In September, Mayor Mike Johnston was shocked to find out about some outdated city rules — for example how Denverites need to rat ourselves and each other out when we contract sexually transmitted infections.

“If you have a venereal disease, or you know anyone in the city who has one, you are required by ordinance to call the director of public health within 48 hours,” Johnston told a crowd of tech moguls at the city’s AI Summit that month. “So I can give you her phone number if you need that for any purpose.”

Instead, he used this bizarre rule to demonstrate a point about regulations.

“You always have new rules and new regulations and new ordinances,” Johnston said. “You hardly ever remove them.”

Apparently, his administration is looking to change that, though the timeline is uncertain.

“We’ve been looking into obsolete provisions in the code along with outdated social references, and we do intend to address them,” the mayor’s spokesperson Jon Ewing said. “Some of these ordinances were probably outdated when they were written.”

What does the STI law actually say?

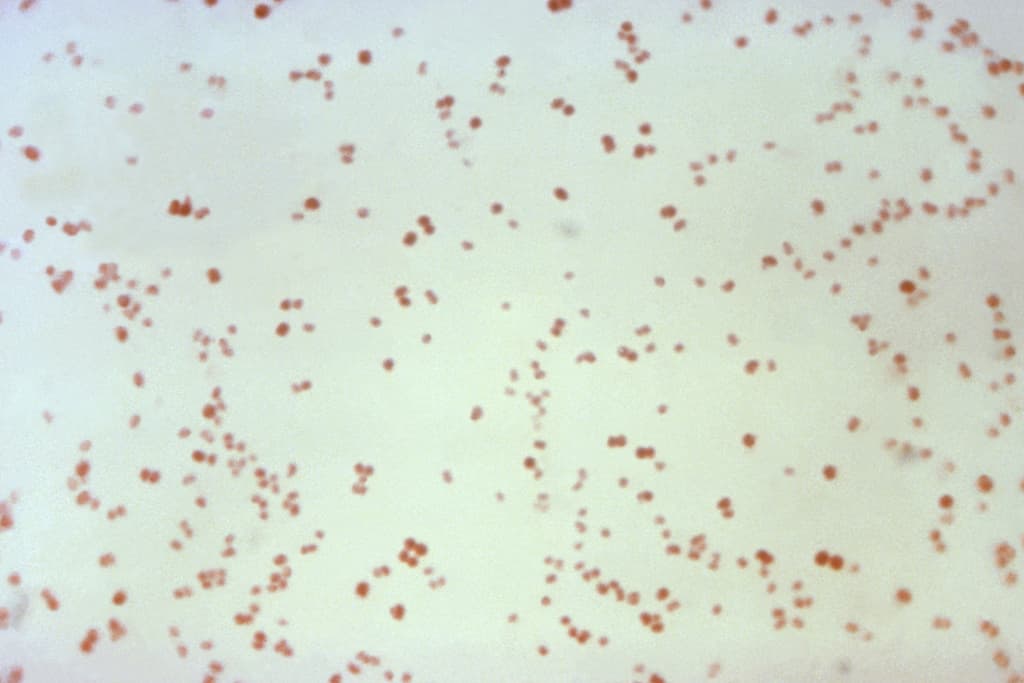

Denver City Council has been feuding over how to address venereal diseases for more than a century. In the 1950s, after a World War II-era outbreak of gonorrhea and syphilis, there was even a heated debate over whether police could detain someone with a sexually transmitted infection.

The current rule, partially established through that debate in the ‘50s and modified over the following decades, works like this:

The Department of Public Health and Environment is charged with using “every available means to ascertain the existence of and to investigate immediately all suspected cases of sexually transmitted infections and to determine the source of such infections.”

The manager of the health department can order people to be tested for STIs, force them to report to qualified health care providers for counseling, and direct people to cease and desist from “specific conduct that poses risks to the public health.”

At least according to the rules, physicians at “any hospital or institution” have an obligation to report people with STIs to the head of the health department with a slew of information, including marital status, occupation, whether the patient handles dairy products and other foods, the name and address of any sex workers associated with the infection, and any habits the person has that could lead to the infection of others.

Legally speaking, people “afflicted with any venereal disease” also have 48 hours to begin treatment with a physician or must report their condition to the head of the health department, providing their name, address and occupation.

Pharmacists who fill a prescription to treat venereal diseases also have 24 hours to report that to the head of the health department.

But the city generally doesn’t enforce any of this.

In practice, Denver has shifted its responsibilities to the state.

While the city doesn’t collect this kind of STI information anymore, health-care providers do have to make similar reports to the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment

Reports to the state do not require the same scope of information (for example, whether a person handled dairy), but they do include personal information: name, address, gender, race, and more.

“We find that the current system of providers and labs reporting sexually transmitted infections to CDPHE meets the needs and goals of the Denver statute, which serves as an additional measure for prevention and protection in Denver, should it be needed,” Amber Campbell, a spokesperson for DDPHE, wrote.

The state uses the information to help stop the spread of STIs — and other diseases.

Since the state receives most STI data, the city doesn’t see many self-reports. But when they do happen, the city has to investigate.

“If someone reported to us that another individual is knowingly spreading infection to partners, we would have a responsibility to investigate and enforce the statute,” Campbell added.

The chances of that happening are slim. Removing the law from the city books, though, would take some time and the approval of the Denver City Council.