As Denverites hunt for Black Friday sales, they might get jealous looking back into history – when you could buy alligator leather slippers for 85 cents, lace curtains for $2.50 and a boy’s suit for $1.25.

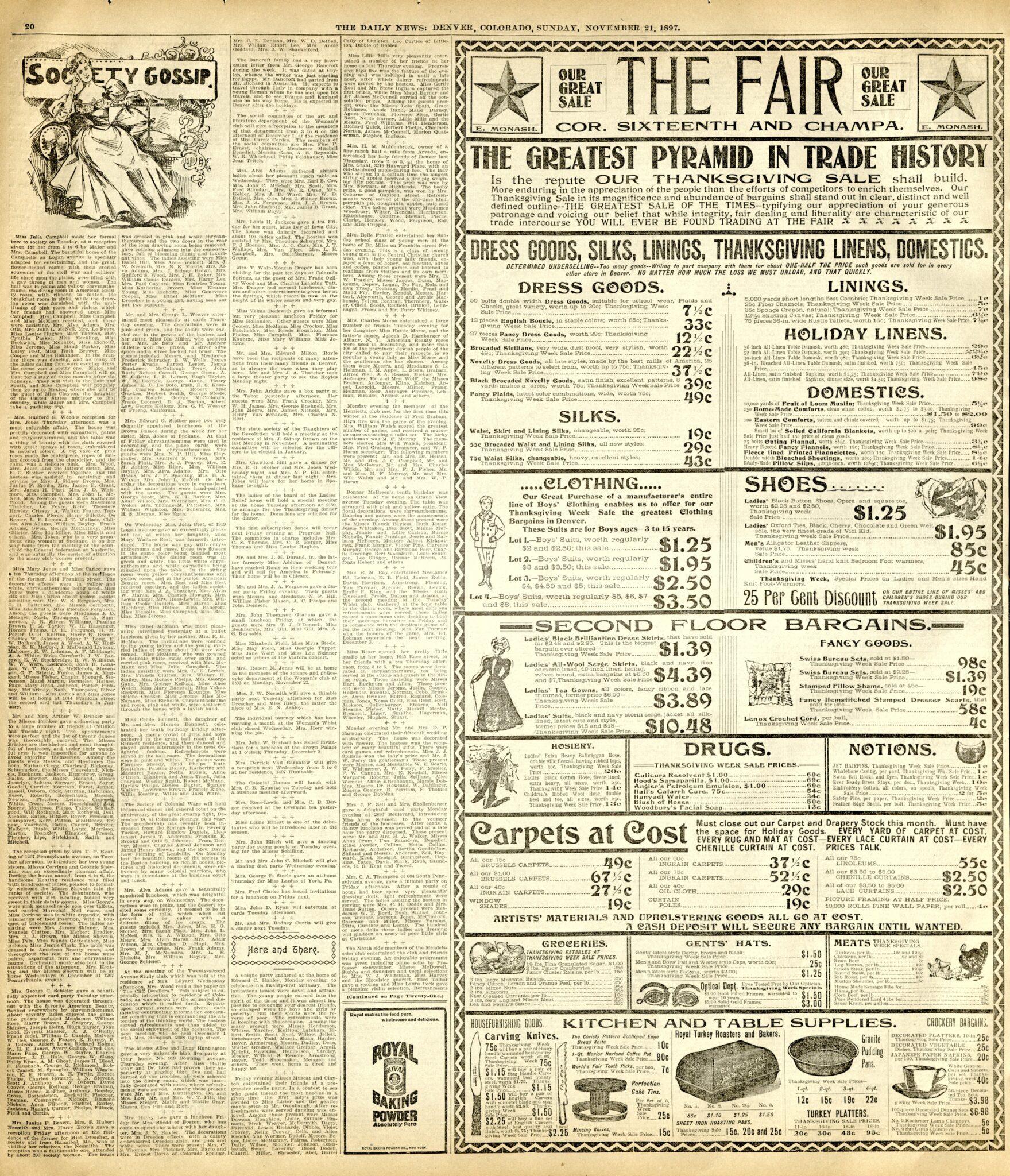

Admittedly, these were 1897 prices at The Fair, a store at 16th and Champa streets, during what was advertised in a full-page ad in the Rocky Mountain News as “the greatest sale of the times.”

The Fair sold all sorts of goods: linens, silks and flannels for pennies, along with ladies' opera shoes for $1.25, hose for 14 cents, and medications for 69 cents or less.

But there’s a catch: Many of those prices weren’t so affordable for the Denverites of the day.

Inflation, as always, is a pain.

First, a little context: In 1897, the average American earned $2.44 a day, or about $900 a year, according to federal statistics.

Inflation between 1897 and today was roughly 3,800 percent. In other words, one dollar in 1897 was the equivalent of about $38 today, according to federal estimates.

So, while these prices would be great if you had the income of today, they actually weren’t so affordable for the Denverites of the late 19th Century.

A turkey, on sale, once cost 10 cents a pound. These days, the cheapest price King Soopers advertised for a turkey on sale costs ten times that amount: 99 cents a pound.

But when you do the inflation math, modern-day Denver comes out ahead. Our predecessors were paying the equivalent of nearly $4 a pound.

You could buy 19 pounds of sugar for $1, while the same amount at a store in 2025 would cost $16.71. But with the rate of inflation, we’re once again doing better today.

Three pounds of cranberries would cost a quarter; today, the same amount would cost around $6. (Still winning in 2025.)

A caveat: The economy, our lives and the way we consume stuff have changed a lot in more than a century, so these kinds of comparisons aren’t very direct.

But, overall, people in olden times spent a lot more of their money on food, even if the prices look much lower.

One survey found in 1903 that families in the Western states spent about 35 percent of their income on food. By 2019, Americans were spending about 10 percent of their after-tax income on food, including eating out.

Food has gotten relatively cheaper over the decades because technology has allowed more efficient large-scale production, storage and transportation, and incomes have risen too. Of course, food certainly doesn’t feel cheaper today, after years of post-pandemic inflation.

The 1800s did have us beat on a couple fronts. Most notably, housing was much cheaper at the time, but has since grown to a huge portion of our budgets. So has personal spending on health care.

Interestingly, there were also some food items that were cheaper by any measure on our 1897 menu. You could get two pounds of almonds for a quarter. Today, you’d pay around $16. Sauerkraut cost 10 cents a gallon. Today, you’d spend $12.80. Both are much pricier today, even accounting for inflation.

You could also buy:

- 19 pounds of sugar for $1

- 3 pounds of New England mincemeat or 2 pounds of mixed nuts for a quarter

- A pound of cluster raisins for 15 cents

- A pound of currants for a dime

- A pound of chicken for 6 cents

- A pound of roast beef for 7 cents

- A pound of sirloin steak for 12.5 cents

- And a ham for 8 cents.

In short, you could cook two Thanksgiving feasts with all the trimmings for far less than you could buy a 20-pound turkey — $20 on a deep King Soopers sale — today.

If you didn’t have cooking supplies, you could buy a carving knife for 75 cents, a sheet iron roasting pan for a quarter or less, and a turkey platter for 95 cents.

Somebody, build us a time machine. It would probably be cheaper than hosting a big Thanksgiving dinner today. Just make sure to bring your 2025 income.