The artist Cheyanne, played by Iliana Lucero Barron, dips and swipes a paintbrush against a canvas that the audience can only imagine but never see for themselves.

Cheyanne stares intently at the painting, her eyebrows pulled closer together. Stage left her boyfriend Rodrigo is aiding her father Frank, a former house painter ailed by dementia’s demons.

The stage lights flicker. Play director Phil Luna leans over from his seat in the audience:

“We are still working on the lights,” Luna said.

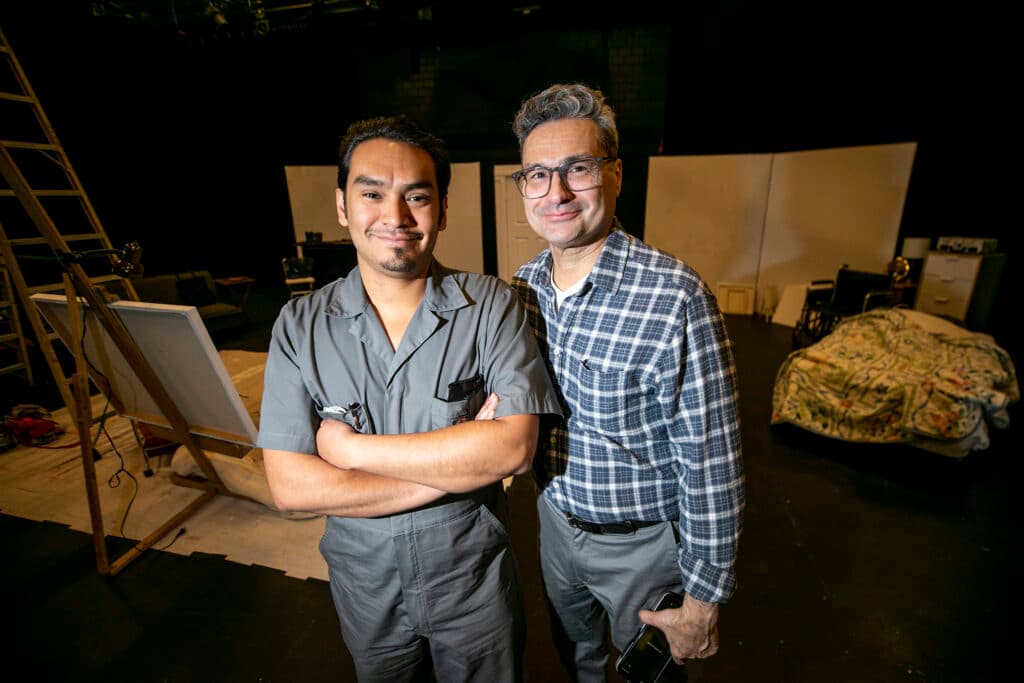

Cipriano Ortega, who plays Rodrigo, wrote the original iteration of “Cheyanne” years ago as an assignment at Metropolitan State University. Born and raised in Denver’s Northside by two professional artists, the show depicts the experience of brown artists learning to navigate a complex and nuanced art world.

The loss of a father’s memory, the pressures of an ambitious art dealer and the tensions of love and art draw on themes of gender, class, race and health that Ortega knew all too well growing up.

“I don’t think there’s any villain per se,” Ortega said. “I think all of them have their reasons for why they’re doing what they’re doing. And I think that’s life.”

The dramatic romance, set in a one bedroom apartment, premieres at The People’s Building in Aurora on Friday, April 26 and will run for two weekends. Tickets are $18-$38. The show is supported by Control Group Productions.

Ortega’s playwright debut was inspired by how his family navigated Denver’s art world.

Ortega wrote the fictional narrative around his own experiences raised by professional artists Sylvia Montero and Tony Ortega.

An artist, musician, actor and now playwright, Ortega has had to navigate his own intersectional identities as an Indigenous, Chicano, queer artist to fit the mold of a “successful” creative.

Ortega’s mother is of Apache descent with ancestors from Texas that never settled on a reservation. While applying for Indigenous grant money for a project years ago, Ortega was asked to provide official government recognition. Phone calls to Apache reservations looking for the “Montero” name in registers were to no avail.

“Even though I know for a fact I’m Indigenous, I don’t have the ‘papers,’ the U.S. government provided institutionalized representation of that,” Ortega said. “This show in particular I just wanted to show my modern interpretation of what it’s like to try and juggle all these things as brown people.”

Living in the Northside for the last 33 years, Ortega lives in the same home that he moved into when he was just two days old. The play draws on his Latino background, utilizing aspects like Spanglish dialogue and original blues inspired music, to help draw the audience into what a Northside artist’s home would have been like.

“Each character in this current iteration really is a representation of all the archetypes that a lot of people of color have to play into to be recognized and be a professional artist in the world,” Ortega said.

The role of Frank, played by Angelo Mendez, was introduced after Ortega’s grandfather passed away in 2020 of COVID and other medical complications. A loss that Ortega said is still “very challenging to deal with.”

“I didn't know that he was going to change it so much,” Luna said, recalling what the first iteration of the play was like. “The passing of his grandfather was such an influence that it changed the trajectory of this play.”

For Ortega, it’s true that life dictates the artist and what they are going to do. For Cheyanne and Rodrigo, the struggle to give birth to their creative processes is now amplified by the emotional labor required to care for a loved one. And for the artists, fictional or not, the pressures to sell their art looms large. Ortega uses the vignettes of these characters to communicate what he sees as the true antagonist.

“The main opposing enemy to all of this is capitalism,” Ortega said. “That’s what dictates what people will see in terms of... what is deemed as successful.”

The art dealer Lisa, played by Magally Luna, embodies the economic pressures that Cheyanne and Rodrigo face in light of their true creative expressions.

All of this is cast onto the play’s true fifth character, the canvas. Downstage and slightly off-centered, the canvas is silent. It carries the anxious paint strokes of struggling artists, hiding its face and begging one to imagine what this depiction of a Northside family might come to create.