A new state study finds no sign of increased overall cancer rates near Rocky Flats, the decommissioned nuclear weapons plant outside of Denver. It's not a conclusive report, and Rocky Flats Downwinders continues to call for deeper study.

The overall incidence of all cancers combined was "no different" in the communities near Rocky Flats compared to the rest of metro Denver from 1990 to 2014, the new Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment study states. There were higher rates of certain cancers, but the report associated those with other causes.

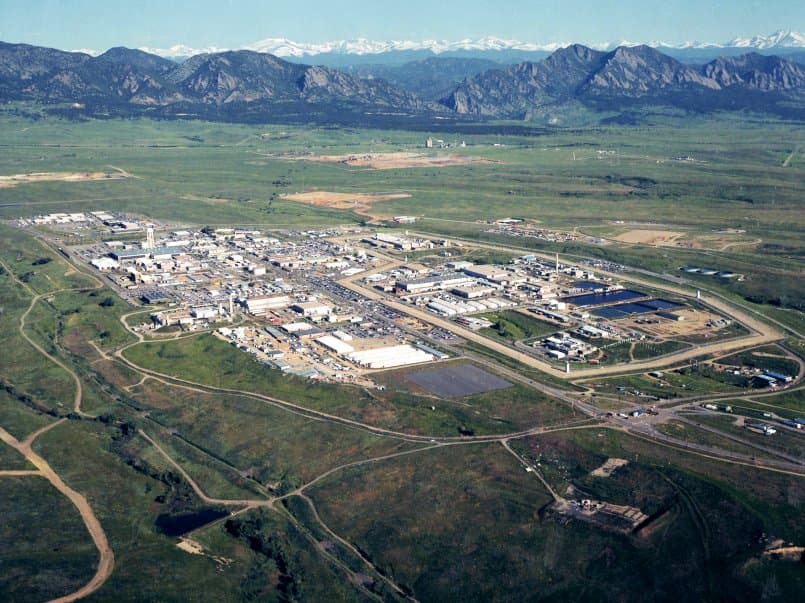

The site of the plant is on Highway 93 between Golden and Boulder, where it operated for nearly 40 years until 1989. Contaminants escaped the plant through "routine air emissions and accidents," according to CDPHE.

The plant's buildings have since been demolished and its waste removed, among other remediation. It's scheduled to reopen as a national wildlife refuge next year.

A federal judge last year ordered $375 million in payments to homeowners to make up for how the plant damaged property values. Meanwhile, development creeps ever closer to the site.

People living near the site have long asked whether exposure to radiation and other dangers from the plant could cause illnesses, especially cancer.

A preliminary survey by Rocky Flats Downwinders and Metropolitan State University found that, among people diagnosed with cancer, thyroid and "rare" cancers were more common near Rocky Flats than nationally. (An organizer noted that it was not "statistically rigorous" because it relied on people to self-report. However, it did capture people who moved away after living near the facility.)

The new state study, initiated early last year, did not look specifically at the frequency of thyroid cancer. However, the state has preliminarily studied thyroid cancer using similar methods and found no signs of elevated incidence, according to Mike Van Dyke, chief of environmental epidemiology.

The official report singled out leukemias, lymphomas and cancers of the esophagus, stomach, colon and rectum, liver, lung, prostate, bone and brain and central nervous system. Those cancers were selected "because they are possibly linked with plutonium exposure or were of special concern," according to the state.

The state report did find elevated rates of lung, colorectal and esophagus cancers in various communities around Rocky Flats. The state report noted that the individuals who had those cancers tended to be drinkers and smokers, both of which are risk factors.

The state report also showed a higher rate of prostate cancer on the edges of Boulder, which the report says may be because wealthier people are more likely to have the disease detected.

And, again, the study found that the rates of all types of cancer combined were in line with expectations.

The report relies on the Colorado Central Cancer Registry, which records all cancers diagnosed here. An earlier state report, published in 1998, had similar findings.

Potential shortcomings:

Attorney Nicholas Hansen, a co-founder of Rocky Flats Downwinders, argues there is a flaw in the study: It captures only people who were living in the area when they were diagnosed.

"You lose people who didn’t have cancer when they moved away -- and then you get swamped by all the people moving in who didn’t have a chance to get cancer yet," he said.

Van Dyke, the environmental epidemiologist, acknowledged that the state study doesn't conclusively show whether being exposed to the plant's emissions would lead to cancer or not.

To draw stronger conclusions, the study would have to get "a better estimate of exposure for each person," and account more for the flow of people into and out of the area," he said. "It would really rely on contacting a whole bunch of people, and it would rely on a lot of time to do that."

The new study, he said, was meant to be "hypothesis-generating" -- one that gives decision makers a clue as to whether a more complex and expensive study is justified.

"The tough thing is, we’re not seeing a huge signal of cancers potentially related to Rocky Flats from this study. It’s hard to justify moving on to a multi-million dollar study," Van Dyke said.

Hansen says that knowing more surely would be worth the cost.

"They need to commission a controlled, random, meaningful study," he said.

"We get contacted on an almost daily basis by people who have had their family decimated by this stuff. Much of the time, they don’t live in Colorado anymore. We don’t know whether their health problems were caused by Rocky Flats, but neither does the public health department."