Tom Garcia was 13 years old when East Colfax Avenue became his home. He'd grown up inside homes for orphaned boys until a series of fights over a hot dog landed him and another boy in the hospital. When he got out, the young Garcia fled to Denver’s Colfax Avenue with pockets full of cash and jewelry stolen from his former roommates.

He would spend his teenage years in the 1970s causing mayhem in Capitol Hill and sleeping many nights on the street. He ran with a crew of street toughs, holding up strip clubs and luring drunken bar patrons into empty apartments to rob them.

“That was my area to destroy and conquer,” said Garcia, now in his sixties. "I destroyed those streets. Made them what they were. Turned it into a shithole."

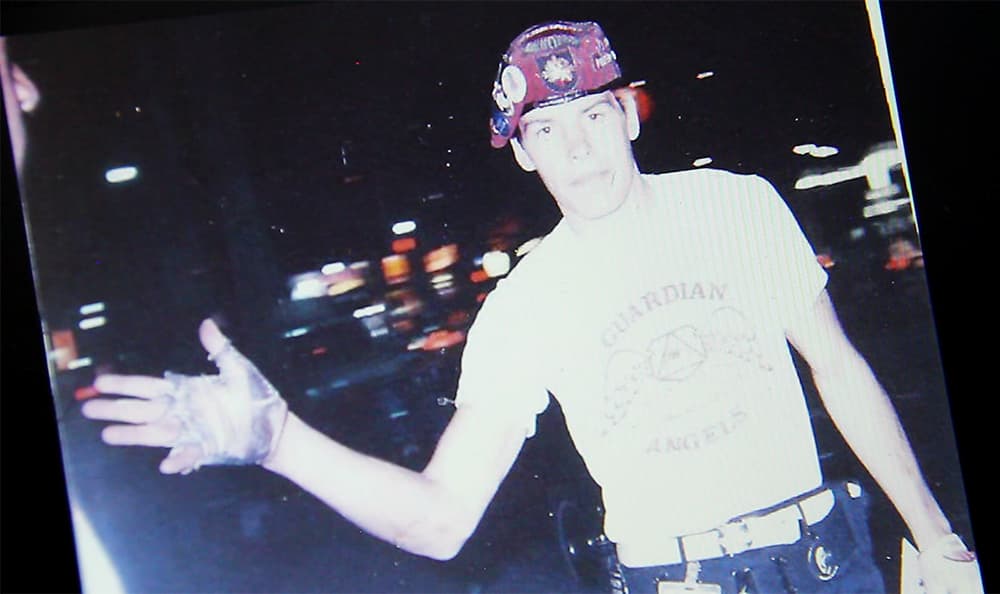

Garcia still frequents that East Colfax corridor, but with a far different mission. Today, he patrols the street in a red beret, combat boots and absolutely no weapons. He calls himself "Kukulkan," named for the feathered Mayan serpent. He is a Guardian Angel, the international group that took issues of street violence into its own hands.

The volunteer safety force has patrolled Capitol Hill since the early 90s, using their iconic paramilitary uniforms to stand out at "visual deterrents" to violence and breaking up the occasional drug deal. They're greeted by occasional jeers from speeding cars, smiles from people huddled beneath blankets and thanks from local business owners.

The Colorado Guardian Angels have watched Denver's most beloved and feared corridor for decades. Few know the drag as intimately as they do. Now, their numbers are dwindling and some ask whether their mission may be complete.

The Colorado Guardian Angels were born from a legacy of street violence.

David O'Shea-Dawkins worked much of his 35-year police career as an officer in Capitol Hill. He told Denverite that East Colfax has always attracted crime, but it was in the 1970s that urban renewal projects shook up central Denver and pushed crime and poverty into the East Colfax corridor.

"There was nobody really making decisions to make it a better place,” said Dawkins, who also grew up along the strip. "It was not a stable neighborhood."

Dawkins was a new recruit to the Colfax beat when Denver started shifting. As the city raged (and young Tom Garcia with it), other U.S. cities also wrestled with intensifying crime.

In New York, Curtis Sliwa decided he'd had enough of the violence in his neighborhood. Spurred to act, he founded the volunteer crime fighting group that became the Guardian Angels.

It wasn't until 1993 that things came to a head in Denver. A series of gang shootings dubbed the "summer of violence" sent the community into a panic. After a quadruple homicide at a Chuck E. Cheese's, a fierce debate about gun violence was stirred. As state senators argued whether handguns belonged in the formerly wild West, community groups in Denver decided to invite the Angels to town.

It wasn't long before the Colorado Guardian Angels were formed and settled into Capitol Hill.

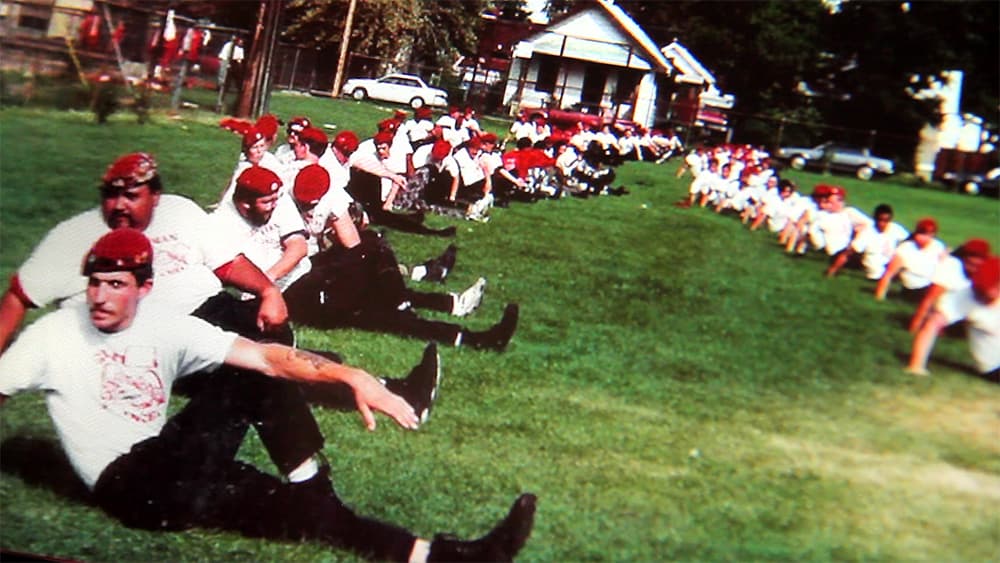

When the Angels called for recruits, nearly 200 volunteers showed up in Denver.

In 1993, one of Curtis Sliwa's right-hand men, Sebastian "Iron" Metz, was dispatched to Denver to scope out the city and start a chapter. Their first meeting filled a room at the Ramada Inn on Colfax and Downing. Among them was Robi Salo, who is now the chapter leader.

"We had heard quite a bit of controversy of the group," Salo said.

In their early years, the Angels were seen as vigilantes and came into conflict with New York authorities. But, he said, "it didn’t take long at all to convince me that this was a good thing to do." He soon took the call-sign "Wolf" and joined.

The fact that so many recruits showed up in Denver, Iron said, is "what made it attractive to us. It made the perfect recipe for positive change, because people were ready to do something."

From his recollection, Officer Dawkins said the Angels' arrival was welcomed by some cops and ignored by others. Dawkins said he saw them acting as "eyes and ears" for the police. He, for one, was fine with the help.

Their presence along Colfax seemed to have an effect.

During that first summer, Guardian Angels from all over the country arrived in Denver to run a three-month "military boot-camp," whipping recruits into shape with daily trainings and instilling their non-violent philosophy. They pushed out those who just wanted to crack skulls, began patrols and set up a headquarters on Pearl Street at 14th Avenue.

In those days, Wolf said, building owners welcomed the Angels into their blighted properties. The basement apartment on Pearl Street, now a fairly high-end building in a bustling neighborhood, was derelict when Wolf and his comrades established their headquarters there. He described it as a "crack house."

Apparently, some didn't appreciate this new uniformed presence. His truck was covered in spray paint their first night on patrol. But, he said, “it ignited me."

As the Angels settled at the Pearl Street apartments, Wolf said, they saw the drug and sex trade shrink from the street and the building.

That Pearl Street location became too nice for the Angels, Wolf joked. Each time they'd clean up a block, they'd also seem to find themselves out of an HQ.

On patrol, the Angels tell stories.

Wolf talks proudly about busting drug deals, pulling sex workers and their clients off of street corners, breaking up street brawls and chasing down thieves.

They've acted as private security for the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Marade since its founding in the mid-90s. In its early years, when white supremacists attempted to get their event permit, Angels camped out in the snow to save their spot in line.

They take pride in the wellness checks they perform for people sleeping outside on frozen nights and say they've saved a number of lives.

One frigid New Year's Eve, Wolf said, he saw a hit-and-run across Colfax from the Sun Cafe (now Tom's Diner) in which a drunk driver crushed a woman in the parking lot and then sped away.

As the car twisted her body, he said, "you could hear bones breaking.” When it bolted from the scene, Wolf remembers sprinting after the car with the speed that earned him his nickname. He managed to ID the driver when police arrived. He testified in the driver's trial months later; the woman was still in a wheelchair.

The Angels were once an international phenomenon.

In the '90s, support was strong and in Denver you might have seen 10 or more in uniform and on patrol every night of the week.

Sally "Apache" Martinez, who's been with the Angels since the start, said things were so busy and exciting that she quit her corporate job to move into headquarters full-time. They started running programs with other neighborhoods and even tried out a roller blade patrol.

As Iron's assistant for 14 years, Apache held the group together and traveled the world on Angels business.

In 2005, Iron had a series of near-death health episodes that perhaps slowed the chapter for good. As things winded down, Apache retired. She met Tom and married him.

By then he'd survived a few close calls and had decided to play it straight. His life came to a halt when his son was killed in a botched robbery. Looking for a positive outlet to pour himself into, Garcia became Kukulkan with the Angels.

Today, the two of them still show up for patrols, but things are slower than they used be. Patrols are down to once a week and attendance has dropped. But there's also no longer as much for the Angels to do as there used to be. The neighborhood has changed around them.

Walking the blocks with them, you get the sense that what the Angels appreciate most is an opportunity to serve the neighborhood. It's a chance to participate in Denver's civic life, to be seen on the street and to work toward something positive. Even if few people recognize the uniforms these days, it binds them together and gives them purpose.

"It’s our community, it’s our neighborhoods," Wolf told me in an interview at his home. "If all of us individually do a little bit of something, this world would be a far better place," he said. "That’s what drives me."

He told me he suffered PTSD after he was present at Columbine High School during the 1999 massacre. While working a handyman job nearby, he heard shots and ran on campus to find students covered in blood. He rushed in to act -- a result of his Angels training -- but ran into an undercover police officer who held him at gunpoint in the chaos.

Later, he visited a minister and asked why he so often came so close to death and violence.

"It wasn’t the burden God gave me to carry," Wolf remembered the minister told him. "It was the gift."

Like Wolf, Kukulkan's dedication to the Angels runs deep. He sees an opportunity to erase the legacy he left on the street, a channel for redemption.

"I've never wanted to be a cop, never once ever," Tom said.

"But I do want to be out there protecting people on the streets that I created. It’s meaningful, it gives me purpose in my life, makes me feel good about myself, and I think my children and my family look at me differently -- they look at me as a leader."