Denver puts about 208,000 tons of trash in the landfill each year, and it diverts much less of its waste than both its neighbors and similarly sized cities.

Only about 18 percent of the city's garbage gets recycled or composted, according to the city's annual report on recycling. That's much lower than comparable cities, including Fresno, California, which diverts 71 percent of its waste, and San Antonio, Texas, which hits 30 percent, according to the nonprofit CoPIRG.

I expected the city might be a little defensive about this, considering the fact that it's been all over the news for days. Not exactly!

Why our recycling rate is so low:

Charlotte Pitt, the city's recycling manager, has a few ideas about why we're so trash-happy.

"Colorado and the Rocky Mountain West have always struggled (to get) high waste diversion rates," she said. First, there's the fact that Colorado has so much space for landfills. "We've never had a landfill crisis," like New York and San Francisco did in the '70s and '80s, she continued.

That means that it's relatively cheap to get rid of trash here, which means there's less incentive to recycle. It doesn't help that the state "does not have any goals or mandates around recycling," she says.

CoPIRG also lists a few main reasons Denver's trash diversion rate is so low.

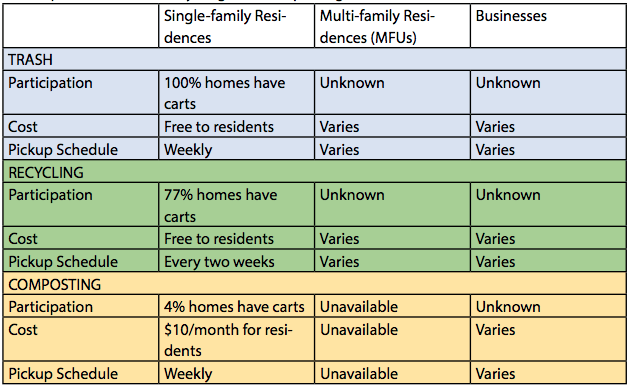

For one, recycling service here is voluntary. It's free, but residents have to request it. About 77 percent of households participate, according to the city.

Second, the city doesn't collect recycling from apartments, condos and businesses. Property owners instead arrange pick-up through private companies, and it's not mandatory.

Third, there is no financial incentive for people to reduce their trash output. Residents pay the same trash fee no matter how much trash they generate.

How the city's trying to change some of this:

The city aims to have recycle bins at every single-family home by 2018, which should get more people participating in the program.

"We did a pilot a couple years ago in one of our lowest participation neighborhoods," Pitt said. "We delivered carts and found that they did, in fact, use them."

However, traditional recycling will only do so much to keep waste out of landfills. That's because recyclables (such as plastic and paper) only make up about 25 percent of the waste stream, Pitt said. The biggest gains may instead be made from composting, which allows organic materials such as food and grass to be kept out of the landfill.

"Every community that has a successful diversion rate usually has some form of organics diversion along with recycling," she said. "That's why we're really making efforts to roll out the composting program."

The city has been rolling out a curbside composting program since 2008. It currently operates five collection routes and will expand in the near future to 11 routes, she said. (Check if you're eligible here. Service is $9.75 a month.)

Each new route can handle about 2,500 homes -- and each one has improved the city's waste-diversion rate by about a half of a percentage point. It would take about 60 routes to cover the whole city, which, if the trend holds, would boost Denver's recycling/composting rate far past 50 percent.

Of course, it all depends on the budget: It takes about $400,000 to start a new route. The monthly fees make the routes largely self-sustaining once they're in operation, but they also hold people back from participating.

What about businesses and apartments?

This is a big unknown, as CoPIRG points out. Because Denver doesn't provide trash service for commercial and multi-family residential, the city doesn't really know if those properties are recycling or not. What if they're all just throwing everything away?

Pitt doesn't see the city expanding its recycling service to these customers anytime soon, but it is doing some research on them. The City Council recently created a licensing program for trash haulers, which will require private collection companies to submit data on how much they're trashing and how much they're recycling.

"Our commitment to council is that we would take a look at the data, see what’s actually happening and then look at what role does the city play in staying out of it or looking at additional policy or looking at additional services," Pitt said.

Anecdotally, she said, it seems like people in many apartment buildings are hungering for recycling services. To that end, the city opened its first drop-off center for recycling in 2015, which collects recycling from people who can't get service. It's at East Cherry Creek Drive South and Jewell Avenue.

The city also has considered collecting recycling more often from homes that do get service, she said, but it's not looking likely. While weekly pickups likely would encourage more recycling, it doesn't seem as cost-effective as composting, according to Pitt.

"When you look at limited resources, our priority really is to get composting in more homes," she said.

Correction: This article earlier said that Denver threw away hundreds of millions of tons of trash. It should have said pounds.