Can you prove where you were on June 15, 2012?

More than 18,000 young immigrants in Colorado have done it, and it changed their lives. The law can be a strange, strange thing.

June 15, 2012, was the day that President Barack Obama issued an executive action known as DACA, or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

The change didn't grant anyone citizenship, but it did open new legal options for people who immigrated to the United States as children. For an example of how it works, let's ask Daniel Castellanos.

Castellanos is 20 years old now. He was 11 when his parents brought him from Guadalajara, Mexico to the United States. They paid a smuggler to get them across without authorization from the U.S. government.

For him, DACA arrived just in time: Castellanos' father was arrested about five years ago on a firearms charge, which would eventually result in years of prison time and deportation.

"He’s not coming back," Castellanos realized at a court hearing. "He’s not going to be able to take care of his family."

Castellanos, then in his mid teens, would have to become the family's primary breadwinner, and Obama's order offered a way to do that.

In order to get DACA status, he had to prove:

- That he was in the country on June 15, 2012

- That he was born after June 15, 1981 (Noticing a trend here?)

- That he was younger than 16 when he arrived

- That he was in school or had graduated high school

In all, it can cost from $1,000 to $3,000 or more. The advocacy group United We Dream offers guidance on paying for it.

Here's what he got in return:

- The federal government agreed not to deport him until his status expired (which happens every two years)

- He was allowed to get a Social Security number and a driver's license

That last part was the most important. It cleared the way for Castellanos to work a much wider range of jobs, sometimes several at once – as a janitor, at Wendy's, cleaning cars – while he finished high school.

Besides providing for the family, he could start living "on the record," keeping a credit score and building a bank account.

"I was able to get my mom a car out the dealership, without having to tell a friend, 'Can you get this for me?' " he says.

More than 700,000 people won DACA status by the end of 2012.

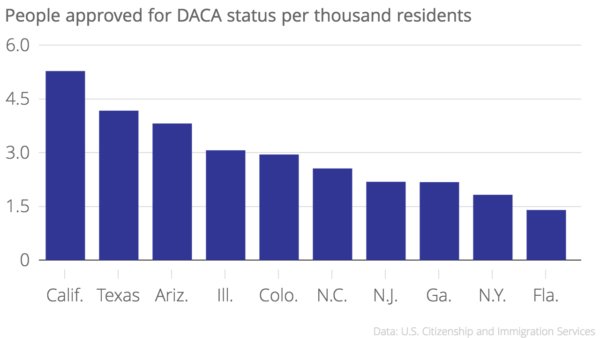

About 16,000 of them lived in Colorado. That's a relatively high number as a proportion of the state's population, ranking fifth in the nation.

It has been four years since this new pathway opened, but advocates say it's an ongoing struggle to get people aware and involved in it.

Besides a lack of money, applicants also can be held back by a lack of documentation. Some people, like Castellanos, can dig up troves of documents from his life in the U.S., including transcripts and report cards from elementary school.

Sometimes, a bit of coincidence can help: One group of teenagers was able to prove that they were in the U.S. on June 15, 2012 because they participated in a religious ceremony at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in Denver that day.

Others aren't so lucky.

"The hard ones are the victims of abuse or victims of crimes," says Belén Albuja, an immigration attorney in Denver. She has seen abusive relationships where "the abuser doesn’t allow her to have anything in her name," preventing the victim from getting DACA status.

Still more people are held back simply because they don't fully understand the process, which can require significant travel and coordination, according to Ezzie Dominguez, regional organizer for the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition.

"The community is still kind of like, 'What is DACA, and how do we apply for it?'" she says. "They kind of confuse it with the DREAM act."

The DREAM Act, by the way, is a proposed piece of legislation that would allow people like Castellanos to apply for temporary and then permanent residency. It has been shot down several times since it was proposed in 2001.

Combined with the election, that leaves DACA up in the air.

Obama created DACA as an executive action, which means that the next president will have the power to get rid of it.

It also faces a spate of legal challenges. Obama in 2014 tried to expand DACA and create a second program, Deferred Action for Parents of Americans, but those efforts are tied up in a U.S. Supreme Court case, as Vox explains.

The possibility of losing the program worries Castellanos. He'll need to renew his DACA status eventually. If he loses it, he'll lose his driver's license. If he loses his license, it gets a lot more dangerous to travel for the business he owns, Clean Car Detail. Suddenly, everyday business could spiral out of control.

"I'm worried about my license. I drive everywhere," he says. "If I get pulled over without that, that’s an automatic ticket. I could get taken to jail."

Most DACA recipients would agree that they have something to lose. About 40 percent got their first car after gaining the protected status, 27 percent got health insurance and 90 percent got a state ID or driver's license, according to a survey by United We Dream.

The consensus among them: 84 percent said they felt more freedom.

One more thing about June 15.

As we mentioned, a lot of DACA's requirements are built around June 15.

Why is that?

Ultimately, the date was chosen for historical significance: It's the day in 1982 that the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited public schools from denying education to undocumented children.