If there were a way to add small, affordable housing units all over Denver without changing the look and feel of a neighborhood, the city would be all over it, right?

Some say accessory dwelling units are the answer that everyone's ignoring. That the city could change the rules to allow more granny flats and in-law units in the backyard, and "instantly create affordable housing." That's not what happened in Denver, though.

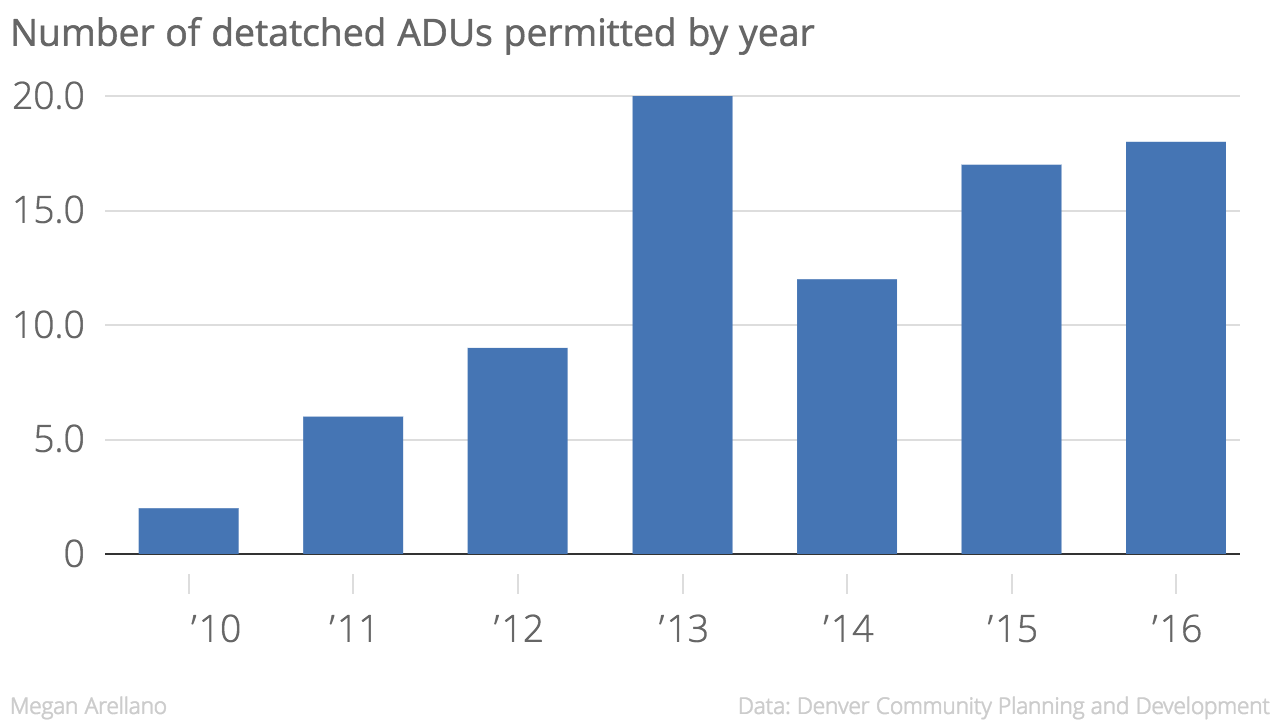

In 2010, the zoning code was changed and neighborhoods were allowed to opt-in to allow ADUs. Since then, only 84 units have been permitted across the city.

But focusing only on the total number of ADUs in Denver obscures a couple things. First, they've become more popular over time:

And second, some neighborhoods have way more ADUs. What's happening in those areas?

Limits on where you can build

Denver only allows ADUs in certain parts of the city. The most cited figure is only 10 percent of the city is zoned for the buildings. Where exactly that 10 percent sits is a lot harder to pin down.

The single-family areas that are explicitly zoned to allow ADUs look like this:

Note that not all areas that allow ADUs will show up in the map. ADUs are also allowed in more densely zoned areas, like multi-unit and mixed-use zones. So that's part of the reason that an area like Five Points ended up with so many, but the zoning labyrinth goes deeper still.

Keeping an historic district vibrant

"We have old carriage houses all over the place from the 1800s in Curtis Park, so it's a tradition for us to have carriage houses and ADUs," said Sue Glassmacher, head of the Curtis Park design review committee.

"But we used an overlay in order to loosen the restrictions in our zone district so that you could build a 2 story ADU on a 25 foot lot and that is the biggest way we encourage ADUs," she adds.

There's a lot of reason that Curtis Park actively sought out easier zoning for ADUs, but it comes down to keep the neighborhood vibrant.

"We're not a museum and we have to keep up,"Glassmacher says. "We need renters in here that can afford to rent. People will rent here, and then they'll buy. We need starter positions."

There's an economic element of necessity too.

It's not cheap to build ADUs but Curtis Park is definitely in a hot area of town. It's also a landmark historic district, and you can't tear down any buildings or pop the top on them. So investors with rental properties are among those building ADUs in Curtis Park, Glassmacher says.

"Some people are looking at making the ADU in the back and then in the front, they rent out the front. They can get more money for the regular house and then they can live in the back,"Glassmacher said.

Still, even with easier zoning and the allure of rental income, Glassmacher says she spends a lot answering questions and being a resource for people. At least four times a year or so, she's correcting someone who thinks ADUs aren't allowed in the neighborhood.

Increasing education alone isn't quite enough

There's only one ADU permitted in Overland Park and it belongs to Overland Park Neighborhood Association President Mara Owen.

Owen picked her house specifically because the area is amenable to ADUs. But she knows that she's in the minority.

"No one goes through the zoning code because they feel like it," she said.

That's why OPNA has presentations at neighborhood meetings making people aware of the option and what it takes to build them. And she might be making progress -- Owens says that now she's noticed ADUs popping up quite a bit more in the last year.

But there's still quite a ways to go.

A survey by CU Denver graduate student Mark Kelley found that 74 percent of the neighborhood is interested in building an ADU. Strange, given that only 41 percent of respondents considered themselves somewhat familiar or more with the buildings.

Until you consider a resident like Patrick Bramley. He's been very interested in building an ADU for himself since he stumbled across someone working on one in the neighborhood.

"It doubles the number of families that have a place to live, and renting costs less than a home," he said. "Plus we have to increase the house density before we use up all the square feet of the earth with houses."

So he investigated how much it would cost him to build one and found that it would be $200,000.

"If I could break even, I would do it. Not many people are going to do it for that reason, but I would."

By Bramley's account, that would mean renting the finished space for $2,500 a month. He's not sure that that's affordable.

This story has been updated to clarify which zones are depicted in the map.