Denver City Council voted 8-5 early Tuesday morning to create the city's newest historic district on 30 acres in West Highland known as Packard's Hill.

The testimony stretched almost four hours as nearly 90 people spoke in favor of and against the designation. By the numbers, those who actually lived in the district were close to evenly divided, and for those council members who voted no, that lack of community consensus weighed heavily upon them. They said the city's process for creating historic districts needs to change to better incorporate dissenting viewpoints and that the city in general -- and the residents of the Packard's Hill section of West Highland in particular -- should consider less restrictive preservation tools like conservation overlays.

Those who voted in favor said many historic designations have been strongly opposed, including the move to protect Lower Downtown -- only to appear as brilliant successes years later -- and that they have a higher accountability, not to just to the past, but to the future.

"Can you still build, expand and grow with historic designation? Yes. There is a clear desire within the community to preserve the character. ... We’re losing history at an alarming clip," said Councilman Rafael Espinoza, who represents the area.

Espinoza has been on the losing side of several battles to preserve individual properties in northwest Denver, where 80 percent of all demolition permits in the city are issued, and in those votes, his council colleagues said they would prefer to see a historic district rather than one-off designations.

Espinoza seemed caught off guard by the breadth of opposition to the historic district -- "I only have 11 emails in this entire time," he said at one point in response to a question from Council President Albus Brooks about what outreach he did to opponents of the designation -- and the meeting included dueling petitions and surveys that showed radically different numbers for support and opposition.

"I know that it is a gutsy vote, with the mix we seemingly have in this room, but we have 83 percent of the property owners not even here," Espinoza said. "That should also speak volumes. They’re just looking to us to follow this through."

Brooks, Espinoza and council members Jolon Clark, Paul Kashmann, Robin Kniech, Paul López, Wayne New and Debbie Ortega voted in favor of creating the district. Council members Kendra Black, Kevin Flynn, Stacie Gilmore, Chris Herndon and Mary Beth Susman voted against.

Herndon described an equally contentious historic designation process in Park Hill in his district. In that case, instead of bringing it to a vote, he facilitated a process of mediation that is ongoing. Residents for and against the historic district are discussing less restrictive ways to preserve the character of the neighborhood.

"Seeing neighborhoods get torn apart for this, it’s painful," he said, as he explained his no vote as one in support of process like the one Park Hill is following.

Several council members said the historic designation ordinance needs to be revisited because it favors the creation of districts rather than fulfilling the desires of a majority of residents.

But Kniech said that would be a mistake.

"The ordinance isn’t neutral," she said. "The ordinance is not about counting (support and opposition). It’s about what future generations will judge about what we’ve preserved in the city. That’s a higher accountability.

"I would not support changing this ordinance to be neutral because otherwise it serves no purpose."

The arguments for and against the district will be familiar to anyone who follows these things. Proponents want to protect the feel and character of the neighborhood from new development that feels out of place. They also just love beautiful, historic things and want them to stay around.

Chris Miles described how his great-grandfather settled in Packard's Hill after being fired by Buffalo Bill in a drunken rage (Buffalo Bill was the drunk one) and marveled that 82 percent of the homes in the area are the same ones that his great-grandfather would have known.

"We have a unique opportunity to preserve this neighborhood for generations to come," he said.

"Once they're gone, you never get them back," said Yvette Harrell, the owner of a distinct stone house in the neighborhood that is a landmark in its own right.

Opponents felt that the historic district would be an infringement on their property rights, in some cases making it hard for them to stay in the neighborhood.

Matthew Brown said he would turn his home into a rental and move out because the historic guidelines would make it too hard to expand his home to accommodate his young children.

Mark Brandes, an attorney who has restored a Victorian home that was once a boarding house and then a four-unit apartment building, said he values old architecture but doesn't believe people should have to jump through extra hoops to work on their homes. He called it a "slap in the face" to the people who moved into the neighborhood when it was rough "and contributed a lot to turning it around."

And Alex Holderness held himself up in contrast with longtime residents. He recently moved here from San Francisco and specifically bought a home in the area just for the lot.

"The entire reason that I moved into that home was so it could be scraped because my aesthetic does not align with what is allowed," he said.

With the historic designation, he won't be able to build the home he wants, he said.

Sharman Sather lives in the nearby Ghost Historic District, and she told opponents they might not be so angry in a few years.

"I was the naysayer. I was against it," she said. "I did not want an HOA telling me what to do in the home that I’ve lived in for 30 some years. I made it known to everybody, of course, that I was against it. Well, it passed, and I’m no longer against it.

"I don’t know where the contentiousness is. I still have friends. If this passes, which I hope it does, there will be a lot of people in hindsight who say, 'It’s not as bad as I thought it would be.' It hasn’t been."

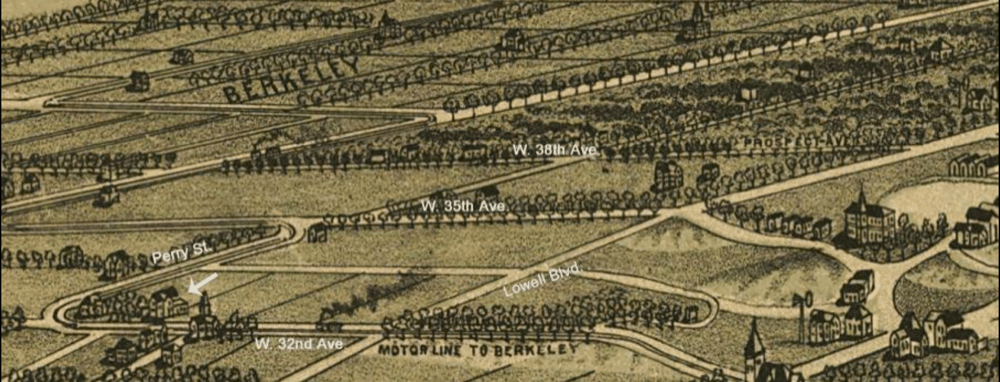

Packard’s Hill calls back to Denver's "first great period of growth" from 1880 through 1893, according to the application neighbors filed.

The neighborhood's name comes from William Carleton Packard who helped plat the area when it was still part of the former town of Highland. The oldest standing house in the community, 3825 W. 32nd Ave., dates back 131 years to 1886.

Over time, the neighborhood developed an eclectic mix of architectural styles, from stately Victorians and Queen Annes to more modest cottages and bungalows.

"Packard’s Hill is significant in strongly reflecting the influence of women in its development, property ownership, architecture and character. From its earliest period of development, women were investors and developers, buying and trading parcels of land in Packard’s Hill and/or participating in the construction and sale of houses," according to the application.

Notable women to live in the area include Dr. Mary E. Ford and Dr. Helene Byington, trailblazing female doctors; Eva Bird Bosworth, an area reporter and writer; Minnie Ethel Luke Keplinger, helped establish Denver's first art museum; and Spring Byington, a 1938 nominee for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in "You Can't Take It with You."

Two Denver mayors also lived in the area: Benjamin Stapleton and William Fitz Randolph Mills. As Senior City Planner Kara Hahn listed the ways in which Stapleton was significant to Denver, she ended with a mention of his involvement with the Ku Klux Klan, which sent a ripple of discomfort through the room.

Hours later, López could not hold back.

"I think it’s absolutely disgusting when we use Benjamin Stapleton as a historical reference," he said. "I don’t want to ever hear, 'Oh, we have to recognize this because of him.' It’s bad enough that we have a neighborhood named after him."

Denverite business and data reporter Adrian D. Garcia contributed to this report.