"So the executive summary is a smiley face?" state Sen. Kevin Lundberg asked as the Joint Budget Committee prepared to hear the latest forecasts from Colorado's state economists Tuesday.

Not 100 percent a smiley face, but economic growth should continue to be positive in the near-term and significant legislation passed earlier this year has relieved a lot of pressure on the budget.

However, there are some surprising constraints on the state economy, an unexpected dip in revenue projections and plenty of uncertainty from Washington. And the 6.5 percent budget reserve that's theoretically required by law isn't fully funded.

Here are five key takeaways from the economic forecast:

Low unemployment and high housing costs are limiting economic growth.

This has been noted in several recent forecasts, but it's interesting to me every time. Two of the indicators of our strong economy -- the lowest unemployment rate in the country and rising housing prices -- are also serving as a brake on our economic growth. Businesses can't expand because they can't hire enough workers, and housing prices make it harder to entice workers to move to Colorado.

"The economy is at capacity," economist Larson Silbaugh told the Joint Budget Committee.

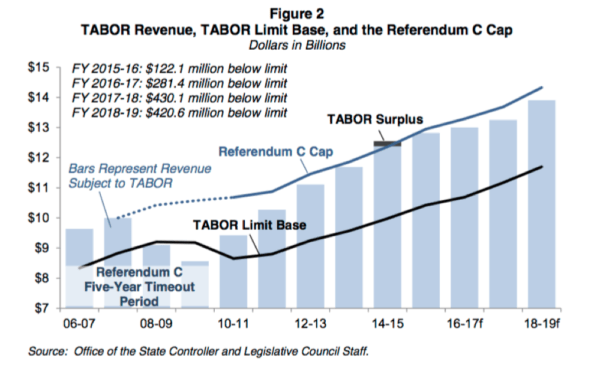

Colorado won't issue TABOR refunds for at least the next several years.

SB-267, the omnibus bill that dominated the second half of the legislative session, is the main reason for this. For several years previously, the state faced the prospect of having to return money to taxpayers under the Taxpayer's Bill of Rights because Colorado was collecting too much revenue. However, a lot of that revenue came from something called the hospital provider fee, which was charged on patient revenue and then returned to hospitals to cover the costs of treating Medicaid patients. The hospital provider fee money couldn't be used for refunds, so this would have meant cutting other parts of the budget to find money for refunds or reducing the amount of the fee -- and federal matching money that goes to hospitals. It was a mess.

SB-267 reclassified the hospital provider fee into an enterprise fund, like a government-run business that isn't subject to TABOR. It also lowered the cap that applies to the total amount of government spending allowed in Colorado (lots more details here), but by much less than the amount generated by the provider fee.

The upshot: Colorado can collect more tax revenue as the economy grows without bumping into the cap and having to return money. This trend continues as far out as the forecast goes, which is summer 2019.

This doesn't mean budgeting will be easy next year, but it relieves a major headache that dominated budget debates for the last several sessions and allows government to grow more than it otherwise would have.

People paid less state income tax than expected, but not because they were making less money.

In fact, withholdings from wages are actually up, meaning low unemployment seems to finally be having an effect on wages. That's the good news.

But many taxpayers held off selling assets and making other investment decisions that would have generated tax liability due to the expectation that there will be some sort of tax changes out of Washington, D.C., that would mean they would pay less in the future. We don't know right now if that tax reform will happen or what it will look like or how action or inaction will shape taxpayer behavior over the next year or two.

In the meantime, state government has less money to work with than was expected in March.

This isn't an immediate crisis. The state is just carrying a smaller reserve than it should. The exact figure is always a moving target until the end of a budget year, as revenues and expenditures never exactly match projections, and the governor's office and the legislature's economists produce slightly different forecasts. But it's likely to be somewhere between 3.7 percent and 4.8 percent for the budget year that starts July 1. By law, it's supposed to be 6.5 percent, but it can get pretty low before the governor is required to have a plan. That reserve gap gets carried forward, and budget planners want lawmakers to fully fund the reserve before there is another recession and revenues really take a hit.

Funding the reserve would mean less money available for new spending in next year's budget.

Next year means the 2018-19 fiscal year that starts next summer. That's the budget lawmakers will work on when they reconvene in 2018.

Henry Sobanet, director of the Governor's Office of State Planning and Budgeting, strongly urged lawmakers to prioritize the reserve. Without adequate reserves, the state is much less prepared to handle a downturn in the economy without drastic cuts. For context, the city of Denver carries a 15 percent budget reserve, so the state's goals -- which aren't being met -- aren't even particularly conservative.

"It is absolutely essential that we get back up to our reserve level ahead of the next recession," he told lawmakers on the JBC.

You can read the full economic forecast from the Governor's Office of State Budget and Planning here and the full economic forecast from the Colorado Legislative Council here.