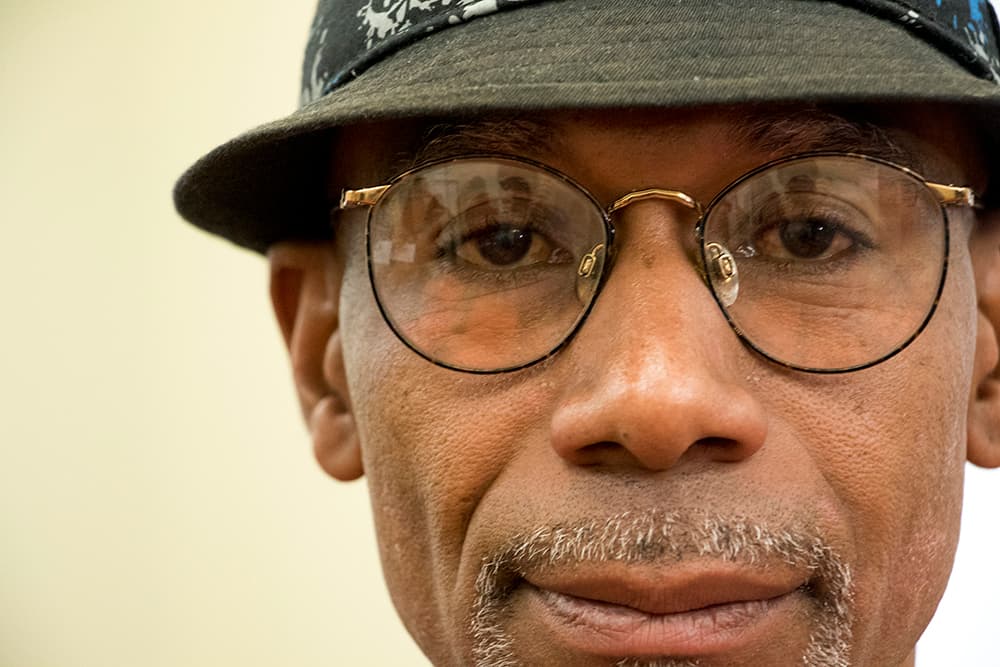

Maurice Cushinberry, 50, got a life-changing surprise when he walked into the office of a social service provider earlier this year.

There was a message waiting for him. He didn't know it then, but he was going to be one of the first subjects in an ambitious experiment. Someone he had never met wanted to find him a place to live.

"I thought they were full of it," he recalled today.

Cushinberry couldn't imagine that anyone would be looking for him, at least not for any good reason. He had been homeless for nearly two years, circulating between friend's couches, shelters and jails. His recent record included jail time related to alcohol and substances, as well as a violation of a park curfew -- not unusual for someone living outside.

"I hadn't even bothered," he said of the idea of finding housing. "I knew it was a long list."

Usually, a criminal record hurts the housing search. Instead, Cushinberry is one of about 200 people in Denver who have been placed in housing specifically because they have spent time in jail. They are subjects in an $8.7 million experiment that may be the first of its scale in the United States.

Soon enough, Cushinberry had the keys to a condominium near Buckley Air Force Base. Hundreds more people will be placed through the same program in new apartment buildings off Federal and off Broadway.

The question is simple: Can housing and services keep people off the streets and out of jails?

The administrators of the new program began last year by combing through police records. They were looking for people experiencing homelessness who had frequent stretches in jail for low-level crimes such as public urination or failing to appear in court.

Roughly 2,000 people might fit the definition in Denver, but the new effort began by selecting just 100 people, mostly middle-aged men. On average, they had been jailed about five times per year.

The idea is that local government is spending money to arrest people experiencing homelessness and keep them in jail, but simply housing them may be less expensive and more likely to break the cycle.

“They’re looking at, ‘Do the costs go down when you house people?’ We have always found that that’s true,” said Cathy Alderman, a spokeswoman for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, a key player in the program, along with the city and the Mental Health Center of Denver.

“Once someone’s stably housed, they may access more health care up front. They eventually stabilize and get into more regular routines.”

What were the results?

Denver and its partners are just 18 months into this five-year experiment, but city officials say the early signs are promising.

Out of 100 people selected for the first wave, staffers were able to find and house 66 people. Some were placed in condos or apartments scattered around the city, but most will live in new apartments built with this program in mind. They pay up to 30 percent of their income -- which is often zero -- for rent.

Once they're in housing, each person is paired with a team of about 10 professionals, including a psychiatrist, a nurse and a case manager -- the kind of "wraparound" services that the federal government largely stopped funding in the early 2000s.

The majority of early participants have stuck with the program. Of those who signed leases in the first six months, 33 people had maintained housing for a full year, and only one had left the program. Six had died, a sad sign of the health problems that come with chronic homelessness. (Not all participants have been in the program for a full year on June 30, when the analysis was done, which is why these numbers don't account for everyone.)

It's too early to say conclusively whether housing will keep the program participants out of jail, but the early indications are that it's relatively rare for those who stay housed to end up in jail.

On average, local people who meet the program criteria might spend 77 days per year in Denver jails, according to preliminary research. That number was just eight days among the people who have been with the program for more than a year.

Further reports in the years ahead will go into much more detail about the program's effects on jail time. That analysis is being done by the Urban Institute, described as an independent evaluator, as part of a study that will last five years in all.

"They're doing the most rigorous and longest evaluation of a supportive housing project in the country," said Tyler Jaeckel, the project lead for the city of Denver and the program director for Harvard's Government Performance Lab.

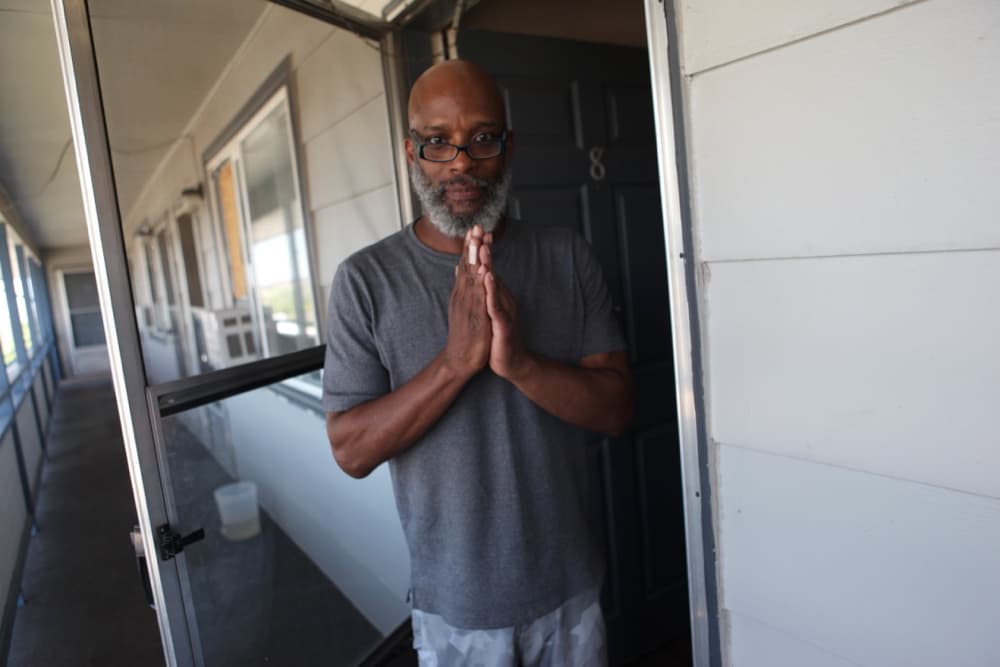

One participant, Reggie, had been to the hospital more times than he could count for injuries sustained in fights and from a lifetime of hard work.

His place was immaculate when I visited this summer, and he was working on meeting the criteria for his hip replacement surgery: no drinking, no smoking. He looked back on dark days and saw something different ahead.

“I’m not a part of the environment, so to speak, that’s out there with the filth and the muck and the scum and everything else they throw at you,” he said. “I didn’t need a program. I needed a place to stay, or I’d be dead or in jail.”

Who's paying for this?

The answer is more interesting than you might expect. About $8.7 million comes from "social impact" bonds provided by a long list of big-name investors and nonprofits, including such local presences as The Denver Foundation, The Piton Foundation, Northern Trust and the Colorado Health Foundation.

The city will repay that money based on estimated savings in jail and court costs. The first payment totaled about $188,000. If the program isn't working -- and participants do end up back in jail or lose their housing -- the city will pay less to the investors because it's spending more on jail costs.

The city's payments are capped at $11.42 million, a $3 million profit for investors, but investors aren't guaranteed to make anything. The payment system gives an incentive to rigorously measure the program's results.

"And from a government’s perspective, what’s really great about it is, I’m really only paying for a successful program," Jaeckel said.

Based on previous studies, the city hopes to see 83 percent of participants maintain their housing and a 35 to 40 percent reduction in jail days. That would yield a payment of $9.5 million.

The city estimates that it costs society about $29,000 per year to pay for jail, court and medical expenses for a person experiencing homelessness. This program costs about $22,000 per person for services, Jaeckel said.

In the end, this project might not prove that supportive housing is financially cheaper than jail -- but that's not the goal. The goal is to prove what it might cost to provide more productive and ethical options than incarceration.

If it works, this model could be expanded to other groups of people.

"We have another cohort that may not ever touch the jails," said John Parvensky, President of the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. "They're cycling in and out of our emergency departments."

As for Cushinberry, he's looking sharp these days in a blue-striped fedora and a dark-knit sweater. He's had no run-ins with police since he got his new place, and he's looking for new work.

"If all my neighbors knew my past," he said,"they might not have wanted me in the area."

But they don't know, so he's giving himself another shot, exploring the bike paths that run near his new home and adapting again to life inside.