Does giving direct cash payments to people experiencing homelessness help alleviate poverty?

A one-year study following around 800 participants in Denver, one of the largest studies of its kind, says yes.

The Denver Basic Income Project is reporting “significant improvements in housing outcomes” among its participants, according to results released by researchers from University of Denver on Tuesday.

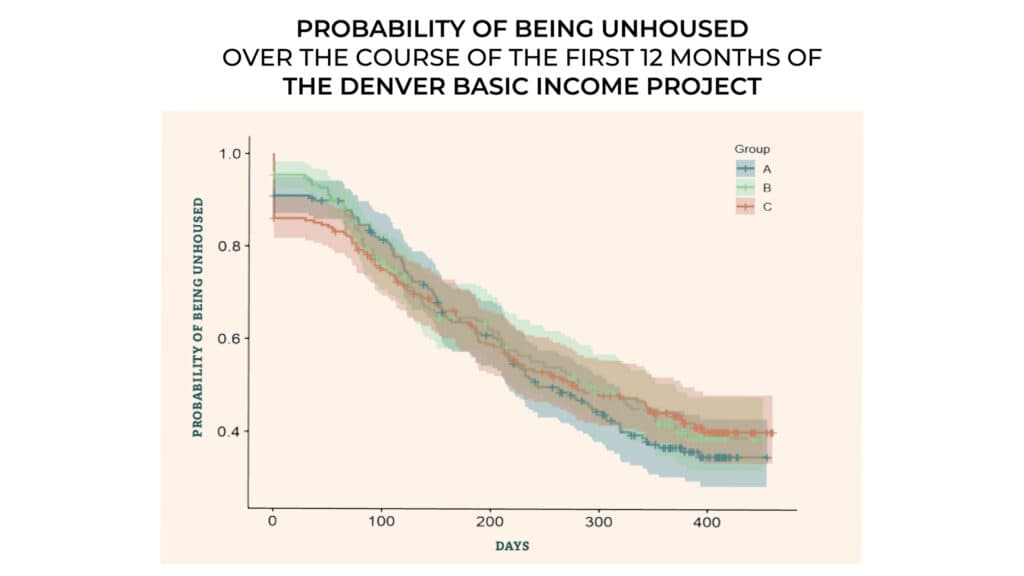

The study found that about 45 percent of original participants, all of whom were unhoused at the start, were living in their own house or apartment one year into the program.

Researchers also found that direct cash payments can lead to cost savings for public dollars, with participants reducing their use of public services and visits to places like emergency rooms and shelters.

What is basic income?

Universal basic income — cash payments to people living in poverty, no strings attached — has taken off as an idea among some philanthropists and politicians in recent years.

Denver’s nearly $10 million pilot project began in 2021, funded with a mix of private donations and $4 million from the city. DU’s study is one of the largest looking into the efficacy of the idea.

“Our current social safety net is really built on a more paternalistic type of set of rules and expectations for people,” said Mark Donovan, founder and executive director of Denver Basic Income Project. “When we approach people and say to them, ‘We believe in you. We trust you,’ at first they don't believe us because they're so used to being let down. But when we actually start delivering the unconditional cash, even in small amounts … we see this wall of distrust lowered quickly, and we create a platform for change.”

How the Denver Basic Income Project worked

Program leaders worked with local nonprofits to connect with eligible participants, who must have been unhoused and without severe, unaddressed substance abuse or mental health issues.

Participants were also chosen to reflect the racial and gender demographics of people experiencing homelessness, where a number of minority groups are overrepresented.

They were then randomly split into three groups.

Group A received $1,000 per month. Group B received $6,500 upfront and $500 per monthly moving forward. Group C, the control group, received $50 monthly.

Researchers reported that participants largely spent money on things like transportation, hygiene, groceries, housing, health care and debt.

“We know that unhoused people use resources in the same way housed people do - to cover basic needs — and we’ve seen this program bring relief, peace of mind, and stronger paths to stability to the participants we’ve enrolled,” said Cathy Alderman, chief communications and public policy officer with Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, in a statement Tuesday.

So, what did we learn?

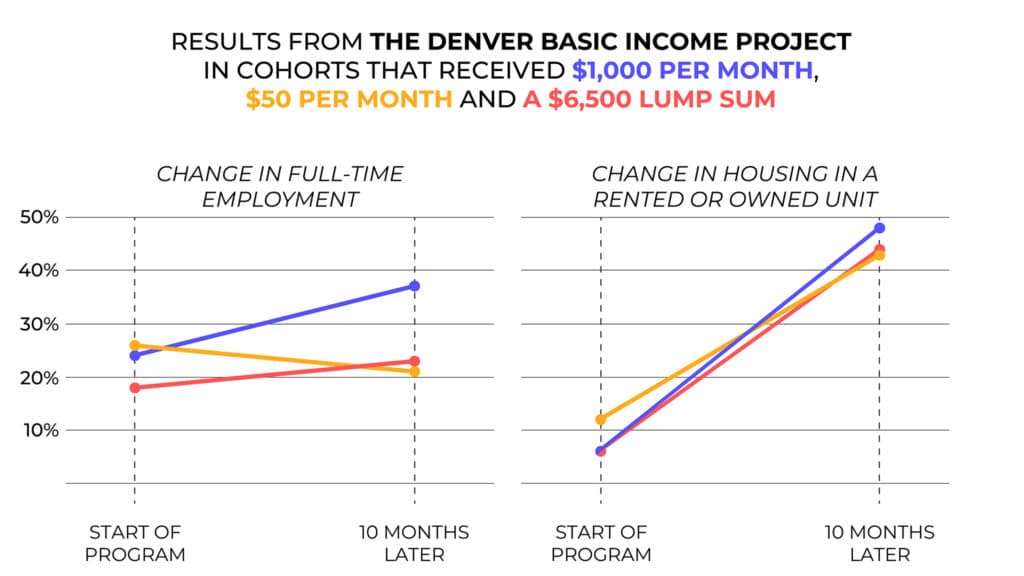

The study found that the percentage of participants in stable housing approximately doubled within 10 months in all three groups, a statistically significant result according to researchers.

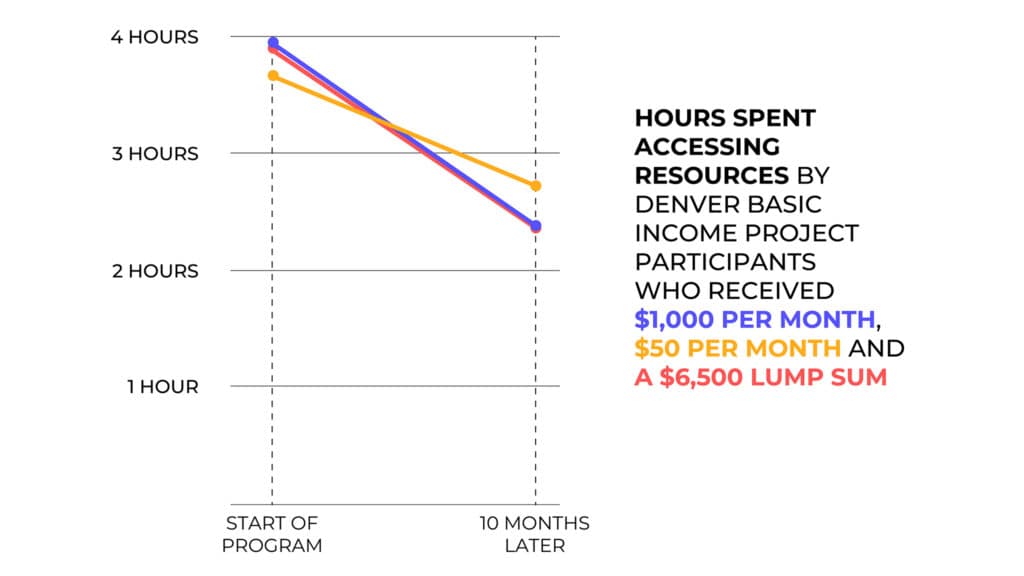

All three groups also saw reductions in accessing public services, another statistically significant result.

Participants also reported an increase in overall financial well-being and an increase in full-time employment.

Researchers also looked at a number of other factors including sleep quality, food insecurity, anxiety, parenting stress, transportation resources and more, with full qualitative and quantitative results released online.

Overall, the study found that the probability of experiencing homelessness decreased for all through groups while receiving cash payments for 12 months.

“The most impact it had on me was a promising future, versus before, it wasn’t looking so good," said one anonymous participant quoted in the report. “It’s a light at the end of the tunnel, and before, I was kinda lost. It just really gave me some hope.”

What’s next for Denver’s universal basic income experiment?

The program was extended for a second year, thanks in part to a $2 million infusion from the city.

Donovan said he hopes to see the program sustain funding in Denver for a third year, while also replicating the study in other cities to test the ability to scale universal basic income.

While other cities have also experimented with basic income pilots, Denver’s program is one of the biggest studies on the concept so far.

Sustained funding remains a challenge. The program needs another $2 million to fill out its second year, while also fundraising $8 million with the hope of running for a third year.

Ultimately, Donovan wants to see universal basic income incorporated into public policy.

“The first year we see is creating a sense of stability, but we're already seeing the housing incomes continue to improve month to month, and we believe that the second year, and even beyond, can be even more profoundly transformational,” Donovan said. “We know what happens when benefits are eliminated, and we know about the benefits cliff, but we don't know what it looks like when you sustain an income floor.”