Early on in Republicans' efforts to overturn the Affordable Care Act, U.S. Sen. Cory Gardner joined three other Republican senators in states that had expanded Medicaid in calling on any replacement bill to preserve the expansion and the access to health care coverage it extended to millions of low-income Americans.

But since then, Gardner's name has been notably absent from the "will-he-or-won't-he" speculation that has swirled around each successive Republican bill, and he's voted in favor of every bill that has come to a floor vote -- often after weeks of saying he needed more information or hadn't made up his mind.

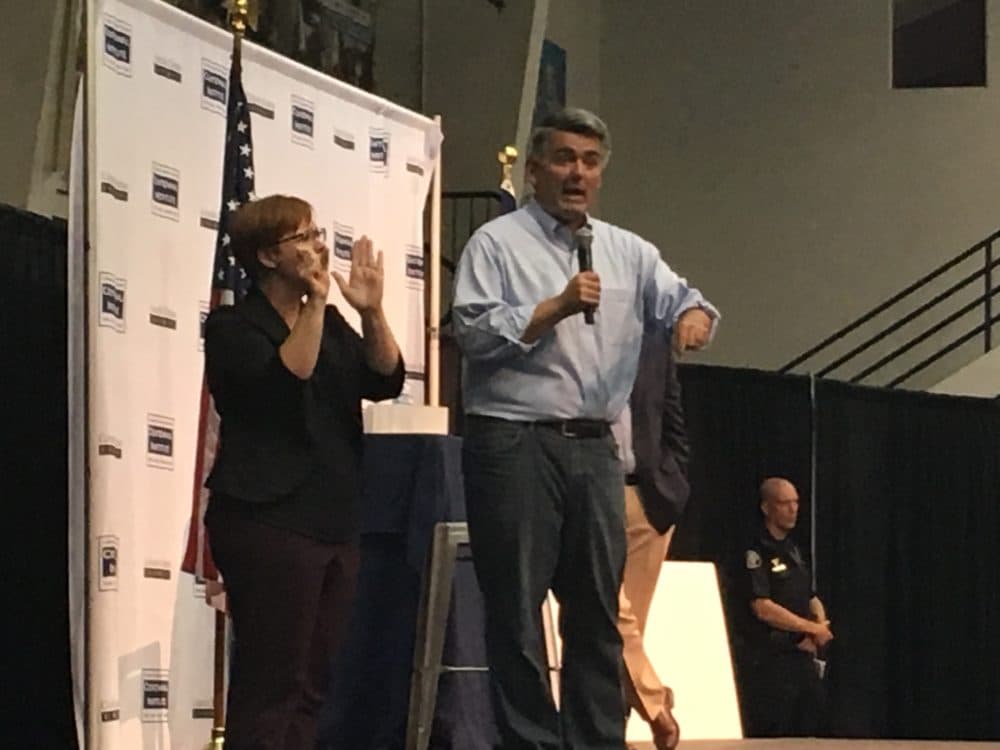

This pattern exists in an environment where progressive activists have made Gardner a relentless target of protests around health care. A New York Times story that appeared late last week provides more context for Gardner's position.

In addition to being the Republican senator from a politically divided state, Gardner is the chair of the National Republican Senatorial Committee, the group dedicated to electing Republican senators and strengthening their Senate majority (right now, three defections kill any bill that doesn't have Democratic support). It would be awkward to hold that position and vote against major Republican policy priorities, even if they are unpopular with voters. It also would put Gardner in a worse position as he tries to raise money for his colleagues.

The New York Times reports that in a closed-door meeting earlier this month, Gardner told Republican senators that "donors are furious" the party has not managed to pass any health care legislation. This is the "YOU HAD ONE JOB!" critique:

As more than 40 subdued Republican senators lunched on Chick-fil-A at a closed-door session last week, Senator Cory Gardner of Colorado painted a dire picture for his colleagues. Campaign fund-raising was drying up, he said, because of widespread disappointment among donors over the inability of the Republican Senate to repeal the Affordable Care Act or do much of anything else.

Mr. Gardner is in charge of his party’s midterm re-election push, and he warned that donors of all stripes were refusing to contribute another penny until the struggling majority produced some concrete results.

“Donors are furious,” one person knowledgeable about the private meeting quoted Mr. Gardner as saying. “We haven’t kept our promise.”

On Sunday, Gardner went on Face the Nation to say that health care reform is not about shoring up the base, appeasing donors or other political concerns.

Well, this has nothing to do with politics. It has nothing to do with donors. It has everything to do with the people of this country who are suffering each and every day under a health care bill that is failing to meet their needs, that's bankrupting them. I meet with countless people across the state of Colorado, all four corners here, who are basically paying a second mortgage every month to afford their insurance, to pay for their insurance that they can't actually afford to use.

There is no doubt that the health insurance market in rural Colorado needs a serious fix, but that leaves the question of whether Graham-Cassidy is legislation that would solve this problem.

The bill does away with the Medicaid expansion, on which rural Colorado is disproportionately dependent, as well as subsidies for private insurance that protect many low- and middle-income people from large premium increases. It replaces them with a grant program and a per-capita payment for Medicaid. It also would allow states to do away with consumer protections that prevent insurance companies from charging more to people with pre-existing conditions or that require insurance policies to cover certain procedures -- something most analysts think Colorado would be unlikely to allow.

The nonpartisan Colorado Health Institute has a summary of various analyses that have been done on the legislation, and Colorado loses significant federal funding under all of them -- with an expected loss in health care coverage to go with it.

According to the New York Times, despite the supposed fury of donors, Gardner did not explicitly tell his colleagues to vote yes on Graham-Cassidy, which is widely considered to be on its last legs as it has drawn opposition from both the right-wing of the Republican Party and more moderate members -- just like previous efforts.