Mayor Mike Johnston made a promise after Donald Trump won November’s election: Denver would still be a welcoming place for immigrants.

“We’re not going to sell out those values to anyone,” the first-term mayor told Denverite. “We’re not going to be bullied into changing them.”

Those values were born from 30 years of city and state debate. Since the late 1990s, Denver’s mayors have invited immigrants to participate in civic life and city services, even during national immigration crackdowns.

Now, with President Trump’s sweeping deportation plans, and Denver in the rhetorical crosshairs of conservative politicians, the city’s welcoming attitude is under threat again.

With the new federal administration taking power, Denverite spoke to city leaders, state lawmakers, immigrants and advocates on multiple sides of the issue. Our question: How did Denver and Colorado become some of the nation’s most supportive places for immigrants?

And what happens next?

In the 1990s, Denver’s mayor defied the national political consensus on immigration.

Both political parties were calling for stronger border laws. Many Mexicans were moving north because of the effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement. And labor unions were pushing the Democratic Party to get tougher on undocumented workers.

“We cannot tolerate illegal immigration, and we must stop it,” the Democratic Party declared in its 1996 platform. That same year, President Bill Clinton signed bipartisan legislation making life without documentation harder in the U.S.

“Democrats at that time were against illegal immigration,” said John Fabbricatore, who worked in immigration enforcement since 1998, before retiring as the Field Office Director for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Denver.

But in Denver, Mayor Wellington Webb stood against his party.

“We welcome all to share Denver’s warm hospitality,” Webb, a Democrat, declared in a 1998 executive order.

Webb rejected “unlawful discrimination in any form” and promised equal access to services to all residents — defying a bipartisan federal law that denied public benefits to some immigrants. He urged business leaders, hospitals, schools and neighboring municipalities to serve immigrants.

Many of those institutions followed Webb’s charge.

“You want to welcome people to your city,” Webb said in a recent interview. “You want to welcome all people to your city.”

Webb’s upbringing in Denver inspired his welcoming attitude. In a recent interview, he recalled his time at Manual High School in the late 1950s. A third of the students were Black, a third were Latino and the school also included Japanese-American kids whose families had been imprisoned at the Amache internment camp.

“We learned to get along with everybody,” Webb said. “We had a sense of camaraderie among ethnic groups that I thought made Denver stronger.”

Colorado Republicans soon pushed for even stricter policies.

In the 1990s, Colorado politician Tom Tancredo emerged as a leader of anti-immigration Republicans. He took that message statewide with Ted Harvey, then a young Republican activist.

Illegal immigration, they argued, unfairly burdened taxpayers who were footing the bill for immigrants’ medical care and education. Coloradans weren’t always receptive to the message.

“You’re called racist,” Harvey said. “You’re called evil if you don’t want to have open borders and allow people to break our sovereign borders.”

Tancredo won election to Congress in 1999, representing the southern and western metro area. He would later run for president, attacking the “cult of multiculturalism” and calling for a return to “Western civilization.”

In the early 2000s, immigration hardliners gained influence after the 9/11 attacks. The hijackers had all entered the country legally, but politicians began associating foreigners – and especially undocumented immigrants — with terrorism.

The Bush administration moved immigration enforcement under the Department of Homeland Security in 2003. Enforcement teams tracked down people who had refused to leave the U.S. after a judge ordered them to, Fabbricatore said.

In Colorado, a Republican-led state government was rolling back benefits for undocumented immigrants. In 1999, state lawmakers banned undocumented drivers from getting driver’s licenses, and in 2004 they blocked those with existing licenses from renewing them.

Without a license, an undocumented immigrant who was pulled over could end up referred to immigration enforcement for potential deportation.

Advocates argued that taking away driver’s licenses put the public in danger. Undocumented people would drive to work either way – but now, they wouldn’t take driving tests.

It would be a decade before the state dropped the ban.

Colorado’s immigrant rights movement came to life in the 2000s.

Xenophobic rhetoric, the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and rising deportations sparked a renewed immigrant rights movement.

“I lived with other friends, and we were really scared and worried about the anti-immigrant environment,” recalled Homero Ocon, who had lived in Colorado without documents for years since the late ‘90s.

Ocon called the television network Univision with his concerns. The channel referred him to Rights for All People, one of a few immigrant advocacy groups in Colorado at the time. He joined the growing movement.

One of the biggest moments came in 2006, in response to a federal proposal to make illegal immigration a felony.

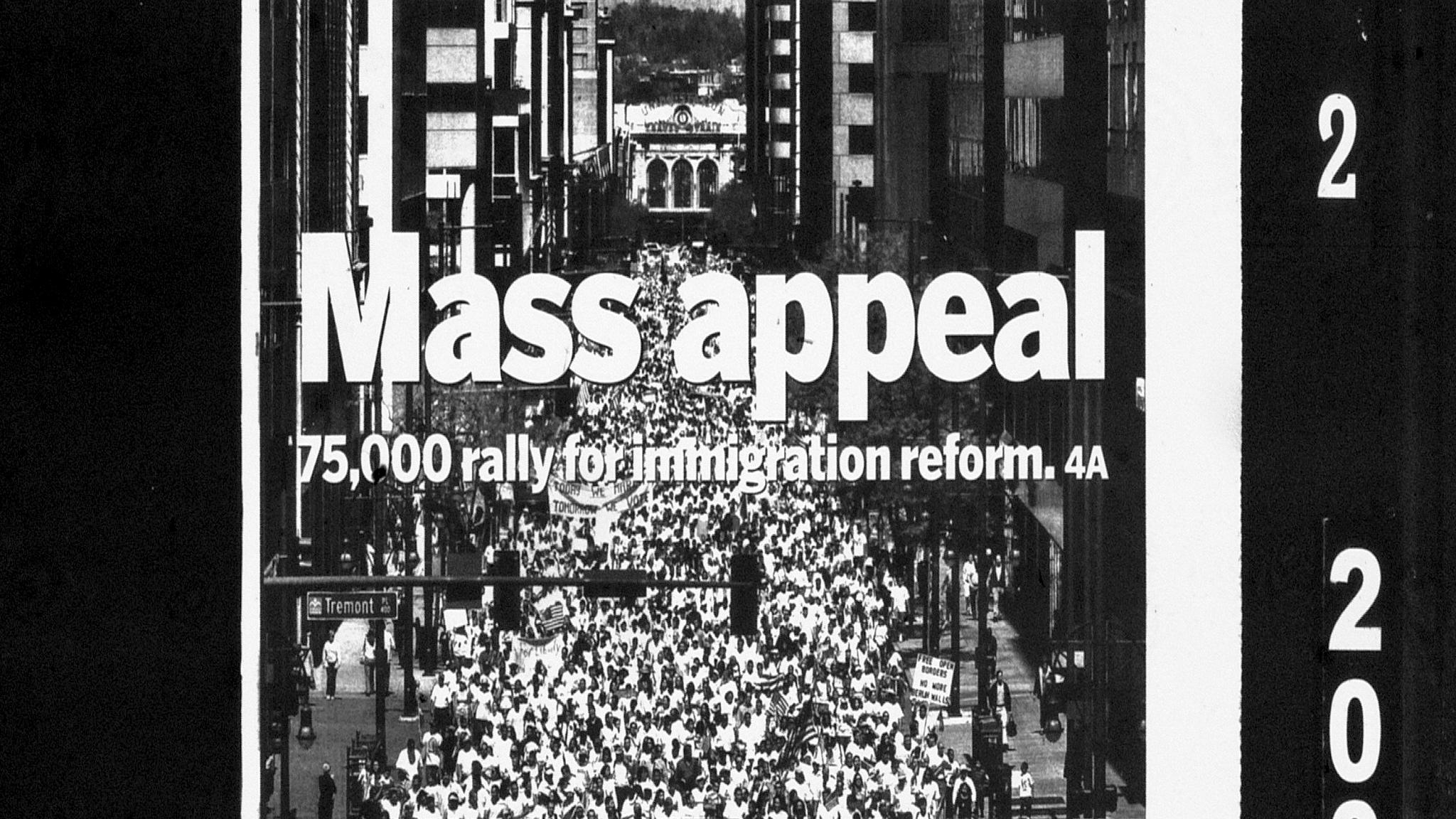

In response, millions of people nationwide – including many undocumented immigrants – flooded the streets for mass demonstrations. They walked out of workplaces and schools in the Day Without an Immigrant protests.

Immigration attorney Cristina Uribe Reyes was an undocumented student at George Washington High School at the time. When she arrived downtown, she saw tens of thousands of people – documented and undocumented – fighting for her.

Denver police estimated 75,000 people marched to the state Capitol.

“This is where I belong,” she thought.

The controversial bill ultimately failed in Congress. But after the protests, ICE ramped up raids at workplaces. At a meatpacking plan in Postville, Iowa, roughly 900 ICE agents detained hundreds of immigrants, and nearly 300 were deported. ICE also carried out raids in Loveland and Greeley in the following months.

Some Spanish-language media blamed the raids on the protests, Ocon recalls. Many immigrants left the movement.

Soon after the demonstrations, Colorado passed even stricter immigration laws.

Throughout 2006, Tancredo and other right-wing organizers gathered support for Defend Colorado Now, a ballot measure to block undocumented immigrants from a range of public services. More than 55,000 people signed petitions, the organizers said.

But that June, the Colorado Supreme Court squashed the effort, saying the proposal was too broad. In response, Republican Gov. Bill Owens called lawmakers to the statehouse for a special legislative session on immigration.

Owens didn’t believe in providing government services to people who came to the United States illegally. Doing so, he argued, discouraged legal immigration.

“That was a consensus at the time,” he said.

It was an election year, and Democrats didn’t want immigration on the ballot, Owens recalled. They feared it would split the party and cost them races. Instead, many statehouse Democrats joined Republicans in passing some of the nation’s strictest immigration laws.

“They stood together on the steps of the Capitol and declared that Colorado had the toughest immigrant laws in the country,” recalled longtime immigrant rights activist Jennifer Piper, with the American Friends Service Committee.

One of those policies became known as the “show me your papers” law. The law, SB-90, forced police to report to ICE when suspected undocumented immigrants were arrested.

Harvey, then a Republican state lawmaker, was a sponsor of SB-90. He thinks now that the state’s Democratic Party benefited politically from supporting the new laws at the time.

“I would argue, the reason why the Democrats have control of the state now is because the governor negotiated with them at the last minute on the illegal immigration package,” he said.

American Friends Service Committee organizer Jennifer Piper speaks at a press conference inside the Colorado State Capitol decrying President Trump's new immigration policies. Jan. 22, 2025. Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

State Sen. Julie Gonzales speaks speaks at a press conference inside the Colorado State Capitol decrying President Trump's new immigration policies. Jan. 22, 2025. Kevin J. Beaty/Denverite

The result of SB-90, state Sen. Julie Gonzales said: Immigrants grew more afraid to report crime. She witnessed it as a paralegal for the Meyer Law Office, where she worked for years before becoming a state senator.

The change also resulted in some legal immigrants getting stuck in jail for harrowing hours.

“I’m not a criminal; I’ve never done anything wrong. But this situation made me feel like a criminal for being who I am,” one man told The Colorado Statesman in 2012.

Colorado’s immigrant rights movement grew under President Barack Obama.

Throughout the 2000s, President George W. Bush’s administration pressured local governments to help with immigration enforcement. Local police collected fingerprints and other data to share with federal forces.

Obama’s election didn’t seem to slow the immigration enforcement machine.

“Bush piloted it,” Gonzales said. “Obama perfected it. And Trump put it on steroids.”

In fact, Obama deported more people than Bush did — and than Trump later would. In Aurora, the private GEO Group expanded its detention center from 400 beds to 1,500 after Obama took office.

Undocumented youth nicknamed Obama the “Deporter in Chief.”

At the same time, immigrant rights advocates were rebuilding the momentum that had previously brought people to the streets in 2006.

Advocates trained more than 600 people to gather ballot-measure petitions. As many as 6,000 volunteers were organizing statewide, recalled Piper. They strengthened union ties, and the labor movement embraced undocumented immigrants. Others tried to convince local cops to stop helping ICE.

“It’s not the same as mass mobilization onto the street, but those were deeply-sustained, deep-in-community moments where there was a really large base of folks who were feeding something themselves, who were not just participants, but actors in their own liberation,” Piper said.

When Obama came up for reelection in 2012, two undocumented students occupied his Denver campaign office for five days, holding a hunger strike to demand immigration reform, Gonzales recalled. The action inspired protests and candlelight vigils.

“We’re not doing this for us,” Veronica Gomez told the Associated Press.“We’re doing this for the community as a whole.”

Days after the strike, Obama created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, a legal protection for young undocumented immigrants.

Still, workplace raids and arrests continued.

In Colorado, reformers’ efforts began to get results in the 2010s.

Democrats took full control of state government for 2013 and 2014. Lawmakers soon reversed tough-on-immigration policies — including the driver’s license ban. A bipartisan law in 2013 once again allowed undocumented immigrants to drive legally — becoming one of only a few states to do so at the time.

“Thousands of people were not deported thanks to that,” said Ocon, who worked on the effort.

In the same year, then-governor John Hickenlooper signed bills repealing the “show me your papers” law and granting in-state tuition to undocumented students.

Law enforcement was shifting, too. In 2014, the County Sheriffs of Colorado advised that local departments stop honoring federal immigration holds.

“Colorado sheriffs now agree that they have no legal authority to deprive persons of liberty, even for a few days, simply because ICE suspects an immigration violation," Mark Silverstein, then the legal director for the ACLU of Colorado, told Reuters at the time.

Then came Trump.

When Trump won the presidency in 2016 with virulent rhetoric about “criminal aliens,” Denver moved to protect them.

In 2017, nonprofits and volunteers mobilized as the Colorado Rapid Response Network, documenting immigration raids and other ICE actions.

Councilmembers Robin Kniech and Paul López met with immigrant rights activists and Mayor Michael Hancock, exploring how the city could resist ICE efforts within the bounds of federal law.

Denver reduced sentencing requirements to prevent low-level criminal convictions from triggering deportations. The city passed new hate-crime legislation and, in 2018, started spending $750,000 a year on legal defense for undocumented immigrants.

Meanwhile, Denver banned local law enforcement from using public resources to work with ICE in most circumstances — formalizing a longstanding practice. Law enforcement could no longer apply for grants that required sharing information with ICE. Interactions with feds would have to be reported to the City Attorney’s Office.

“We do not work with ICE,” former police chief Robert White declared.

City employees — starting with law enforcement — were trained on this, and violators could be disciplined, or even fired.

In 2022, Hancock signed an executive order creating a language-access program, providing interpreters for criminal investigations and all other city services. Cops would no longer recruit children to serve as de facto interpreters.

Conservative media blasted Denver as a “sanctuary city” for protecting undocumented immigrants. Many local policymakers rejected the term. After all, Denver could not stop federal authorities from detaining and deporting people.

“There is no such thing as a sanctuary city,” Kniech said. “It’s just a bizarre term. It’s a political weapon. There’s no legal definition. It doesn’t exist. Every city is bound to comply with federal law.”

Hancock himself denied Denver was a “sanctuary city,” frustrating some immigrant rights activists.

In response to their complaints, the mayor softened his stance.

“If being a sanctuary city means that we value taking care of one another, and welcoming refugees and immigrants, then I welcome the title,” Hancock said.

The City Attorney’s Office continued to deny Denver was legally a “sanctuary city” in any way.

Still, Denver did offer more protections than other communities.

The state soon followed Denver’s lead.

After Democrats retook full control of state government in the 2018 midterm elections, they passed similar protections for undocumented immigrants — with many of the changes led by Denver lawmakers.

New state laws banned local sheriffs from arresting or holding people solely on immigration detainers. Immigration arrests were banned around courts.

The state also removed more barriers for undocumented people to get licenses and apply for benefits.

Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez — now a Denver City Council member — helped pass those changes as a state representative. She and others said that undocumented people needed help during the pandemic.

“We are probably the most diverse group of legislators in both the House and the Senate and I think we see this as a real opportunity to dial back some of the things that did happen in years past,” she told CPR News at the time. “We know that immigrants, undocumented or not, are some of the main contributors to our economy.”

Critics argued that more benefits would attract more undocumented immigrants. Fabbricatore said it became harder for ICE to work with local police to make immigration arrests of suspected drug dealers and gang members.

“As sanctuary laws grew stricter, that became harder to do, because there isn't a good mechanism to share that intelligence,” Fabbricatore said.

From 2022 to 2024, Denver saw a surge in immigration.

In December 2022, Texas bused roughly 100 new immigrants to Denver, part of what critics described as “a cruel political stunt” to send undocumented people to sanctuary cities. Denver mostly welcomed them. Over the next two years, the state sent tens of thousands more.

Their arrival became an immediate crisis — and opportunity — for Mayor Mike Johnston, who took office in the summer of 2023. His message: This was “solvable.”

“All our problems are solvable,” he often says. “And we are the ones to solve them.”

The new mayor embraced immigrants, as did thousands of residents who housed, clothed and fed newcomers.

“It says almost countless times in our texts that we are commanded to, obligated to, called to love the stranger,” said Rabbi Emily Hyatt of Temple Emanuel, during a massive clothing drive.

Denver spent nearly $90 million sheltering newcomers and connecting them with resources, according to the mayor’s spokesperson Jon Ewing. Johnston slashed the city budget to pay the expense. The Biden administration, meanwhile, carried out record numbers of deportations, quietly exceeding those of Trump’s first term

The city begged for more federal help, growing frustrated with the Biden administration and congressional gridlock. The city did receive millions from the state, and tens of millions from federal sources.

But Johnston wanted more, advocating for faster access to work permits and federal immigration reform – a bipartisan measure killed in Congress after Trump opposed it.

As the election approached, Denver’s crisis became the focus of a national media frenzy. Countless reports centered on the presence of the Venezuelan prison gang Tren de Aragua. At a campaign rally, Trump pledged to deport “migrant criminals from the dungeons of the third world,” starting in Aurora.

Now that Trump is in office, Johnston has big decisions to make.

The mayor, and the city of Denver, have become a punching bag for Republicans nationally. Trump’s immigration czar, Tom Homan, threatened to jail Johnston if he resisted federal immigration authorities — after Johnston suggested thousands of “Highland moms” might protect immigrants.

This month, a congressional committee invited Johnston to testify about “sanctuary cities,” naming Denver as one four “abject failures” at enforcing immigration law.

At the same time, Johnston has tried to balance his message between support for immigrants and enforcing the law. He says Denver police will work with ICE in the case of violent crimes. Aurora has shared a similar message.

Right now, the Trump administration is preparing large-scale immigration arrests in the Denver area, even building a detention center at Buckley Space Force Base.

Will Denver be forced to respond to shock-and-awe raids on school kids, hospital patients and churchgoers? Or will Trump’s actions be quieter and more targeted?

Fabbricatore argues it will be the latter.

“ICE isn't going out there arresting 90-year-old people or some guys working in the back of a kitchen, unless that person is a Tren de Aragua member or another gang member or who has committed another crime,” he said. “So initially you're going to see them going after people who have convictions or have criminal charges, national security cases.”

One of the first local immigration actions came on the first weekend of Trump’s new term.

The Drug Enforcement Administration raided a warehouse party in Adams County, detaining 41 undocumented immigrants and eight others— some allegedly tied to Tren de Aragua. The investigation had been in the works for months before Biden left office.

ICE began publicizing the arrests, posting on Elon Musk’s X to thank the Denver Police Department for its help. In turn, Democratic Gov. Jared Polis thanked federal law enforcement for keeping guns and drugs out of the community — continuing a trend of at times praising Trump’s administration.

Immigrant advocates worry Colorado cities will bow to Trump.

The state’s laws were passed to defend Colorado communities “against the excesses of the Trump administration, against racist and xenophobic enforcement paradigm,’ said immigration attorney Hans Meyer, a leader in the immigrant rights movement.

Meyer is grateful Johnston has voiced his support for local immigration laws. But the attorney worries about collaboration between the city and the Trump administration and whether Denver is buckling under the federal government’s pressure.

“We in Colorado are in a very unique but important place where we have built-in protections that we now need to stand behind,” Meyer said. “We've talked the talk, and now it's time to walk the walk.”