You might recognize the Mosque of the El Jebel Shrine by the Islamic-influenced spires that stretch above its structure on Sherman Street, just a few blocks north of the Capitol.

But, for decades, it was the building's interior that was known throughout Denver.

The "mosque" was completed on Nov. 1, 1907, by local Shriners — the social club whose members wear fezes and are thought of today for their children's hospitals.

It changed hands over the years, then finally closed in 2012, leaving the memory of its ornate insides to languish and fade.

But fear not, historically minded reader, you may have a chance to step inside and see it for yourself.

The building has just undergone renovation, and it's reopening for the first time for a decade.

Non Plus Ultra, a company that throws events in historic spaces like this, have taken up residence in the shrine's ornate halls. They've activated it once so far, for a boxing match in April, and say they're now open for bookings.

"For us, it's ideal. It has so much character," Lindsay Probasco, the company's head of sales told us. "You bring event planners in and it's heaven, because they have to do minimal decor. They don't need pipe and drape. They don't really need to bring a lot."

Probasco said a "Harry Potter"-themed party, or maybe something like the "Bridgerton" ball they put on in 2022, would fit nicely in the arcane space.

The shrine was originally a place to get down.

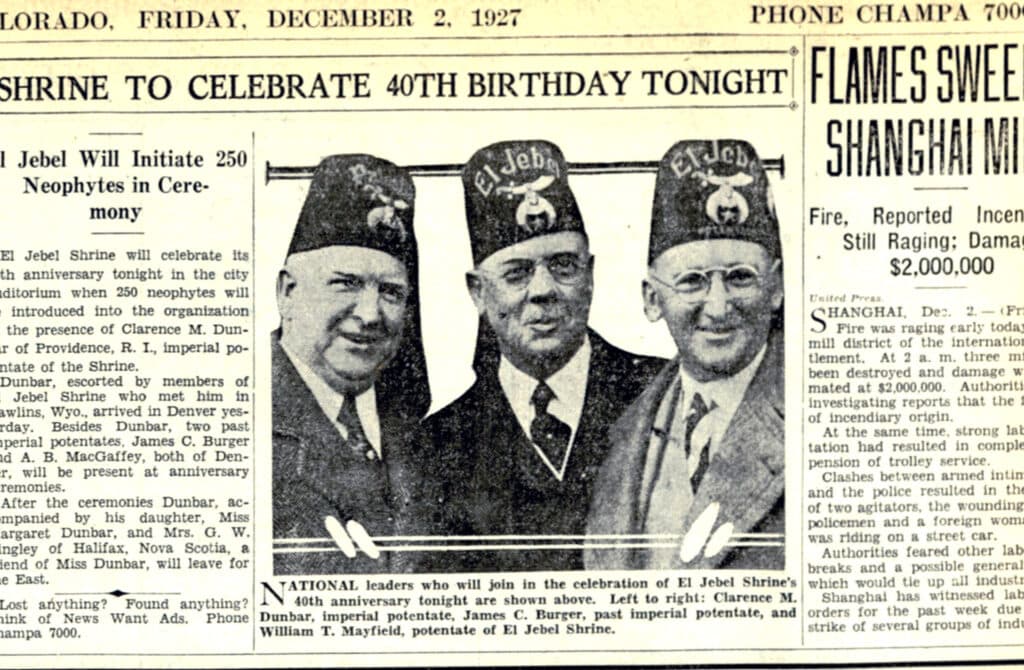

According to an application to list the structure in the National Register of Historic Places, Denver's Shriners first organized in 1887, meeting in an upper room in the city's fire station.

"The Denver order assumed the name 'El Jebel,' Arabic for 'The Mountain,' on the suggestion of charter member Mortimer J. Lawrence," it reads. "In 1902, a committee was appointed to investigate the feasibility of purchasing a site and building a Shrine mosque."

The Rocky Mountain News reported the building's cornerstone was ceremoniously placed on June 9, 1906, delayed a few weeks to ensure national Shriner leadership could attend. The organization put on a parade and a banquet to celebrate the occasion.

"It will be one of the finest fraternity structures in the country when finished," the report read.

The shrine was added to the National Historic Register in 1997. According to the application, the building cost $190,000 to construct, $15,000 of which went to buy the land.

News reports from the era tell of grand parties and celebrity visits there.

One Rocky Mountain News account from April 1912 describes "continuous vaudville on one floor," dancing, bazaars and "aviation fizzes" — apparently, a house drink — "on every side."

"Beautifully gowned women mingled with the members of the patrol, whose red and white fezes gave a touch of color to the scene," the story reads. "Although the affair was buy semi-formal, many stunning costumes were seen."

They apparently also frowned on some of "the new popular dances."

“Hang onto the rope and nix the Grizzly Bear, Turkey Trot or Texas Tommy, except by special permit," the Rocky reported seeing in the event's program.

This was part of Shriner culture back then, the National Historic Register application suggests.

"The Shriners built their mosques to facilitate 'masculine jollity.' One could argue that Shriners were just as interested in having a good time as they were in emanating good taste," it reads.

A fire sent the Shriners northward, but the wild architecture cemented their legacy on the block.

The authors of El Jebel's historic status application leaned heavily on its interior for their argument; usually, it's the exteriors that get all the attention.

It was designed by brothers Viggio and Harold Baerresen, described in the application as a huge shift from their usual work.

"The El Jebel mosque represents a major departure for the Baerresens. No models existed in Denver for the type of structure they envisioned. They employed a wide variety of stylistic types ranging well beyond anything found in Denver or generally accepted in other American cities," it reads. "Whether they traveled to the Middle East or arrived at their design through reviewing secondary sources, Baerresen Brothers set the standard for exotic revival and eclecticism in Denver."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

The application cites words from one Richard Brettell, who penned an analysis of Denver's early architecture and named the shrine "the Baerresen's greatest eclectic achievement."

Brettell also seemed wryly amused with its many styles, calling it a "marvelously tasteless temple," though maybe in a good way.

"The Baerresens attempted almost archaeological reconstructions of what they imagined to be

the great exotic styles of the past and present," he wrote. "Represented are Egyptian, Alhambra,

craftsman, Flemish, gothic, Japanese, French Salon, and Empire styles. Each room is

separate from the others, and each great style of the past stands in isolated splendor."

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

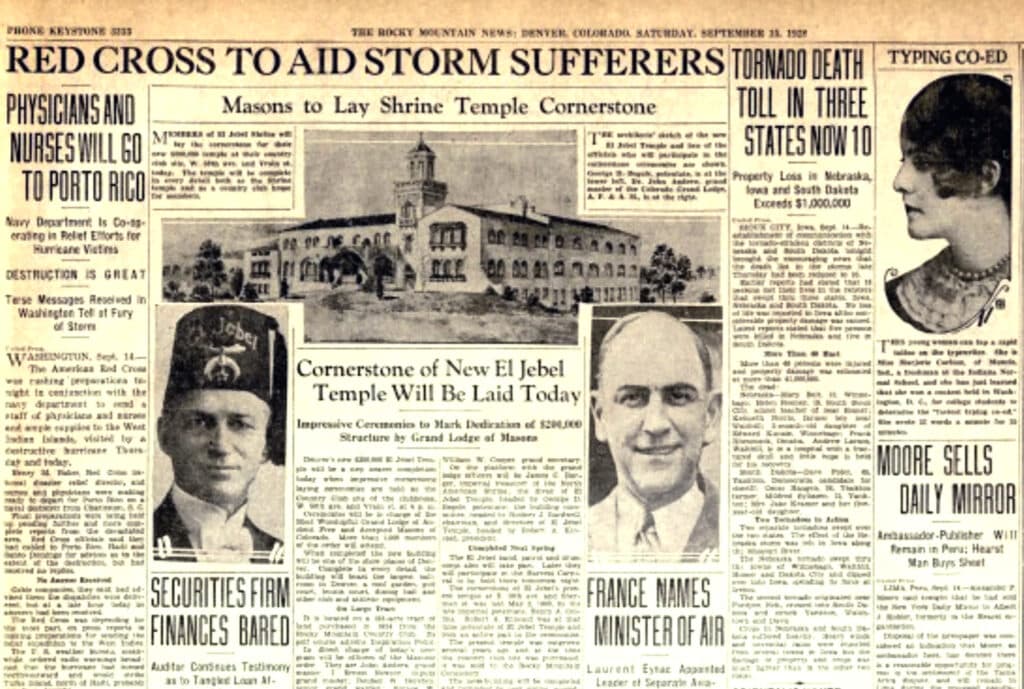

The historic application says the space served the Shriners well for almost 20 years before an opportunity to upgrade presented itself.

"A serious fire in March, 1924, proved fortuitous for the chapter," the document says. "El Jebel had outgrown its home and members were interested in building on a new site."

They'd sell the property "as is" to a group of Masons, their organizational cousins, for "a considerable cash payment."

The Shriners would take their burgeoning ranks to Inspiration Point, in Denver's northwest corner, where they built a new shrine at 50th Avenue and Vrain Street — then celebrate the laying of yet another cornerstone. That shrine, another odd bit of architecture in Denver, still stands, though it's now a condo building.

But those early Shriners seem to have valued the idea of building something beautiful for the future, no matter who might own it next. Above a doorway in one of the Sherman Street building's first-floor parlors, stained glass reads "the workers die, but the works live on."