The vast majority of people with HIV in Denver who get treatment see their viral load reduced to the point where it is undetectable. But only 68 percent of people who are diagnosed are in treatment.

There's a lot of reasons for that: pill fatigue, social stigma, homelessness and the instability that comes with it.

Denver will be launching a new initiative in January to find those people who have fallen out of care and try to get them back into treatment. Denver Public Health thinks the best way to do that is by using data.

In doing so, the city will keep the promises it made when Mayor Michael Hancock signed the Paris Declaration in 2015.

The Paris Declaration on Fast-Track Cities launched on World AIDS Day in 2014. Mayors from 27 cities in 50 countries committed to accelerating their local HIV/AIDS responses in order to control the worldwide HIV epidemic.

The program uses data to monitor cities' progress toward four targets: 90 percent of those living with HIV must know their status, 90 percent of those who are HIV positive must be in treatment, 90 percent of those in treatment must have their viral loads suppressed and, lastly, there must be no stigma and discrimination against those living with HIV.

Today, more than 61 cities have signed the initiative, with several more agreements pending.

Denver achieved the first milestone in July and the third, 90 percent viral suppression, on World AIDS Day in December. But since only about 68 percent of people living with HIV consistently receive antiretroviral treatment, that means only about 61 percent of total people living with HIV have their viral loads suppressed.

People with suppressed viral loads don't go on to develop AIDS, and they are less likely to infect others.

Dr. Sarah Rowan with Denver Public Health is spearheading an initiative to bring those living with HIV who have strayed from treatment, either by choice or by circumstance, back into the system.

"We are fortunate that we have amazing clinics in Denver and we have incredible medications," she said. "As providers, it's our job to make sure that they get the best possible care to make them virally suppressed. Absolutely that is a much easier goal to obtain than to keep people in treatment."

Beginning mid-January 2017, Denver Public Health will use information on HIV diagnoses and care that clinics have to report to the state in order to reach out to patients who have been out of treatment for more than one year. The program is based on the CDC's Data to Care model, but tailored to Colorado.

Data to Care is an outreach strategy developed and launched by the CDC in 2014. Thus far it has been implemented in select markets, including Louisiana, North Carolina and Washington, and grants have been awarded to 12 cities over a three-year period to specifically study the program's engagement efficacy in men who engage in sex with men and transgender individuals, according to Brian Katzowitz of the CDC.

"Just collecting information and not using it for public health action is not what we want to do. We want to use it constructively," said Dr. Irene Hall, Deputy Directory for Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Science at the CDC. "We want to use this data to improve the health of people living with HIV."

According to Dr. Hall, the program hasn't been in place long enough to prove its effectiveness. But the CDC seems confident it is a pretty good start, so long as the reported data and testing for HIV patients is consistent.

Colorado has that advantage.

"The use of labs for HIV monitoring purposes was really embraced in Colorado -- with community input and all the appropriate provisions for privacy being protected," Rowan said. "So we are very data-savvy and well positioned to implement this type of program."

The state already monitors HIV care by using patient labs to report all viral loads and CD4 counts, two important markers of HIV care, to the health department. If a patient is missing a lab, the health department knows they are likely out of treatment.

That's when Data to Care kicks in.

The health department can use this information to identify patients who have been out of care for a year or more and determine whether they are still living in the state.

Once an out-of-care patient is identified, the program works to determine how best to get in contact with that patient.

In some cases, as with clinics that have their own retention teams, initial outreach will likely come from the clinic or the patient's personal provider. If those initial attempts fail to engage the patient, then Denver Public Health will get involved with their own personal outreach team.

For the pilot, which will launch at Denver Health, the health department team will be the point of first contact. The program will vary from clinic to clinic.

Although there are no new incentives for the patient to return to care, the value of the data and extra focus on engagement seem to be the factors at play.

The Data to Care pilot program will launch mid-January 2017 at Denver Health and is expected to expand clinic by clinic throughout metro Denver starting in March or April.

With all this personal data floating around, it is important to have safeguards. The CDC mandates comprehensive security protocols before program implementation. And in Colorado, the long established partnership between state reported tests and the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment ensures data is shared securely.

Data to Care should address those diagnosed patients who are out of care. But there are still an estimated one in six Coloradans living with undiagnosed HIV.

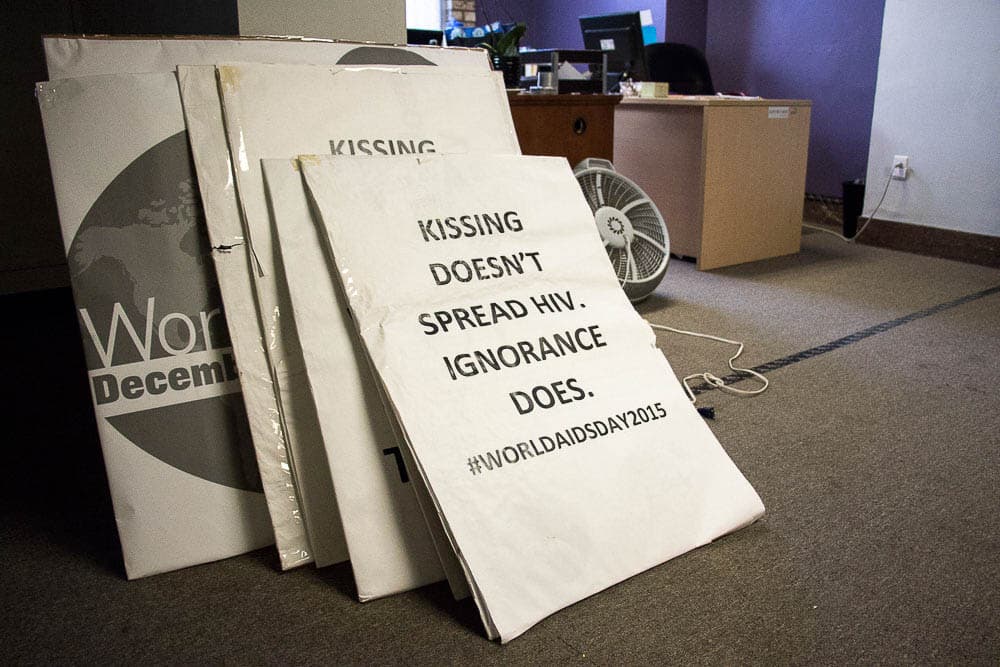

Shannon Southall, executive director of Rocky Mountain Cares, believes eliminating stigma around HIV/AIDS, the final milestone of the Paris Declaration on Fast Track Cities, is the answer.

"HIV has been around for 30 or more years, and we haven't changed the message around testing, but it's not working. We need new messages," said Southall, who herself has been living with HIV for 25 years. "Stigma is what keeps people from getting tested and/or getting into care."

Rocky Mountain Cares is a medical case management organization that helps coordinate care, for free, for about 590 patients living with HIV/AIDS. They help patients navigate what can be a confusing system, practice their own methods of retention and even assist needy and homeless patients with applications for the Colorado AIDS Drug Assistance Program -- which offers HIV-specific drugs at no cost to patients who make up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level, which is $47,520 for a single adult.

Southall believes stigma elimination needs to come from every avenue, from care providers to pharmaceutical companies, from law enforcement to education -- and not just around World AIDS Day.

Treatment for HIV has changed so drastically that today it is a very manageable disease. But Southall said conversation around treatment and prevention needs to change, in the street and at the doctor's office.

"Talking about sex should be just as normal as talking about cigarettes and weight loss," she said.

Denver Public Health maintains that everyone should be tested at least once in their lifetime, regardless of risk. And they have launched several campaigns in the last few years to help promote conversation about HIV prevention, testing and treatment.

The 2015 "Bring It Up Before You Get It Up" campaign sought to start preventative conversations among bisexual and homosexual men and their partners, and encourage testing in the group that is still at high risk for HIV infection. That campaign reactivated near World AIDS Day. "La Red" seeks to reach the broader Latino community through sexual health education.

"I think its manageable to have no stigma by 2030," Southall said. "If we have the right people talking to the right people, if people could be trained in a thoughtful, mindful way of approaching individuals to get them into care -- yes we can do it."

For additional information on HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention, visit Denver Public Health for HIV testing facilities, information on PrEP and PEP (pre- and post-exposure medications), treatment resources and talking points for ending HIV/AIDS stigma.

Multimedia business & healthcare reporter Chloe Aiello can be reached via email at [email protected] or twitter.com/chlobo_ilo.

Subscribe to Denverite’s newsletter here.