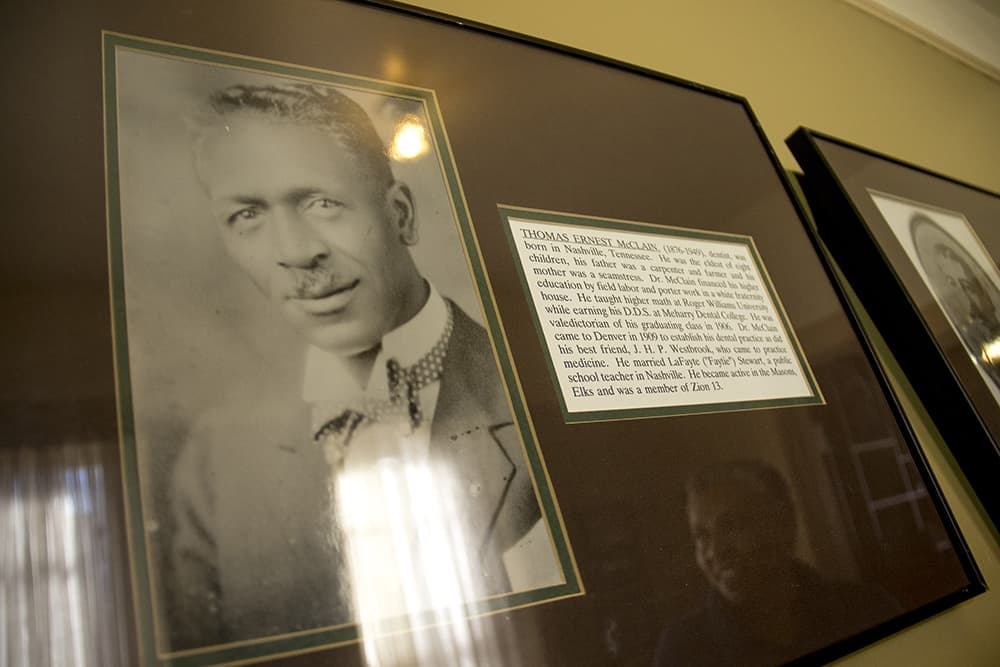

When the Ku Klux Klan was at the height of its power in Denver, one man from Denver's black community infiltrated the group and tried to blunt the impact of its terror. Dr. Joseph H.P. Westbrook's light complexion allowed him to pass for white, and at great danger and cost to his personal health, he attended Klan meetings and relayed their plots back to Denver's black residents.

Terri Gentry knows this story well, and it's not just because she's been working at the Black American West Museum in Five Points for a decade. Westbrook was her grandmother's godfather and her great-grandfather's best friend.

“My grandmother told me this story probably since I was two years old,” she says. Sitting at a long table in the museum's office on California Street, Gentry needs only dive into her own memory to access Westbrook's story.

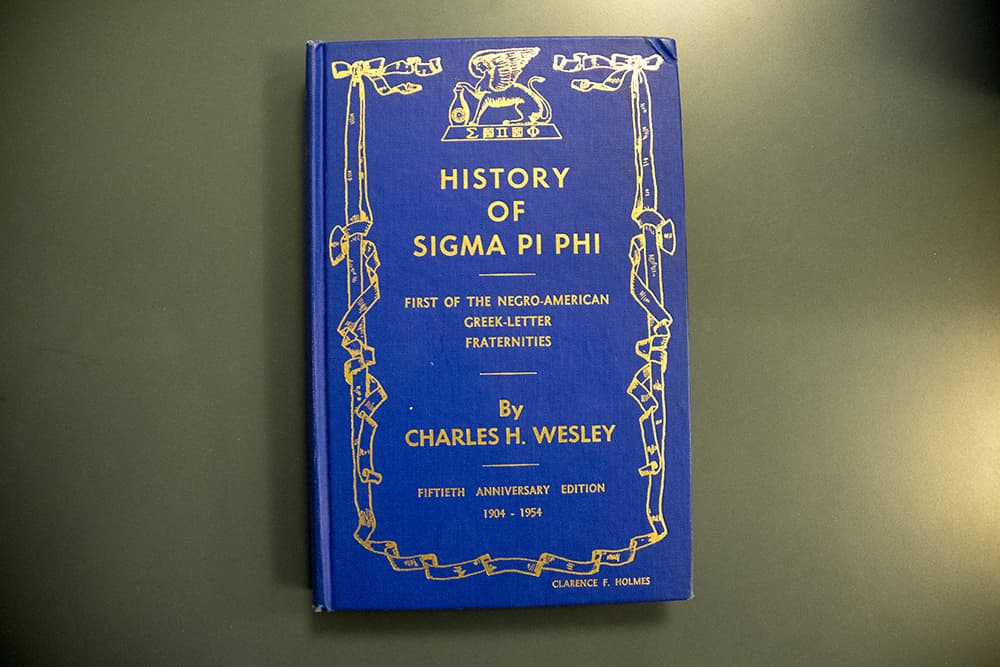

As Gentry tells it, Westbrook came to Denver in 1906 from Mississippi on the heels of other black homesteaders who staked out what is now Cherry Creek. Westbrook was an active member of the fledgeling community and helped to establish Dearfield, an all-black agrarian community in Weld County. He was also a member of the Boulé, the first all-black Greek fraternity that was founded in Philadelphia in 1904 and brought to Denver in 1921.

By the 1920s the homesteaders had been ejected from Cherry Creek so the city could build a dump there, and they instead flocked to the Five Points area for jobs as railway porters and in slaughterhouses. As the community thrived, Denver established "covenants," or racially determined neighborhood boundaries, to keep it from moving east of Downing Street.

At the same time, the Ku Klux Klan was gaining power at the state's highest levels, controlling the state House and Senate and Denver Mayor's Office by 1925.

The Klan, says Gentry, made their presence and power known by igniting crosses on Table Mountain for the whole city to see. At meetings they would plot ways to terrorize Denver's black community, which was fighting to expand Five Points eastward to High Street.

And that's where Westbrook comes in. With fair complexion, Westbrook was able to enter Klan meetings without question.

"They didn’t know that he was a black man,” Gentry says.

For several years, says Gentry, Westbrook listened in to the group's plots and relayed information back to his community. This was an extremely risky endeavor and would not have been possible without extreme confidence.

Gentry says only a small number of people knew about Westbrook's work, most likely the fellow members of the Boulé. Westbrook probably used his fraternal network to tip off community members who might have been targets of Klan activity, in Gentry's words, "taking the wind out of their sails."

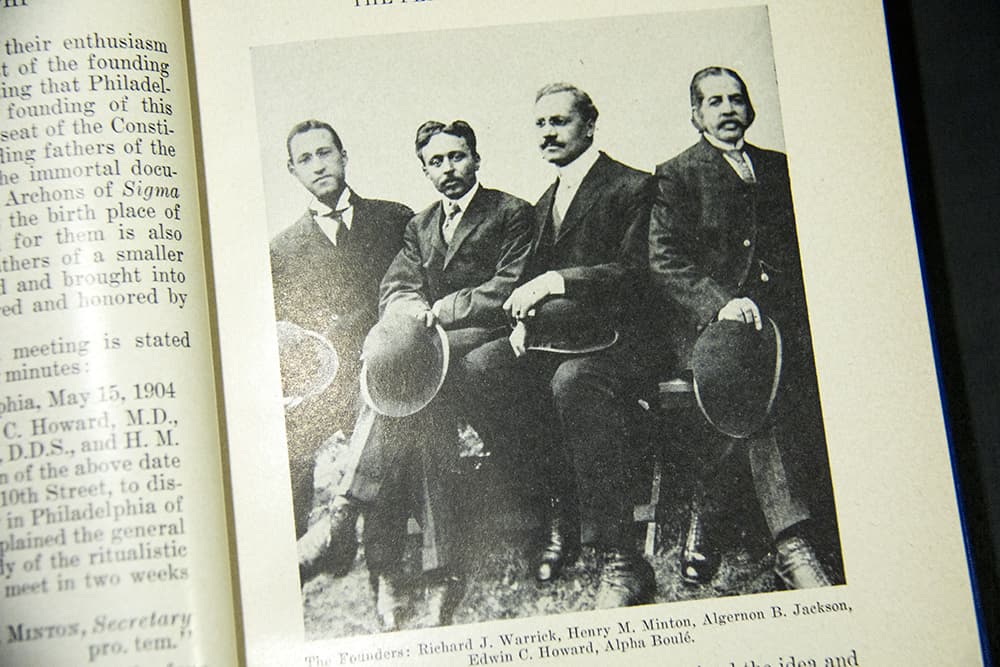

According to a history of the group, the Boulé was formed by black intellectuals, "college men" who were "willing to ally themselves in common causes and to agree to sacrifice for these causes."

While the group's stated goal was to combat isolation among black professionals, founding members' words could point to a larger purpose.

"Concerted action," they proclaimed in their first meeting, "brings about those things that seem best for all that cannot be accomplished by individual effort."

And indeed Westbrook sacrificed much for his clandestine work. He was never caught by the duped Klansmen, Gentry says, but instead suffered a great deal of stress.

"He died 10 years before my great-grandfather," she says. "My grandmother said she thought that the stress of his life really impacted his health.”

Westbrook had every reason to worry. It was an era when people were being kidnapped, beaten, intimidated, run out of town and potentially even bombed by the Klan, and Westbrook could very well have been killed for his espionage.

Today the Boulé is known as Sigma Pi Phi. Local membership includes former mayor Wellington Webb. Other prominent members were Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and W.E.B. Du Bois.

Westbrook's portrait hangs in the Black American West Museum. It's open Fridays and Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. or by appointment. Don't forget to ring the bell when you get there.

More reading for Black History Month

- When black roadtrippers came through Denver in the ’40s and ’50s, this is where they stayed.

- The long-standing Five Points softball tradition you probably never heard of: Twice a year for 63 years, the Denver Randall’s and the Omaha Merchants have faced off in a softball grudge match.

- Charlie Burrell, American symphonies’ first black musician, opened the door for many black musicians to follow in his footsteps, including his cousin — the accomplished jazz bandleader Purnell Steen.

- Martin Luther King Jr. visited Denver for the last time nearly 50 years ago.

He spoke in the University of Denver Arena while wooden crosses and old cars burned outside. - With “cranes up and down” the corridor, changing Denver looks like Welton Street.

- Residential Security Maps were a tool used by the Federal Housing Administration to decide which homes got mortgages. Neighborhoods with white people were favored; neighborhoods of color were definitely not.