Robert Joseph is 50 years old. He's been homeless for all of his adult life.

"I’ve had a lot of traumatizing things in my life, after so many years of living on the sidewalk, abandoned buildings to buildings, jails to jails and prisons to prisons," the 50-year-old said, snacking on a muffin outside a chain bakery on the 16th Street Mall.

“My mind don’t stay straight. I see and talk to dead people. It’s like my ma’s sitting there right now, my brother, my dog, Otis," he continues. "I’ve been told that I don’t act crazy, I don’t seem crazy ... You’ve got to maintain something."

Joseph is "chronically homeless." He keeps clean clothes and a friendly demeanor, but he almost perfectly matches the common idea of homelessness: a bearded older man, beset by mental illness and alcoholism, who has nearly given up hope of a different life.

In fact, chronically homeless people are only a small subset of Denver's homeless population: They are about 20 percent of the metro's 5,116 homeless people, according to the latest survey of local homelessness.

But chronic homelessness comes with disproportionate costs both for the people living it and for society. A widely cited study found that emergency services and jail time cost $40,500 a year for each chronically homeless person with a severe mental illness in New York.

Those costs have inspired a long and somewhat successful campaign by local and national governments. The federal government has increased spending on permanent housing for the chronically homeless by almost 50 percent since 2009.

Meanwhile, federal money for the "transitionally" homeless has been reduced, arguably at the cost of homeless families, as Kriston Capps reports for CityLab. (However, the government has ramped up support for rapid rehousing of newly homeless people and families to a lesser extent.)

Overall, that focus on chronic homelessness may be working. Chronic homelessness across the nation is down by 35 percent from 2007 to 2016, according to federal statistics.

Denver also has seen something of a decline. The chronic numbers reported today are about 25 percent lower than those recorded in 2004.

However, the Denver metro as a whole reported just more than 1,000 chronically homeless people in the one-day survey, its highest number in at least a decade.

We don't know yet if that spike will show up in the national figures or what drove it. It's extremely difficult to reliably count people who don't have a steady residence, and the data is collected on just a single night. So this may be an anomaly -- but it does illustrate the fact that chronic homelessness is not disappearing.

What's being done?

Here's one interesting approach to chronic homelessness: The Colorado Coalition for the Homeless is intentionally tracking down the people who end up in the hospital, jail and other services more often, then putting them in housing.

They'll be placed in 210 new housing units. Most are under development, including 100 units to be managed by the Coalition near its 21st and Champa headquarters and 60 units by the Mental Health Center of Denver near South Federal Boulevard and West Iowa Avenue.

The city of Denver is coordinating the money for the program, which comes from philanthropic institutions. It will use $8.7 million from the institutions and $15 million in federal funds.

And the big catch is that if the program succeeds, Denver will take the money it saves on jail and health care and repay it to the philanthropic lenders. So, the lenders are incentivized to help the city drive down homelessness-related costs.

"They’re looking at, 'Do the costs go down when you house people?' We have always found that that’s true," said Cathy Alderman, a spokeswoman for the coalition.

"Once someone’s stably housed, they may access more health care up front. They eventually stabilize and get into more regular routines."

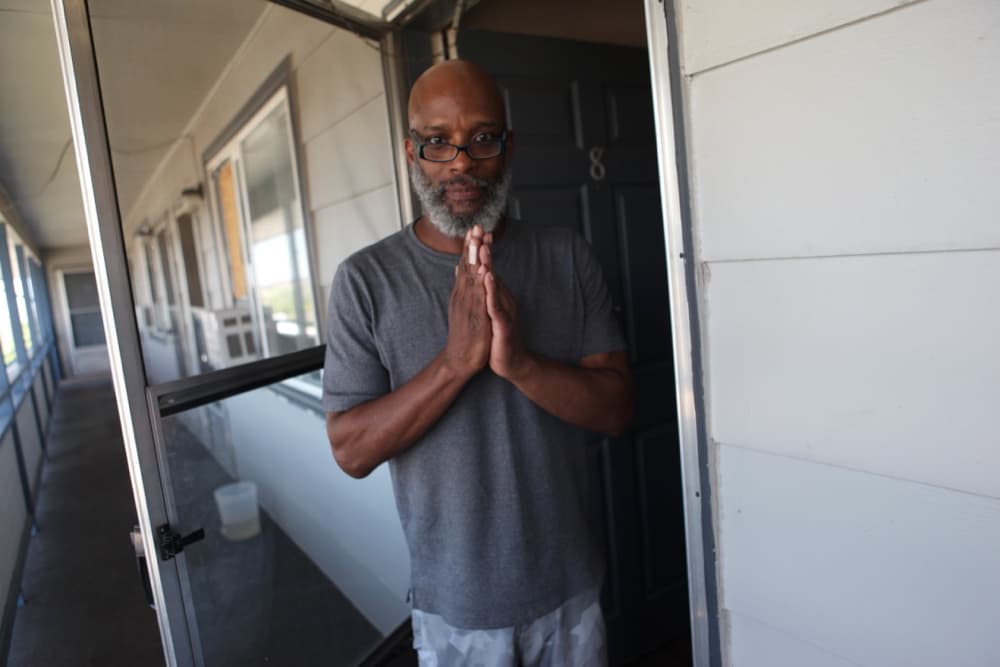

I recently met Reggie, 57, who got his own apartment through the program. He's been there for nearly a year, resting and recovering from decades of on-and-off homelessness.

Reggie has been to the hospital more times than he can count for injuries sustained in fights and for long-developing injuries from a lifetime of hard work. His place is immaculate, and he's working on meeting the criteria for his hip replacement surgery: no drinking, no smoking. He looks back on dark days and sees something different ahead.

"I’m not a part of the environment, so to speak, that’s out there with the filth and the muck and the scum and everything else they throw at you," he said. "I didn’t need a program. I needed a place to stay, or I’d be dead or in jail."

Overall, the city expects up to a 40 percent reduction in jail time for participants.

What else we know about homelessness in the Denver metro:

The following statistics came from this year's point-in-time report.

Chronic homelessness:

- About 56 percent of the chronically homeless reported a mental illness.

- About 47 percent reported substance abuse.

- About 22 percent said they were the victims of domestic violence.

General homelessness:

- About 75 percent said their last permanent residence was in the seven-county Denver metro.

- 52 percent are part of a household with a working income.

- 43 percent were in transitional housing, defined as short-to medium-term living situations, often provided by nonprofits. (It still is counted as homelessness.) That's a significant increase from 2004.