cities like San Francisco -- and Vision Zero complemented that new direction.

Soon, Bronson said, Denver's Vision Zero efforts took on new urgency. Hancock's administration publicly committed to Vision Zero in 2016. An action plan followed that gave Denver a 2030 deadline to eliminate traffic deaths.

"It felt so great," said Bronson, who helped write the plan. "I was so proud of the work we did."

Much more work has been done in the six years since: Hancock recently celebrated 125 miles of new bicycle infrastructure; the city lowered its speed limit to 20 mph on neighborhood streets; it installed other traffic-calming measures and updated traffic signals in trouble spots.

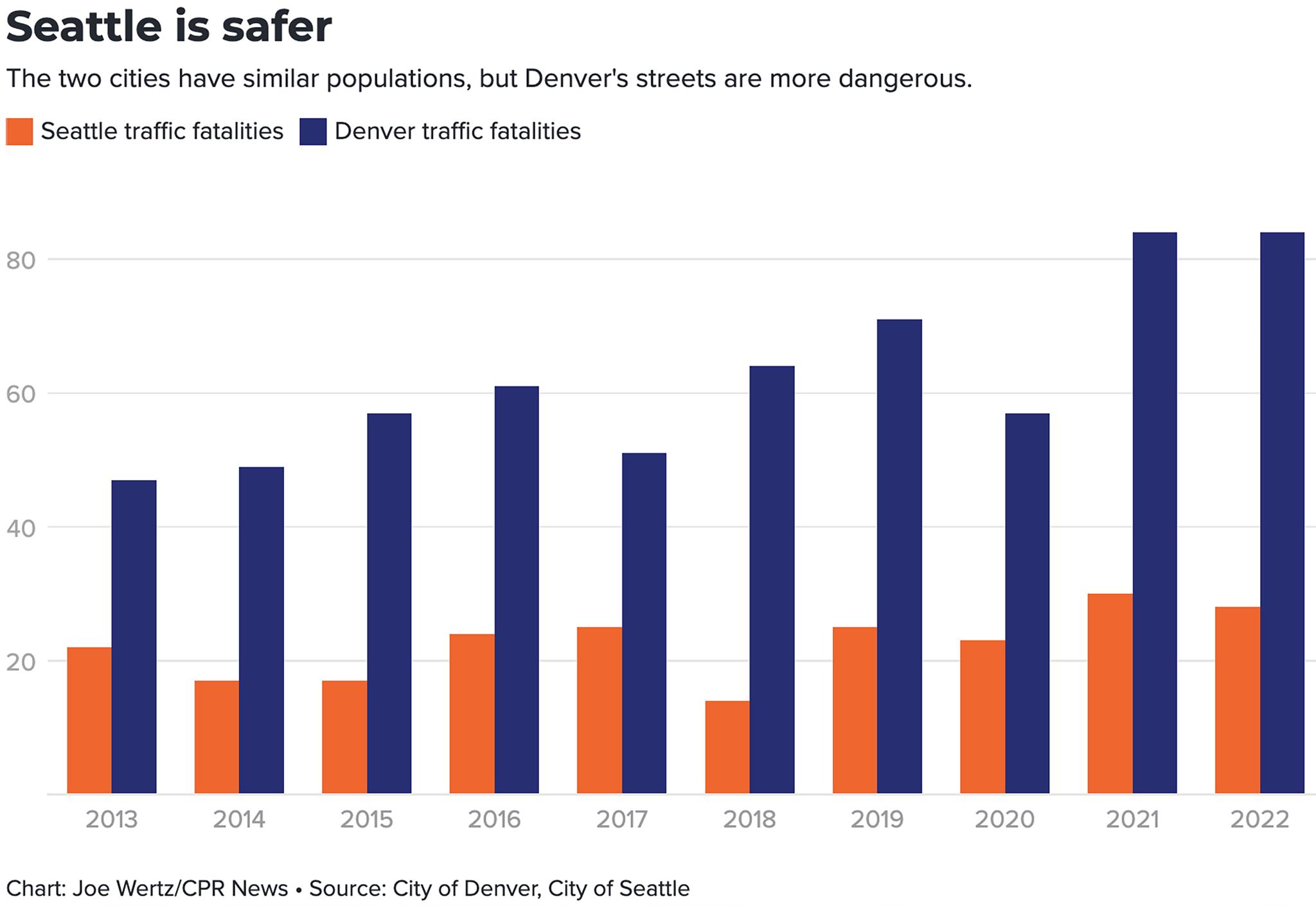

Despite those measures, Denver's streets are deadlier now than they have been since 2000.

More than 400 people have died in traffic crashes, and there've been more than 2,000 crashes causing serious injuries in the six full years since the city committed to Vision Zero, city data show.

Denver's traffic fatalities hit a two-decade high in the last few years. In 2021 and 2022, the most recent years for which there is complete data, the city recorded 84 fatal crashes each year.

Fatality rates, which account for Denver's population growth, are the highest since 2004. Pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists are all over-represented in fatal crashes, too.

"We knew it would get worse before it got better," Hancock said, because the city's population was growing, and his administration was attempting to change a decades-long car-centric culture. "We didn't get into this with rose-colored lenses. It wasn't going to happen overnight, and certainly we've seen that it's not happening overnight."

A handful of factors outside of Hancock's direct control have likely contributed to the rise in certain types of traffic deaths, too.

Larger, heavier vehicles, for example, are increasingly popular and more deadly to people outside of them. They are now involved with most crashes that kill pedestrians and cyclists in the Denver region. Hancock has also repeatedly cited distracted driving and cell phone use for some traffic crashes, an assertion that research supports.

Still, the Vision Zero philosophy, born in Europe, where traffic deaths are much lower than in the U.S., that Denver subscribed to puts the onus on the city itself to make its transportation system safer. If governments design their streets safely and enforce lowered speed limits fairly, for example, those systems can help prevent inevitable human errors from being fatal.

That runs contrary to the century-long U.S. tradition of blaming individual road users for crashes -- especially the most vulnerable.

"Forcing reduced speeds on our city streets through design changes and enforcement is one of the most impactful Vision Zero actions that can be taken," city officials wrote in their most recent plan.

But speed enforcement has fallen sharply over the last decade. And with few exceptions, the city has avoided making transformational design changes to its fastest, busiest and deadliest streets that the city's own analysis acknowledges account for more than 80 percent of deaths and serious injuries.

Asked why he didn't enact more sweeping changes to Denver's most dangerous streets, Hancock said the question was "above my pay grade" and deferred to his engineering staff.

"The reality is if the department studies it and the engineers say, 'Mayor, we believe this is in the best interest of safety and obtaining the goals that we want to obtain,' then I usually endorse it," he said.

Some dangerous roads, like Federal Boulevard and Colfax Avenue, double as state and federal highways and are outside of the city's direct control, he pointed out. He also cited various new bike lanes that ate up parking spots or vehicle lanes, including the long-awaited one on Broadway, as controversial projects he's backed.

Jill Locantore, executive director of the Denver Streets Partnership and the city's foremost street safety advocate, called that response "a little bit of a cop out."

"Where I think the administration was weak was in taking on the more challenging aspects of implementation," Locantore said. "We need fewer streets designed like highways," she continued. "We can get there if we agree as a community that that's the kind of city we want to be. But it does require us to become a different city than we are today."

Alita and Dan Anderson rebuilt their lives near one of those streets that double as a highway. It ripped them apart, too.

They had been living with Alita's mother but ended up on the streets after her mother was diagnosed with cancer and lost her house. So on a cold, rainy day in 2018, they called Alita's uncle Tim Campbell and asked if they could crash at his place near West Colfax Avenue.

"He let us stay," Alita recalled, adding: "We got really close."

Everything changed on Sept. 11, 2020. Campbell woke up early to catch the West Colfax bus to an appointment at Denver Health. Later that morning, Alita got a phone call from her mother: A car had hit Campbell and he was in critical condition. Dan sensed that it had happened on West Colfax.

"It was like highway central to me," he said. "I probably got close to being hit five or six times just in the two years that we were there."

He and Alita rushed to Colfax and quickly recognized Campbell's flattened wheelchair.

"All I could do was scream," Alita said, adding: "I felt like I was the one hit by the car. It was like all the air was knocked out of my body."

Paramedics took Campbell to Denver Health. Initially, Alita said, he was awake and cracking jokes with them. Then, exactly 40 minutes after the crash, he was pronounced dead.

"He had a massive heart attack," Alita said. "His heart just couldn't handle the impact."

The impact came from a Subaru traveling at 42 mph -- well over the posted speed limit of 30 mph. The driver ran a red light, striking Campbell in the crosswalk. Video footage showed Campbell crossing West Colfax before he had the walk sign -- Alita and Dan surmise he was trying to catch his bus.

Dan and Alita hope the city will reshape the road to slow traffic.

"If I were still driving today and I knew that I was going to have to go a little slower so that somebody could live, I would be fine with that," Alita said.

For one day, drivers had no choice but to drive slowly down West Colfax.

West Colfax, between Federal Boulevard and the Denver-Lakewood border at Sheridan Boulevard, is in many ways typical of the city's most dangerous streets. In Denver's earliest decades, it carried streetcars and was lined with small storefronts.

Then, after World War II, the streetcars were ripped out, and the road was widened to accommodate traffic from the developing western suburbs at the expense of sidewalk space. Other local streets went through similar transformations in this era. Residents and businesses have lived with the roar of traffic -- and its associated dangers -- ever since.

That is, except for one day in 2015.

The neighborhood business improvement district sponsored a complete reimagining of one block of West Colfax. They narrowed it from four lanes of traffic to two and temporarily installed wider sidewalks, tiny parks, medians with vegetation, rainbow-colored crosswalks -- even a protected bike lane on Colfax itself.

"It was much quieter, traffic was moving much slower," said Dan Shah, executive director of the West Colfax Business Improvement District, adding: "It was really inspiring."

The demonstration was meant to show residents what West Colfax could be someday -- and get their feedback on it. Shah collected some on big blackboards -- and it was all positive.

"OMG - CAN WE HAVE THIS ALL THE TIME?!?" one person wrote.

That day helped build support for changes to West Colfax. But those plans don't amount to a transformation.

West Colfax, like many busy four- and six-lane arterial streets in Denver, is part of the city's "high-injury network" -- corridors that see a disproportionate number of serious injuries and fatalities. Seven people were killed and 21 seriously injured along the corridor in 2019 and 2020.

The Colorado Department of Transportation, which owns the road, has acknowledged the problem. In 2020, the CDOT and the Denver Regional Council of Governments granted Denver and neighboring Lakewood $10 million each for safety fixes through its "Safer Main Streets" program, which has since been expanded to cover the entire state.

Lakewood transportation officials are using the grant money to narrow West Colfax from three lanes in each direction to two to accommodate new sidewalks. The federal government says such "road diets" are proven ways to reduce crashes.

Changes are coming to the Denver side, too. The street will have new medians with vegetation that will replace the center turn lane at many intersections. Engineers say those will prevent drivers from hitting pedestrians at intersections. Curb extensions will also reduce the distance pedestrians must cross, and public transit buses will get priority at intersections.

The final design, however, keeps the speed limit at 30 mph, retains its two traffic lanes in each direction, and drops the wider sidewalks and protected bike lanes.

City officials say cost was one reason wider sidewalks were left out. There isn't room for bike lanes, they say, because West Colfax will eventually be a bus rapid transit corridor -- meaning it may have bus-only lanes someday. A CDOT spokesperson said the city never proposed bicycle lanes; the city instead built them on nearby sidestreets.

City traffic engineer Emily Gloeckner said they are trying to make dangerous arterial streets like West Colfax safer while preserving their ability to carry tens of thousands of vehicles daily.

"We have to be realistic about the fact that some of these roads carry a huge amount of vehicular traffic," Gloeckner said of Denver's arterial streets generally. "We still need to be able to accommodate those people that are moving in vehicles."

The toned-down reimagining of West Colfax has the support of business owners along West Colfax, Shah said. They want their shops, breweries and restaurants to be as accessible and have adequate parking.

"Our position is not one of, 'We have to be fully given over to the pedestrian,' " Shah said. "We have to balance that with access for the customers [who drive]."

Smaller changes made to the corridor appear to be helping: As part of its "rapid response" program to crashes, the city retimed traffic signals in October 2020 to make it easier for pedestrians to cross West Colfax. Fatal crashes and serious injuries dropped significantly afterward.

But Vision Zero's goal is to eliminate, not just reduce, deaths and serious injuries. A look at one of Denver's peer cities suggests wide, fast roads themselves are the problem.

Seattle and Denver have similar populations of just over 700,000. Both cities adopted Vision Zero at about the same time, and both have struggled to meet their lofty goals. And both cities say in their Vision Zero documentation that arterial streets are the deadliest.

But the two cities diverge in some very important ways: Seattle's traffic fatality and serious injury counts tend to be much lower than Denver's. Bradley Topol, capital projects coordinator for Seattle's Vision Zero program, pointed to that city's denser, smaller footprint with far fewer miles of arterial streets as a key reason for the difference.

"The best conclusion I can draw between Seattle and Denver is that while populations are similar Denver has many more miles of arterial streets (especially multilane arterials) and that leads to greater exposure," Topol wrote in an email.

Seattle has also been more aggressive in lowering speed limits on dangerous arterial streets than Denver has. Seattle dropped the default speed limit on its arterials to just 25 mph -- and an independent study and a city analysis showed crashes and speeds both declined.

That was a good first step, said Gordon Padelford, executive director of the advocacy group Seattle Neighborhood Greenways.

"Changing out speed limit signs is helpful," he said. "But it's only marginally helpful."

Street redesign, including road diets, are a better way to force lower speeds, Padelford said. Seattle has "excelled" at those in the past, he added, even though they are typically unpopular with motorists and local business owners.

"Intuitively, that sounds like it's going to be a giant headache for everyone and it's going to take forever to get anywhere," Padelford said. "What ends up happening is that people are still able to get through, but everything is much calmer and safer."

Denver has effectively narrowed a handful of streets recently by turning vehicle lanes to full-time bus-only lanes on the Broadway corridor and some downtown streets. It will soon go even further on East Colfax when a long-planned bus rapid transit project will reduce vehicle lanes to one each in each direction.

Most of Denver's arterial streets, however, are as wide as they were when it adopted Vision Zero (some are even wider). The city, CDOT and regional planners all have plans for more bus rapid transit lines along arterial streets like Federal and Colorado boulevards -- even West Colfax someday -- which could yield more bus-only lanes that effectively narrow streets.

Whether buses get dedicated lanes will be decided on a corridor-by-corridor basis, said Ryan Noles, CDOT's bus rapid transit program manager.

"Our goal is not to make anyone's life difficult or make it hard to get anywhere," Noles said. "In fact, it's quite the opposite. We want to improve access and we see bus rapid transit ... as a way to do that."

On Federal Boulevard, bus-only lanes are likely only in sections where it can maintain two travel lanes for vehicles.

"To have Federal go down to one lane is not realistic," said Leslie Twarogowski, executive director of the Federal Boulevard Business Improvement District.

"I don't know that Denver's ready for that," she continued. "If we could first just slow down the speeds that would be fantastic. Let's start there."

Denver has lowered speed limits on a few sections of arterial streets it controls. Its latest Vision Zero plan calls for a citywide speed limit reduction on "all major streets" to 25 mph by 2028.

Any changes to speed limits on CDOT-owned roads like Federal and Colorado boulevards also requires a speed study and state approval. Denver has not requested any speed studies of state-owned roads within city limits since it adopted Vision Zero, the city and CDOT said.

Advocates say Hancock deserves credit but should've done more.

CPR News reviewed the private calendars of Hancock and his deputy chief of staff to gauge how much they prioritized Vision Zero. Their calendars show a peak of 20 Vision Zero-related meetings between the two in 2017. But they've had relatively few since then; Hancock did not have any between 2020 and 2022.

Hancock said he's received regular traffic crash updates from his staff and that the dwindling calendar schedule does not show that he lost interest in eliminating traffic deaths on Denver's streets.

"Once you lay down the values and the plan, it's time for [staff] to go and begin the process of implementing," he said. "They can sit in meetings with me all day, but they really need to go do the work."

Hancock deserves credit for committing Denver to Vision Zero, Locantore, the local street safety advocate, said. But she doubts he was fully bought into Vision Zero's systematic approach.

"It's about completely redesigning the system. I'm not sure the current administration fully internalized that," said Locantore.

Indeed, Hancock insisted that some responsibility still rests with the drivers, cyclists, pedestrians, and other users.

"We just try to design a system that raises awareness and creates opportunity for safe passage for everyone," he said. "But ... it's those thousands of thoughts and thousands of decisions every day that decide whether or not that system works."

Many of the city's safety-focused street redesigns have been effective, Locantore said. Their scale just hasn't been big enough to counteract the full scope of the problem.

Denver is not alone in its hesitancy to make large changes, said Leah Shahum, executive director of the Vision Zero Network, a national nonprofit.

"Cities are dipping their toe in this pool," she said. "That's really important and it needs to happen. But they need to jump in."

Redesigning streets for lower speeds is one thing. Enforcing limits is another.

Logan Rocklin's family and friends aren't exactly sure where the 34-year-old was going on his bicycle that night in December 2022. The Wheat Ridge resident had spent the day at a hospital with his wife, Hillary, who had just received a stem cell transplant meant to treat her leukemia.

He was crossing Sheridan Boulevard on West 38th Avenue -- two very busy, wide roads -- when a hit-and-run driver ran a red light and struck and killed him.

Rocklin's death, "just ripped everybody to pieces," said his brother-in-law Eric Elliott. "It pretty much destroyed them.

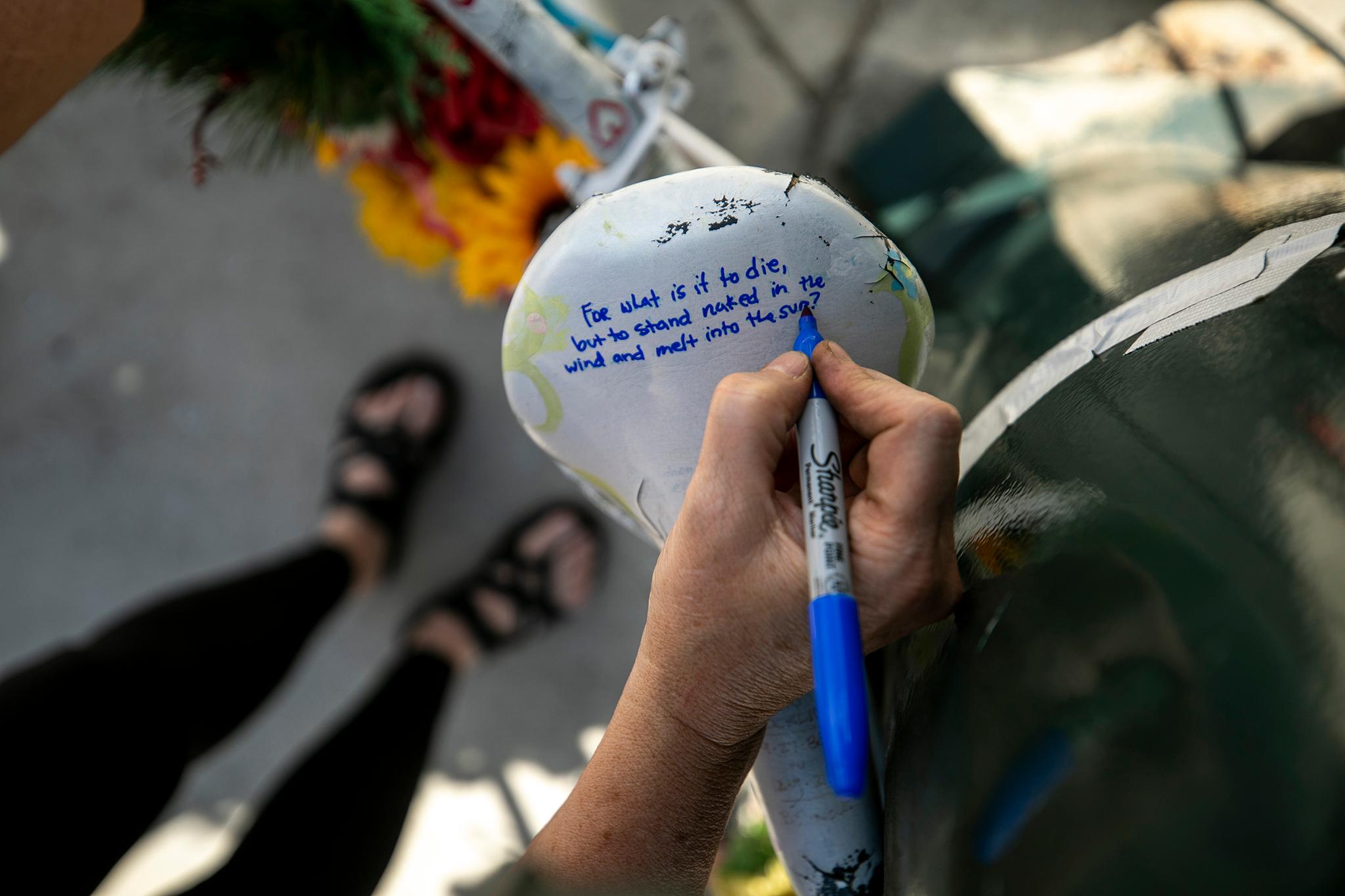

Elliot and other friends and family still occasionally visit it to freshen up the white "ghost" memorial bicycle they tied to a nearby traffic light. The thrifted bicycle is showing its age: the paint is chipped, the wheels are bent and the spokes are contorted.

"It's pretty hammered," Rocklin's sister Andy Morris said. "It's been run over twice ... We debated about replacing it, but we decided not to because it kind of makes a statement about the intersection and how dangerous it is."

Elliott said the coroner told him the driver that hit and killed Rocklin was traveling between 50 and 60 mph. That's well over the posted speed limit of 35 mph.

The case is still under investigation, and the Denver Police Department declined to comment on its specifics. Elliott and Morris suspect the crash was the result of road rage or street racing -- another car blew the red light and also did not stop -- and believe more enforcement, in addition to engineering fixes, is needed.

Most deadly crashes in Denver happen on high-speed streets. But speed limit enforcement has fallen precipitously in the last few years.

The best long-term method to reduce speeding, Vision Zero advocates say, is to redesign roads in ways that force drivers to slow down. But the federal government and the city's own original Vision Zero plan acknowledge enforcement is an important tool to reduce speeding.

"Traffic citations and crashes are directly correlated," city officials wrote in the mayor's last budget proposal. "When more enforcement activity is conducted, there are fewer crashes."

It appears that speeders are much more likely to get away with it now than at any time in recent memory: Enforcement levels have declined by nearly two-thirds in the last decade, even as speeding became the "new normal" in the pandemic.

Denver Police officers wrote nearly 60,000 speeding tickets in 2013 and 2014, according to data compiled by Denver County Court and confirmed by the police department. That figure slowly declined through the end of the decade before falling to only about 20,000 in 2022.

The department said it could not provide someone to speak to the enforcement data. In an email, department spokesperson Christine Downs wrote that, " ... it is no secret that staffing at police departments across the nation is down, Denver is no exception. DPD is hiring and training officers with the goal of adding officers to the Traffic section."

The city has increased its use of automated speed enforcement in recent decades, though, until very recently state law severely limited where they could be placed. That changed when Gov. Jared Polis signed a bill last month that allows cities, including Denver, to use them on arterial streets.

"We need help," said Gloeckner, the city traffic engineer. "We don't have the resources to be out there with a huge level of enforcement."

Street safety advocates generally support the increased use of speed cameras because they see them as a potentially less racist way to enforce traffic laws.

How Denver tries to make its streets safer will largely be up to its next mayor.

Mayor-elect Mike Johnston declined CPR News' request for an interview. During the campaign, he expressed support for things like automated speed enforcement, slowing traffic, cheaper transit passes, improving walkability, and more protected bike lanes.

"I think it's aggressive enough, and I think it's admirable, and I think we have to take it upon ourselves to make it achievable," Johnston said of Vision Zero.

Advocates like Locantore are hopeful Johnston will make street safety a top priority.

"It feels like we're starting in a very different place than we were 12 years ago," Locantore said of the incoming Johnston administration. "Non-car ways of getting around are very much a part of the conversation from the get go with this administration."

Another one of Johnston's marquee campaign promises -- to eliminate homelessness in his first term -- could also have an effect on the city's efforts to eliminate serious crashes and traffic deaths.

Tina Padilla was homeless when she died.

She was a popular, pretty and smart girl who grew up in the Quigg-Newton public housing projects on Denver's northwest side, said her mother Mary Ann Romero. Then, her 14-year-old little sister Gina was killed at a party by a stray bullet. After that, Tina started drinking and struggled with drugs. Eventually, she ended up in prison and lost custody of her three children.

"She was a big part of our lives when we were younger," said her daughter, Heather Escobedo. "She was writing to us constantly when she was in prison or if she was in a halfway house."

Padilla often lived in motel rooms on Colfax and used buses to get around town. Every so often, Romero would get a call from her daughter, drunk, and go pick her up.

"She'd stay for days. We'd just go places -- Goodwills, or walk the park," Romero said. "And there's times that she didn't come around for days and I didn't know where she was."

Early one morning in August 2017, Romero got another call. Padilla had been hit and killed by an intoxicated driver while running across South Federal Boulevard late the night before. She'd just left a liquor store and was trying to catch a bus to see her boyfriend, Romero said. Her body flew over the car and, Romero said, traveled about 30 feet.

It was one of dozens of pedestrian deaths in the mid-2010s along Federal that led a former CDOT executive to describe the road in 2019 as a "bloodbath."

Romero said her faith in God helped her survive after both Tina and Gina were killed. Sometimes, though, when she's running late for church, she has to drive by the site of Tina's death on Federal. She said she numbs her brain, turns up worship music, and sings along.

Every now and then, Romero said she sees her daughters in her dreams. Tina has pretty, curly hair and isn't drunk. Both girls look happy and at their very best.

Those visions help Romero keep her faith, she said, and hopeful for a better life after this one.

"I want to see them again," she said of her two dead daughters. "I don't want them just in my dreams. I want to really see them again."

There have been a lot of people like Tina Padilla.

Denver's updated Vision Zero action plan cites crash data indicating between 20 percent and 25 percent of pedestrians killed in traffic in the last five years were experiencing homelessness. Many live along dangerous transportation corridors, officials wrote, which increases their exposure to traffic and its dangers.

The new plan identified four areas that need immediate safety improvements: downtown, East Colfax, the Broadway-Lincoln corridor, and South Federal Boulevard.

In April, a tiny group of protesters milled about with people -- some homeless, some not -- at a bus stop near one of those focus areas on Federal Boulevard. Drivers had hit and killed two pedestrians near there within a month this spring.

The organizer, Alejandra Castañeda, a mother who lives in northwest Denver -- who has done contract translation work for Denverite -- stood with a sign that read, "NO MORE DEATHS. WE DESERVE SAFE STREETS." Dozens of cars sped by every minute.

"I'm often sad, often angry, frustrated," Castañeda said as she shivered through a spring rain storm. "I feel like we need in Denver a movement of people coming together and saying, 'That's enough. We won't take this anymore.' And I don't know if it's possible. I'm feeling a little hopeless lately."

Safe street advocates might find hope, though, in survivors like Taylor Joachim.

In the first draft of her life, Joachim should be playing volleyball professionally right now. Instead, the University of Denver graduate is relearning how to use her body and mind after she survived a crash in April 2019.

She was nearly across University Boulevard -- a four-lane arterial street -- when a driver ran a red light and hit her at 35 mph.

"I don't even remember it," Joachim said. "Thank god that I don't."

She was treated for traumatic brain injuries; the force of the collision broke some of the blood vessels that connected her brain to her skull.

Her brain could no longer filter sounds -- a whisper sounded like a shout. Her eyeballs wouldn't dilate properly. She couldn't keep her balance. Her skin was super sensitive to temperature changes. She'd forget her thought mid-sentence.

Some of the symptoms have improved, but Joachim said life is now "extremely tiring and extremely exhausting."

"It's like I have to manually operate my brain," Joachim said.

She had to give up volleyball, too. But Joachim has found a new passion: street safety. She tells her story to anyone who will listen. And she's newly critical of those who have the power to make a difference.

"It's a policy choice to have unsafe streets," she said. "We could very easily have raised crosswalks on streets that would slow down traffic."

Joachim recently moved back home to her small hometown in Michigan, where she hopes to regularly attend City Council meetings and advocate for safer streets. She has pursued a new career in advertising after she graduated during the pandemic.

Her commencement was held virtually. So she found another way to mark the end of her old life and the start of the new one: She walked across University Boulevard.