Dispatchers once sent Denver Health paramedic James Boyer to a call near downtown — a routine occurrence for a first responder who has worked in the Denver area for 12 years.

The only problem? The caller didn’t know their address and was only able to tell a dispatcher they were located on a bridge and they could see REI.

“How many bridges can you stand on and see REI?” Boyer asked a class of paramedic trainees last week. “We found this person on the ninth bridge we checked.”

Every second counts in the world of emergency medicine. While paramedics have GPS in their vehicles, the devices don’t always reliably give first responders the information they need to respond and navigate to a hospital from anywhere in the city.

Paramedics can’t stop to orient their GPS while speeding down the street with sirens or afford to wait while a computer reroutes them at a road closure. And paramedics regularly need to find someone on a bridge, somewhere in the city — fast.

When it comes to Denver’s streets, they need to know it all.

While police have precincts, fire departments have set stations and bus drivers operate on regular routes, everything within Denver’s boundaries is territory for local paramedics.

That’s why, on top of medical training, paramedics in training at Denver Health also take a navigation class, followed by months of driver training in the field. Paramedics must also pass a written streets test and a driving exam before they can get started on the job.

Boyer, who can get around the city blindfolded if he needed to, developed the navigation class a few years ago when he realized some trainees struggled to orient themselves in the city. A few times a year, he sets up in a classroom and passes out a street guide to trainees, which includes the name and block number of nearly every Denver street. Then, he gets to work teaching trainees how to memorize it.

Last week, Denverite joined Boyer’s class to find out what everyday people could learn from how paramedics navigate the city. Most people keep mental maps of their community — but what happens when you pair that with a deep understanding of the underlying system?

The answer involves a new understanding of Denver’s street signs, its geography and the city’s history. Plus: the ability to get nearly anywhere without using a GPS.

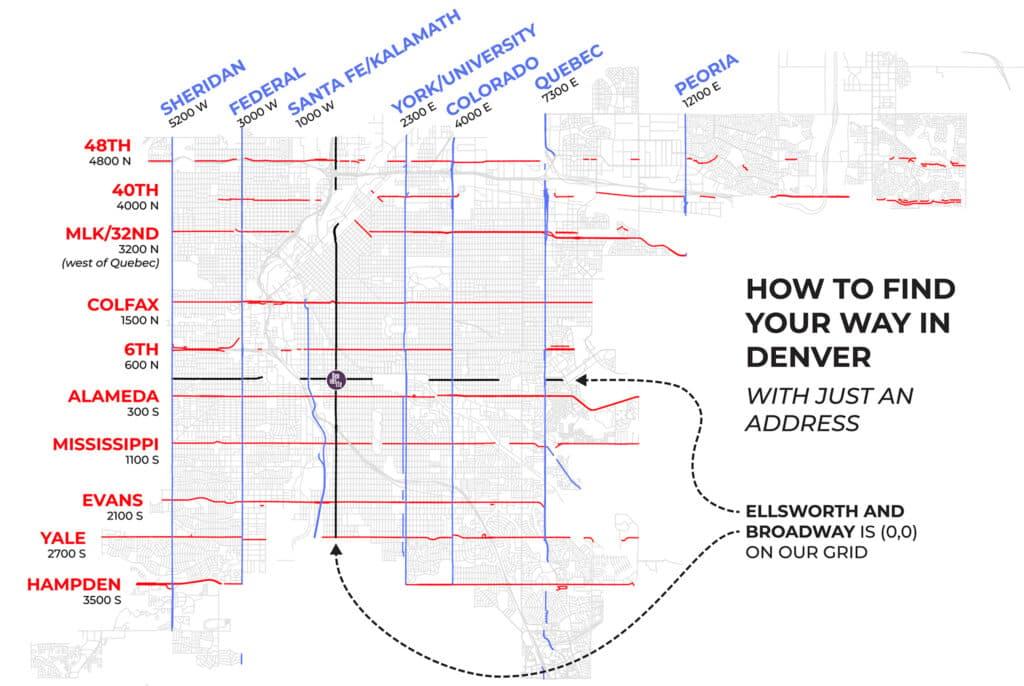

The first thing to understand is that Denver is oriented on a grid system (with the exception of downtown).

But it’s the center of the grid, Broadway and Ellsworth Avenue, that unlocks the key to navigating most of the city.

North of Ellsworth Avenue is the easiest because most of the streets are numbered. Take 14th Avenue for example — that’s 14 blocks north of Ellsworth Avenue. That means if the numbers start increasing, you’re headed north; if they’re decreasing, you’re headed south.

All the other streets are a memory game, but there are many patterns.

Most of Denver’s non-numerical streets are alphabetical, moving further along in the alphabet the further they are from that Broadway and Ellsworth intersection, before hitting Z and starting over again. Some streets mirror the ABCs, while others follow an AABBCC pattern.

There are other patterns, too. The streets immediately West of Broadway move alphabetically and start with names taken from indigenous and Chicano cultures. East of Broadway — non-alphabetically — begins a crowded category of streets Boyer calls “old dead white people.”

The AABBCC pattern picks up with tree names once you pass Colorado moving east, later turning into international city names. South of Ellsworth Avenue the streets start their ABCs with U.S. state names before moving to University names (coincidentally right by University of Denver).

“From that base knowledge of just memorizing the streets and numbers, it grows from that to then being able to build a mental map,” Boyer said.

Boyer suggests Denverites learn a few key rules and throughways to travel GPS-free and get a new view of the city.

To start: all avenues, places and drives run east to west, while all streets, courts and ways run north to south. Of course, the exception is downtown, which is oriented at a 45-degree angle aligned with the South Platte River.

Another fun fact: buildings on the south or east side of the street have even numbers, and houses on the north or west side of the street have odd numbers.

Paramedics need to learn the block numbers and names of every street on the grid system. For everyone else, here are some key roads Boyer recommends learning, along with their block numbers.

Knowing the block numbers unlocks an entirely new meaning to Denver’s street signs. The numbers tell travelers how many blocks north, south, east or west they are from the center of the grid at Broadway and Ellsworth Avenue.

To become a true Denver streets expert, Boyer says residents should know their way around the city’s trickier streets.

“I had a question years ago from a candidate, they said, ‘Which areas should I focus on?’” Boyer recalled. “I was like, ‘Well, you gotta learn the whole city, so figure it out.’ It was a really bad answer. The better answer is anywhere where the grid system is just not good, or more so if there's a big obstruction, so a diagonal, or the highway or by the river.”

The city has dozens of streets that run at a diagonal, including all of downtown, which interrupts the grid system with its own grid at an angle. Then there are the highways that divide the west side of the city from the east side, and the topsy-turvy cul-de-sacs out in Green Valley Ranch.

Boyer recommends Welton Street street as a road to orient oneself in downtown. He says it’s helpful for paramedics because it provides a number of easy entrance and exit points when rushing to and from calls at the city’s core.

Boyer knows most people won’t memorize every Denver street. But he thinks knowing your neighborhood is part of what it means to live in a community.

After class, Boyer took me on a tour of the city in one of Denver Health’s cars, pointing out key thoroughfares and showing me his favorite ways to get around the city.

He took me to some tricky spots to navigate like the northern edges of downtown, and to some roads most people don’t know exist — like Old West Colfax Avenue, a nubby road that runs by Meow Wolf underneath the part of Colfax Avenue that connects the west side to the rest of the city (there’s also Colfax A and Colfax B, if you know where to find them).

Along the way, Boyer pointed out tidbits of Denver history tied to Denver’s streets, much of which he learned from Phil Goodstein, a historian who wrote a book on Denver's streets and who lectured to Boyer's class. There’s the history of Five Points, which is named for four roads that connect and is home to a long history of Black culture in Denver. There’s Colfax Avenue’s car-fuelled origin story, which is quickly converging with a pedestrian- and public transit-friendly future.

Boyer likes knowing the street names and where they come from — the answer often traces back to the whims of 1800-era developers. He likes knowing why downtown orients at a 45-degree angle, a configuration connected to gold panners working along the South Platte River. And he likes knowing things like how Denver initially got its streets organized thanks in part to utility companies that needed to bill customers in an orderly manner.

All that history is right there, lying beneath Denver’s street signs.

“I think if you are a part of a community, it's a good way to just raise your awareness generally about where you are, or where you work, or where you play or where you live,” Boyer said about learning the streets.

Regardless of how many streets residents have memorized, Boyer had one key piece of navigational advice for newcomers and longtime Denverites alike: “Spend time investigating your community.”