One of the problems presented by the name Stapleton is that you can't unknow something.

Lots of people who moved to this community in northeast Denver -- those who moved from elsewhere and even those who grew up here -- bought homes without knowing much about man for whom the old airport was named.

Now that the Klan allegiances of five-term Denver Mayor Benjamin Stapleton are much more common knowledge, what are we saying when we say the community should keep his name?

"It's not just a name we need to give a different meaning to," Mandle Rousseau said Monday at a facilitated conversation on the use of the name. "The airport was named for someone."

Rousseau said he grew up in Denver but didn't know much about Stapleton the man when he moved to the neighborhood a year ago. As a black man, he spent time thinking about the implications for him, particularly in an era when demographic trends see Denver getting whiter.

"This might be a small thing compared to other things going on in this country, but if you know something is wrong, you change it," he said.

It's not that simple for everyone. Justin Ross, who is also black, moved to Stapleton in 2002 and lived on a block where the majority of residents were racial or ethnic minorities. He's heavily involved in the community, serving as president of the Greater Stapleton Business Association and sitting on the Housing and Diversity sub-committee of Stapleton's Citizens Advisory Board, a body that presses Forest City to fulfill its promises to build an economically and racially diverse community.

Ross also uses Stapleton in his business name and isn't keen to rebrand after more than a decade.

"I don't necessarily think the name change poses the impact that I'd like to see," he said. "I would like to see more black and brown families welcome here. I do not like to see posts on Nextdoor saying someone looks like they don't belong here. If I could be convinced that a name change would make us more welcoming, I would be all for it."

Supporters of the name change appeared to be a majority at the facilitated discussions.

Roughly 130 people attended two separate facilitated discussions in Stapleton Monday to share their views on changing the name of the community. There's no good way to know how representative their views are of the broader community, and whether this is the type of decision that should be made by majority rule is an entirely different question.

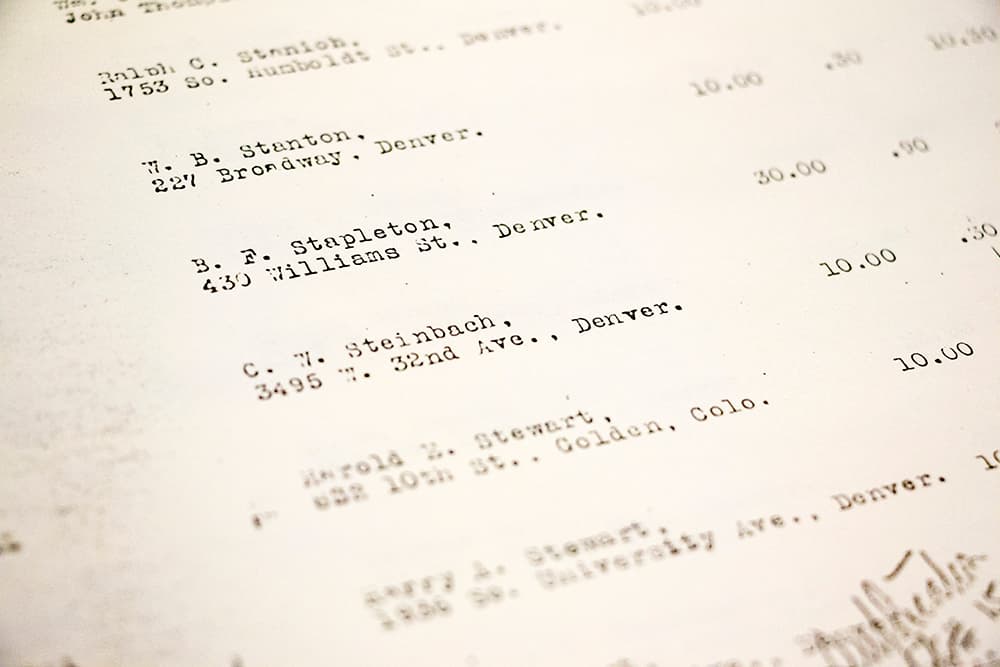

Benjamin Stapleton hid his Klan allegiances when he first ran for mayor in 1923, but he filled city government, particularly the police department, with Klan members and relied on them to survive a recall effort launched by disillusioned supporters. Later, Stapleton tired of Klan efforts to control him, distanced himself personally from the organization and used Catholic police officers to root out corrupt Klan officers. By 1925, Stapleton was welcoming the NAACP national convention to Denver, but his break with the Klan was not clean and simple.

Stapleton was also known as Builder Ben and built the first Denver Municipal Airport, along with the City and County Building, I-25 and Red Rocks Amphitheater. The airport was later named for him, and that's where the community on the old airport site gets its name.

People who want to keep the name often speak about "reclaiming" it or "redeeming" it.

Jessica Ostermick, a former board member of the Master Community Association, said changing the name would send a message but actively pursuing a message of inclusivity under the name would send a stronger one.

"If you took the Stapleton name and said, 'This is who we are as a community,' through art projects, through financial donations, through other projects, that would send an even more incredible message," she said. "When you take a name and wipe it clean, you lose the opportunity to make it mean something wonderful and beautiful and the complete opposite of what he stood for."

Michael Hesse said that as Catholics, his grandparents would have been targeted by the Klan, but his religion also teaches forgiveness.

"Being Catholic, I believe people need to be judged by their whole lives," he said, citing Stapleton's expansion of the parks system and the fact that the people of Denver re-elected him repeatedly. "We need to look at his full record before deciding he is irredeemable."

Everyone who talked about redemption or asked that Stapleton's Klan membership not be his defining legacy was white. One man said he "empathized" with Stapleton as someone who grew up in a racist household and had to unlearn bigotry. There are people of color who don't want to change the name, but none of them talked about redemption.

And Ron Adams rejected the idea that white privilege or institutional racism has anything to do with why Stapleton is 83 percent white, whiter not only than the surrounding Denver neighborhoods but whiter than the city as a whole or the state as a whole.

"Stapleton is a meritocracy," he said. "You work hard, you earn the money, you can live where you want."

To applause from some in the audience, Adams said Stapleton had to be part of the Klan to destroy it "and that's what he did."

Those who want to change the name don't see anything to redeem.

A highway project, an amphitheater, an airport, these may be good things but they don't make up for facilitating a reign of terror, they said. While Stapleton distanced himself from the Klan, there's not much evidence he condemned them. Historian Phil Goodstein describes the Klan as going out of fashion due to corruption and incompetence rather than being boldly rejected in Denver.

"Nobody is saying, 'redeem Hitler,'" said Lisa Calderón of the Colorado Latino Forum. "I'm not comparing Ben Stapleton to Hitler, but I am comparing the Klan to genocidal terrorists."

The name change discussion is tied up with deep questions about community in Stapleton. There are people who don't feel that it's as open and accepting as it purports to be, and there is frustration that Forest City hasn't met its affordable housing commitments.

Aisha Rousseau, Mandle Rousseau's wife, described being mistaken for a maid when she first moved into her home. Dipti Nevrekar said classmates have called her dark-skinned son by racial slurs and have said they are glad their skin isn't the color of his.

Not all non-white Stapleton residents share these experiences. Rajeev Vibhakar said he feels there's more inclusivity in Stapleton than large cities he's lived in, and he doesn't want that to get lost in the name change debate, about which he doesn't have a strong opinion.

But Brooke Lee said recent experiences give the name unfortunate resonance. She grew up in San Francisco and lived in Oakland before moving to Denver and to Stapleton. A sense of safety was one of the things that attracted her to the neighborhood, but she doesn't feel safe anymore. A neighbor saw a white man harassing Spanish-speaking nannies at the park, screaming at them that this was an English-only neighborhood. Later, another white man followed home a Korean-American family and screamed at them that they didn't belong there.

"How do I feel safe when I have to carry that vigilance with me?" said Lee, who is Asian-American. "What does it tell that man if we don't change the name? If it's just too much trouble? If we just don't care enough? I think it tells him that all my neighbors secretly agree with me."

There isn't just one place where the name could be changed.

There's the registered neighborhood organization, there's the Master Community Association, there's Forest City's marketing and signage, there's the use the city makes of it in describing the statistical neighborhood.

Each of these would require a different process for changing the name -- and in some cases, the process isn't defined.

Alisha Brown, vice president of the Stapleton Foundation, which hosted the conversation, said the foundation will help distribute the feedback to all the relevant groups. Brown also will take the feedback to the board of the Stapleton Foundation, which takes its name from the airport. The first iteration of the foundation created the redevelopment plan and ushered it through the city process; the organization now focuses on issues of social equity within Stapleton, including supporting wellness and transportation programs. (If Forest City is responsible for the "bricks and mortar," the Stapleton Foundation is responsible for the "heart and soul," Brown said.

Later this month, the Citizens Advisory Board will take a vote on whether the name should change. The result of that vote will form a recommendation for Stapleton Development Corporation.

"No matter which side of this fight you fall on, do something meaningful," urged Jim Wagenlander, co-chair of the advisory board.

Jackie St. John, a member of Rename St*pleton for All, said the best opportunity to redeem the name Stapleton is to change it.

"It might turn out that the name Stapleton means, 'That's the place where we turned around and looked at ourselves,'" she said.