It would start in the streets, water beading together on the pavement of Park Hill and sloughing into the gutters and underground pipes. It might take an hour before the drains beneath the pavement were full.

Soon, Leetsdale Drive would become a curving funnel, driving water down toward the open fields of City Park, where it would pool into a lake and then escape downhill. With no natural route to escape from northeast Denver to the South Platte, the floodwater within hours would make a river through the neighborhoods, piling higher and faster as it crashed into the valley.

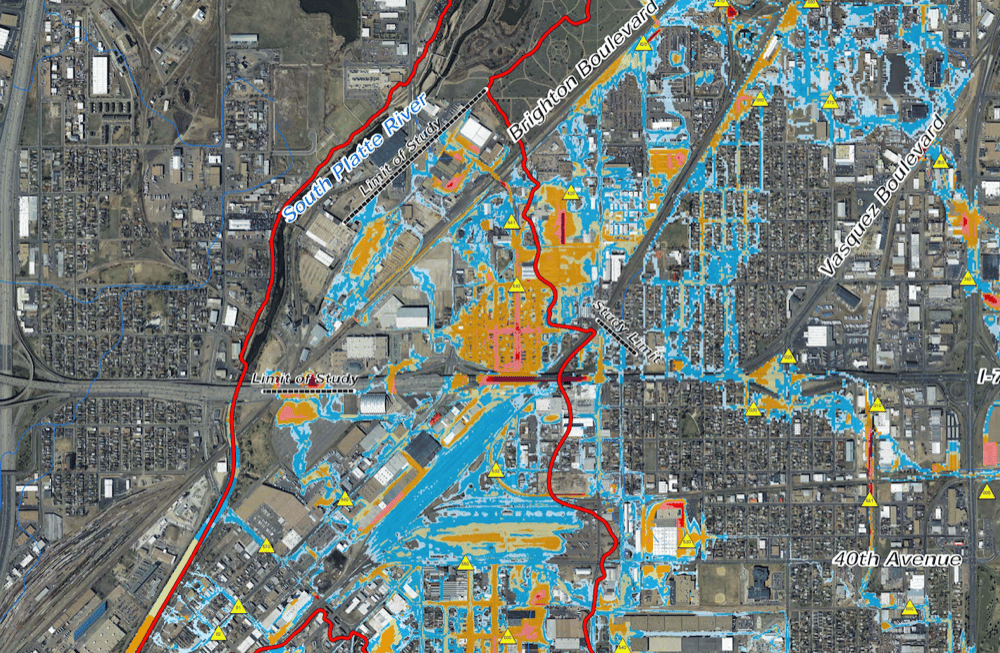

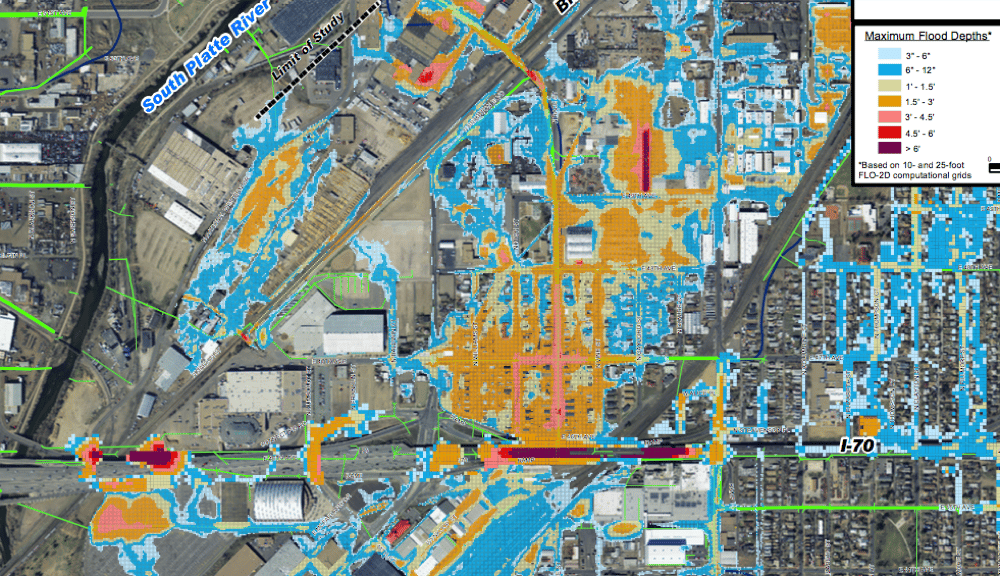

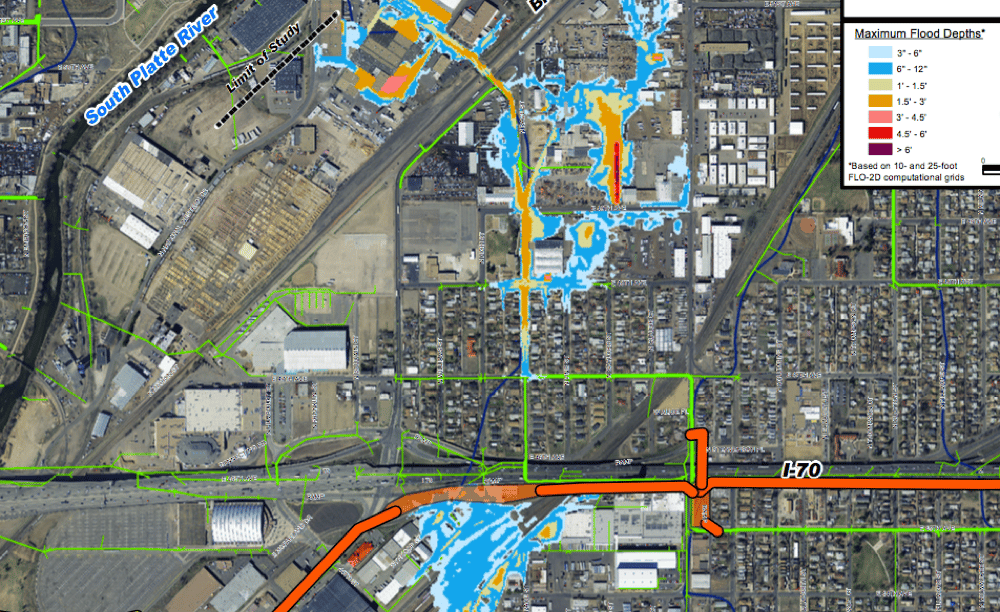

"You would have high velocity of water, six feet in depth or greater," said Jenn Hillhouse, a project engineer for the city. She was describing the 100-year flood, a theoretical catastrophic event that would send a crush of water flooding into low-lying neighborhoods and straight across the path of Interstate 70.

City engineers say that one of Denver's hottest redevelopment zones would be swamped in a matter of hours by a flood of this size. Nearly $300 million of new pipes, channels and wetlands are supposed to safeguard the city against this scenario, according to city engineers.

The trouble is, not everyone believes them.

"This water doesn’t have anywhere to go," said Jamie Price, program director for the city's massive new floodwater plan.

Along High Street, the pressure in the pipes might blow manhole covers from the pavement, fountains of water spraying behind them. Before long, it would inundate the railyards and the underpasses and then swamp some of the bungalows of Elyria, trapped between the highway and the river, with some four feet of water. You might hear the unnerving sound of metal and rock rolling beneath the standing waves.

"It’s the energy," Price said. "It’s the destructive force of the water. ... It starts taking homes off foundations."

By the apex, swift-water rescue teams would be jetting out into the flood, their inflatable boats dodging trees, cars and even homes caught in the flow as they searched for trapped survivors.

"It would be catastrophic," Hillhouse said.

And yet in Elyria and Swansea, the neighborhoods in the center of the projected flood path, there is doubt and suspicion.

The "Platte to Park Hill" flood-control project has come in for its share of skepticism in these local circles, despite the fact that it purportedly shields the entire area from the monster storm described by city officials. Hoping for answers, we canvassed the area and reviewed the city's data.

What we found was a community that fears it will be swept away, but not necessarily by the floods. They see the pieces being laid for an era of redevelopment, especially the expansion of I-70, that they fear will leave their homes unrecognizable.

"For them to try to say they’re solving our flooding -- I mean, my God, I'll take the floods before the highway," said Drew Dutcher, president of the Elyria-Swansea Neighborhood Association.

"I’ve listened to the city engineers, and to them, the sky is falling," Dutcher said.

He's lived in Elyria for a decade and hasn't seen the kind of monster storm that city officials are describing. At worst, he said, "you still can kind of drive through it." And yet the city's projections show that a 100-year flood could put almost five feet of water on his block of High Street and up to three feet around his home.

This dissonance isn't uncommon. Many of the newest residents don't think of their home as a flood plain. Michael Lanford, a custodian and recently arrived renter in Elyria, figured that the floods tended toward Globeville, on the opposite side of the river.

"I didn't think this place got hit," he said.

With time, though, people get more familiar with the floods.

"You know, we haven't had a rain for ages, it seems like," said Bettie Cram, who has lived in the area for 65 years. But when it does, she said, a storm can flood onto the side-streets. "Sometimes, I have to take my shoes off, if I’ve got good shoes on."

Sylvia Valdez, who has owned Ciancio Liquor store for 40 years, also takes that can-do attitude -- a certain expectation that life in the lowlands occasionally brings the flood.

"There could be some water going down the street, but nothing that would stop you," she said of her experience.

Dutcher, the neighborhood president, is receptive to the "latté" theory popularized by Adrian Brown, a local civil engineer.

"You’re solving an event that happens maybe once a year, and you’re doing all of these radical changes. ... When you have a storm, go sit in the cafe with the latté," Dutcher said.

The city engineers say it's hard to grasp the threat.

"I think there’s maybe even an awareness issue. Some people may not even realize an old creek went through there," said Price, the city project director.

Let's stop here for a little history. Elyria and Swansea both began as independent communities on the banks of the South Platte. Elyria eventually built its own city hall, commercial district, saloons, shops and churches.

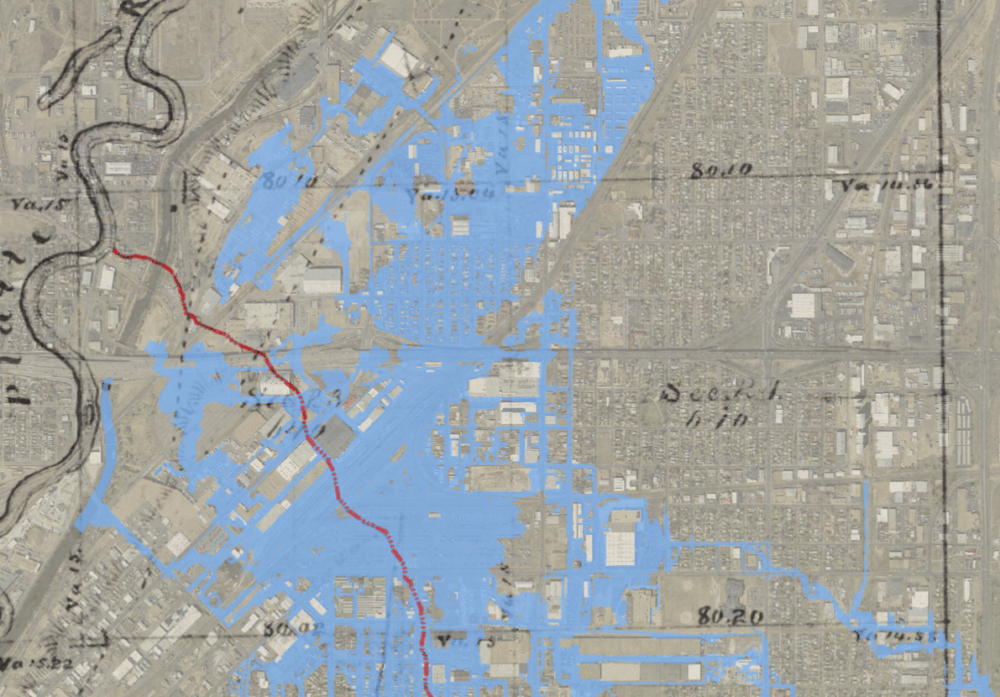

Just southwest of Elyria, a creekbed cut down from what's now City Park, directly through the future site of the Denver Coliseum and into the river. The area's early planners probably didn't think much of crossing it with rail lines, residential blocks, warehouses and factories.

"Over the 150 years or so of development in Denver and in that basin, that was covered up," said Shea Thomas, a program manager with the Urban Drainage and Flood Control District.

The pattern of development that emerged in the low industrial area makes flooding and water quality particularly bad, according to Kelly Leid, director of the office of National Western Center.

"Basically, water today flows across these big massive industrial sites in sheet flows toward the Platte," Leid said. "Water quality is pretty much nonexistent. It’s just moving across the sites toward the Platte."

In modern design, no area larger than 130 acres should lack drainage in a major channel. In the Montclair basin, a good part of nearly 6,400 acres doesn't have a proper channel, Thomas said.

"If Montclair were to be developed today, there would be a creek," she said. "They would have kept development out of the 100-year floodplain associated with that creek."

Eventually, the engineers say, the Platte to Park Hill "backbone" could allow for flood control farther south in Cole and Whittier. (Those southerly areas will get only "secondary" protection in this initial phase, but that could be strengthened later, according to the city.)

So, why haven't these longtime residents seen the kind of flood the city is describing?

Well, the Front Range has indeed had storms of the magnitude the city is warning about, such as the 2013 front that drowned Boulder in 26 inches of rain. That event was considered a 1,000-year rain event and produced flows five times greater than 100-year flood levels in some mountain drainages. However, none have stalled in just the right place to cause a disaster in the Montclair basin, according to the city engineers.

During that same 2013 storm system, the city had its closest call in recent years when a heavy storm instead tracked east to Stapleton. It was easily deflected by the drainage system in that newly built community -- which, like practically all new development, is built to 100-year standards, Thomas said.

Now, that's only the standard for new construction. It's extremely costly and difficult to retrofit an area with major drainage. A city-wide attempt at 100-year coverage "is not practical," according to the master drainage plan.

However, the Montclair basin likely got a priority boost for two reasons: First, it's the largest in a multi-county area that doesn't have some kind of natural drainage.

And, second, the Colorado Department of Transportation is also putting a boatload of money into the Montclair project because it will also protect their Interstate 70 project, which will run in a trench right through Elyria and, therefore, the lowest part of the riverside basin.

"A cloudburst, a heavy rainstorm, it comes from everywhere, and it goes underneath I-70," said Leo Branstetter, owner of a former hearse and ambulance garage at 47th and Brighton. "I don’t think they can improve that until they do this big drainage deal."

The I-70 connection alone has understandably driven opposition to the project. The friend of my enemy is my enemy.

As a result, project engineers have faced activists' detailed questions on a range of topics, from its designs for Globeville Landing to the looming remodel of City Park Golf Course to better accommodate flood waters and the creation of a long open channel along 39th Avenue. (Find a full summary of the projects here.)

To Christine O'Connor, a critic who has studied the project extensively, the project is tainted by its entanglement with Interstate 70.

"In theory, having protected riparian corridors that can handle extreme events is wise. Look, for example, at the extensive work restoring the Westerly Creek flood plain," she wrote in an email.

"But this was able to be done before development or along with development of Lowry and Stapleton. This P2PH project is not comparable," she continued. "It is an effort to pretend this is about restoring a watershed when, in fact, it is an engineering project to transport water from as far away as Colorado Boulevard to the South Platte through a manmade system of culverts and channels designed to protect the I-70 project."

And she's skeptical of the idea that P2PH's benefits will one day reach neighborhoods south of 39th Avenue. "My guess is we will continue the same slow pace of localized fixes," she wrote.

One way or another, something interesting happens when you reduce flooding in an area.

Developers get more interested.

"I’ve chased off three dozen buyers in the last few years -- just run them out of here," Branstetter said. "It's more than a potential ... A lot of the old-timers, they’re selling out, pulling up stakes and getting the hell out of here."

Now, that developer interest is obviously a result of way more than just the flood control plan, which was only introduced in 2015. Elyria-Swansea is just downstream from the development zone known as River North, and a lot of the public and private spending there is expected to spill into Elyria-Swansea.

For example, the current reconstruction of Brighton Boulevard -- complete with sidewalks and bike tracks -- eventually is expected to extend through Elyria-Swansea to Race Court. And the city is on the cusp of a major redevelopment of the National Western Center.

However, this big flood-control plan is also likely to incite development for two reasons. First, it shows the administration has its eyes on this area, especially combined with the plans for Brighton and the National Western Center. Second, flood control literally makes development cheaper. The building code requires that finished floors be elevated 12 inches above the 100-year flood flow. Across the river in Globeville, which will not be protected by this project, the city is requiring that some structures be built several feet above the ground, as The Denver Post reported.

"Developing a site or building new homes or new businesses -- they all have that additional cost incurred," said Price, the city staffer.

It's hard to say just how much developers would save with the new flood controls. Certainly, a few recent large-lot buyers I contacted didn't even know about the flood-control project. But it is one more factor in developers' equations.

"While it didn’t influence our site selection, it has helped, I think, in attracting some high-quality, experienced vertical developers to our circle of partners," said Tony Pickett, a vice president for Urban Land Conservancy, which is building up to 560 residential units at 48th and Race.

"It gives everybody confidence. If there’s public investment going into these areas, whether it’s the commuter rail line or stormwater infrastructure, it’s certainly worth investing in those areas for vertical developers," he said.

So, there's a paradox for Elyria-Swansea.

The city's $300 million flood-control plan may well afford them some protection, at least according to the engineers' modeling.

But, in doing so, it will protect a highway that they've been fighting for years -- and while it may not be a deciding factor for developers, it may well signal to them that the area's ripe for redevelopment.

"During huge spring storms, we’ll have a little less flooding -- but you’ve destroyed the Elyria neighborhood," Dutcher said.

Cram, the long-tenured resident, also sees an era of change coming. "It’s going to be a completely different area here."