Last Thursday, Lon Stanley of Vidor, Texas, put an unusual item for sale on eBay: a zinc-tin griffin that likely once stood atop an 1800s-era courthouse in downtown Denver, listed for $250,000.

"It HAS to be one of the crown jewels of Denver," Stanley wrote. "This is more than likely the only remaining one of eight original Griffin sculptures left in existence."

While Stanley has cited various documents that he says proves the piece's provenance, I'll leave it to a real historian to decide whether or not the item actually came from the courthouse. I learned in my own research that the courthouse became an early symbol of turmoil over the city's growth. Its demolition caused not only the griffin gaggle's diaspora, but also a wave of angry Denverites protesting modern development.

When the Arapahoe County Courthouse (often referred to as the "old courthouse") was constructed in 1883, Denverites complained.

"Back in ’83 a good share of the people were mad because they said the new courthouse was being built way out on the edge of town. And it was, too," wrote Denver Post editorial board member L.A. Chapin in 1932.

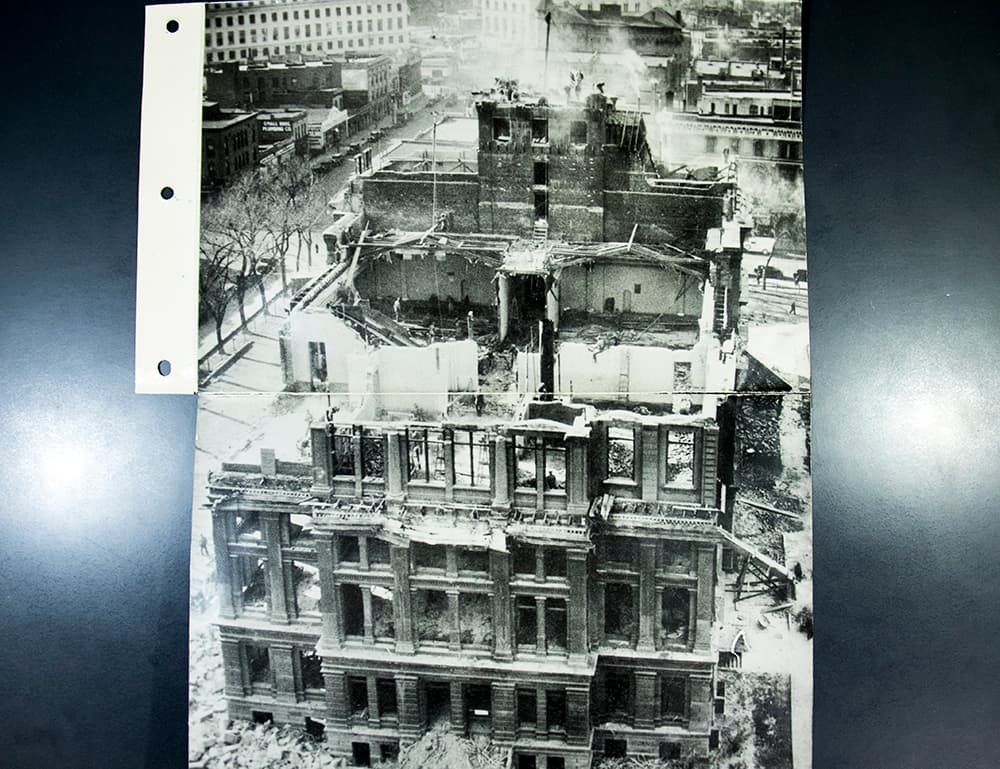

The domed municipal building on 16th Street and Tremont Place, even in the 19th century, became the subject of what seems now to be a tradition of resistance to change. By the time it was slated for demolition in 1933, Denverites had accepted the structure and now lamented its disappearance.

"History is repeating itself in the manner of new municipal buildings for Denver," said one Rocky Mountain News report from 1932. "Traditionally, it seems, there must be five years of strife and opposition between the time plans are first broached for the buildings and the actual breaking of ground.”

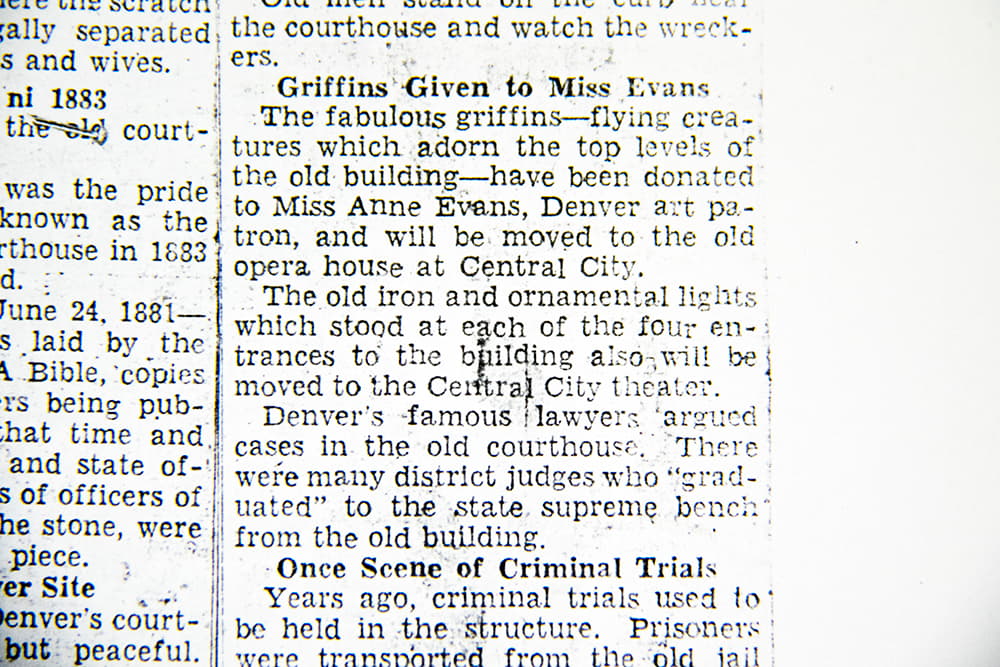

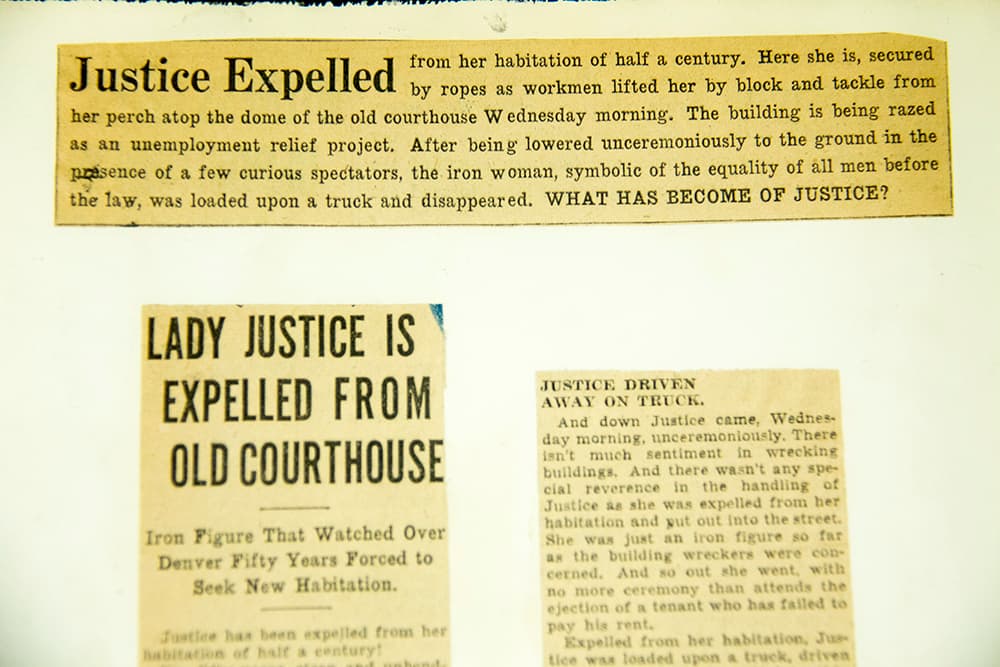

Some reports from the time suggested the city paid nothing for the building's demolition, instead offering the courthouse's raw materials to crews. Lady Justice was removed from atop the dome, where it was discovered she was made of "plain rusty tin" rather than bronze like everyone thought. The eight griffins were reportedly donated to Ann Evans, who moved them to the old Opera House in Central City (though nobody at the Byers Evans House nor the Central City Opera have ever heard of such a thing).

But the old courthouse's true controversy came in the end: what would happen to the downtown block that sat vacant for more than a decade? Hundreds of people began writing letters and protesting City Council when news broke in the '40s that the property might be sold for $750,000 to make way for a hotel or shopping center.

A testimony to City Council accused Mayor Stapleton of hiding the true nature of sales negotiations as a "dark secret." Indeed, it troubled people that several potential buyers hailed from New York City, outsiders from the growing western metropolis. Even when the sale went through, the Denver Post reported that "city officials claimed not to know the identity of the purchaser."

Groups like the Denver Women's Club publicly called for the space to become a park and asked that it house a memorial for soldiers lost in World War II.

What is perhaps another standard of this tradition played out as expected: commerce won, and the property was sold to a commercial entity. The block in question now is home to the Sheraton hotel.

"Proposed sale of the courthouse square was given its first vote of approval so quickly and quietly by the city council Monday evening that nearly 100 citizens who had appeared again to protest against the sale to an eastern firm did not realize what was happening,” the Denver Post reported on May 22, 1945.

Today, there are few who remain to lament the courthouse's decline or the loss of an open block west of Broadway. Instead, there's just one last Griffin for sale on the internet for a quarter million dollars.

As for Lon Stanley, the seller, he at least hopes someone with means comes along to buy the unique piece so it may be donated to the city for posterity. He would do it himself, he said, but he's spent too much of his own money on an antique addiction and he'd like to secure his own future first.