Let's say you're building a five-story building on a small lot in a mixed-use zone, which is a thing a developer might want to do in Denver. How many parking spaces should you have to provide on the site? Six? Nine? 16? 24? Why should existing residents have to make room for all those new cars on city streets? What if requiring that much parking led you to assemble a few lots and build even bigger than before?

These are the questions the Denver City Council is trying to answer in its debate over the small-lot parking exemption, a debate that will continue through at least two more meetings. Councilman Jolon Clark held back Monday on introducing his most contentious amendment to a proposal that came out of a working group late last year and that is backed by Council President Albus Brooks.

Two members -- Councilwoman At-large Debbie Ortega and Councilman Kevin Flynn -- were absent, and Clark said he wants to hold the discussion when the full council is present. April 3 is the next chance to do that. Those extra voices and votes could be the difference between Clark's amendment passing or Brooks' proposal moving forward. Either way, the changes will require a second vote and a public hearing.

Each of these proposals rolls back a zoning provision that's been in place since 2010 but that was not used until last year. Clark's proposal rolls it back more than Brooks'. This is the aforementioned small-lot parking exemption. The exemption allows projects on lots 6,250 square feet or smaller in certain mixed-use zones to not include any parking on-site, and some developers were using the exemption to build large apartment buildings with little or no parking. This, in turn, upset some neighbors who felt it was already too hard to park on their streets and that long-term residents were being asked to carry the burdens of new projects that enrich developers.

In the face of this controversy, the Denver City Council approved a moratorium last year on use of the exemption and convened a working group to study the issue. That working group produced the Brooks proposal, but we can't really call it a consensus because four neighborhood representatives wouldn't sign on. That brings us to where we are today.

The City Council voted Monday to extend the moratorium to May 26 to allow for more discussion. The City Council also voted unanimously to adopt two amendments proposed by Clark. One would require a neighborhood notification process when a developer wants to use a parking exemption. The other added a promise by the city to develop what's called transportation demand management for new buildings. That means developers would be required to include features that would reduce the need for residents or workers to use cars and make it easier to use transit or bikes, but all the details would be worked out in some future public process.

There are a little more than 3,300 small lots in Denver in the zoning districts to which the parking exemption applies, but some portion of those aren't eligible because past development patterns have resulted in parcels being combined. (Basically, they aren't "small lots" anymore, even though they look that way on a parcel map.) So we're talking about a relatively small part of the total land area in the city, but the discussion has larger implications for how Denver responds to neighborhood concerns about the impacts of development and how far the city is willing to go to build for a less car-dependent future.

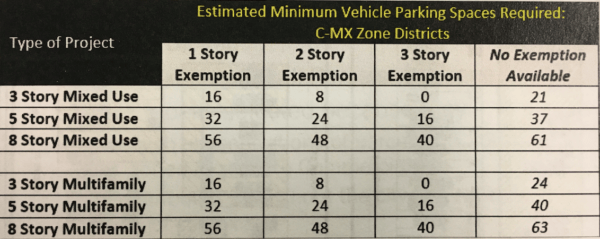

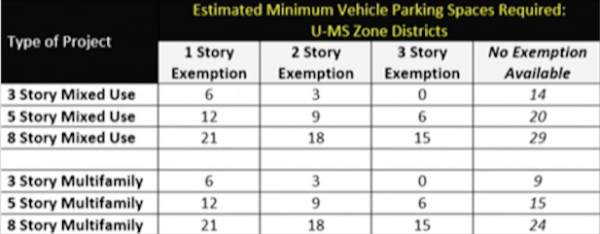

Both proposals don't require any parking for existing buildings, even when they're significantly remodeled, added to or repurposed. This was a major concern of Historic Denver, which didn't want to see older buildings demolished just to meet parking requirements. Both proposals allow buildings along transit corridors to get away with less parking than buildings farther from bus routes and light rail, and both proposals exempt the first few floors of a project and add in parking requirements as buildings get taller. Brooks' proposal exempts the first three stories along transit corridors and the first two stories outside those corridors. Clark's proposal exempts the first two stories along transit corridors and only the first story outside the corridor.

Here's what that looks like in practice:

Roughly 60 percent of the small lots are in the C-MX zone. A five-story building in a transit corridor with commercial on the first floor and apartments on the upper stories would need to provide 16 parking spaces in Brooks' proposal and 24 in Clark's. The same building further from a bus route would need to provide 24 parking spaces under Brooks' proposal and 32 under Clark's.

The U-MS zone doesn't require as much parking as C-MX. The same five-story building in a transit corridor would need six spaces in Brooks' proposal and nine in Clark's and nine or 12 spaces respectively outside the transit corridor.

Joel Noble, a member of the Planning Board and president of Curtis Park Neighbors who spoke on his own behalf, told council members last week at the Land Use, Infrastructure and Transportation Committee meeting that many of these properties just won't fit that much parking. They're generally 50 feet wide, which means you can fit five parking spaces in a row off the alley. That's unless you go underground, which adds a lot of cost that in turn makes the housing units more expensive.

Requiring more parking creates an incentive to assemble lots and build larger buildings -- just to get room for on-site parking, he said.

"Both of these proposals will reintroduce an incentive to assemble lots," he said. "You hear, 'I don’t recognize this city anymore with all these big things being built.' And do you want to speed that up?"

Clark said it's impossible to "predict the unintended consequences" of changes to the parking requirements. Developers are responding to a variety of incentives and market forces, and they might assemble lots and build big or keep a project small to avoid triggering parking requirements. The residents he represents off of South Pearl Street are already facing major parking impacts with the current development patterns.

John Riecke told the council they should keep the exemption just as it is -- no parking requirement at all. Neighbors who are complaining want to force new residents to provide their own parking so that they themselves don't have to do that very thing.

Councilman Rafael Espinoza reacted strongly to the idea that older residents are being selfish when they resent the impact of new development or that the elected officials who respond to their concerns aren't thinking critically about housing and transit.

"It's not just the Johnny Come Latelies who have the trump card over everything we do," he said.

In the meantime, Pando Holdings, the developer of 108 microunits at 16th and Humboldt, one of the projects that got people worked up about small-lot exemptions in the first place, has found off-site parking locations to mollify the neighbors and hedge against the possibility the market isn't quite there for so much car-free living.